WONDER WOMAN

The Epiphanies of Annie Dillard

by Simon Schreyer

xx

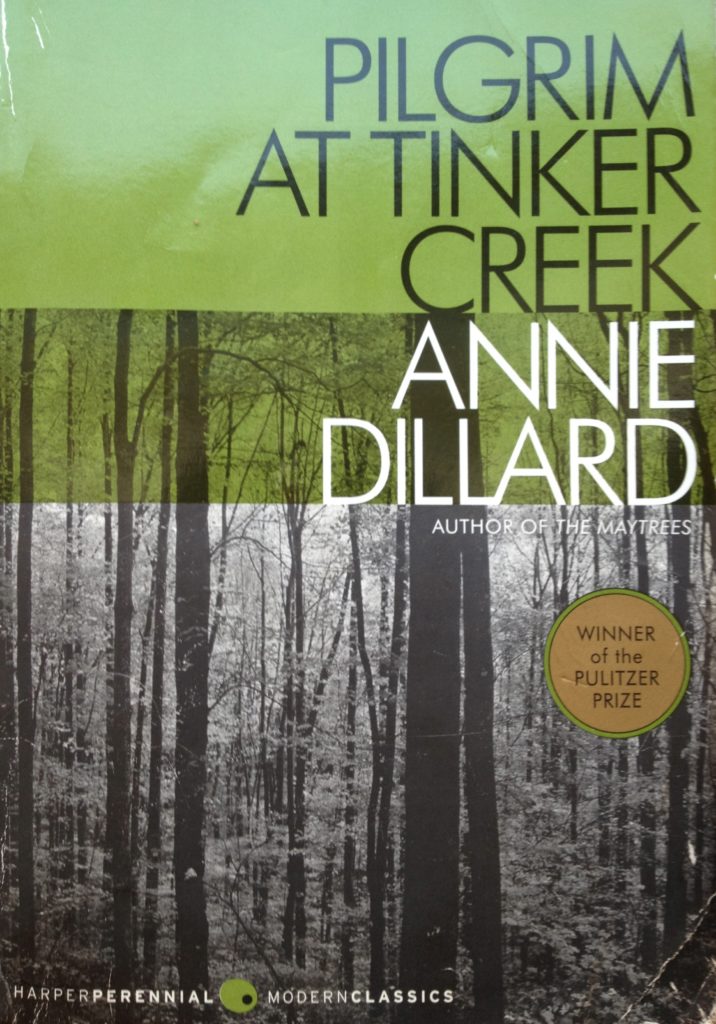

In the writing of Annie Dillard, Mother Earth is an almighty force and quite a quirky lady. In books like Pilgrim at Tinker Creek and Teaching a Stone to Talk, Dillard takes her readers into the natural world, describing its divinity and fascination, as well as its often bizarre cruelty. She also reveals her sense of bewilderment and wide-eyed wonder in a transcendentalist manner all her own.

xx

“In the minds of geniuses, we find – once more – our own neglected thoughts.”

– Ralph Waldo Emerson

xx

x

xxx

Sea lions playing on the lava boulders of the Galápagos islands. Connecting with the mind of a weasel. Baby frogs being sucked out from the inside by wicked water bugs. The history of sand. The racing shadow of an awe-inspiring solar eclipse. Going to Disneyland with Allen Ginsberg and Chinese writers. Coaxing a smooth, round stone into communication. Setting out from these topical areas, it is easy to guess who the writer in question would be if this was a quiz. Of course, we are talking about Annie Dillard, a national (and natural) treasure of the USA.

Hardly any other female nature writer has had such an impact on the American literary scene as Annie Dillard, with the possible exception of her sister in spirit, Gretel Ehrlich, and, perhaps, Joan Didion. In comparison to Ehrlich, who has had a few flashing encounters with the bare forces of the elements, as she was struck by lightning twice and lived to tell the tale, Dillard was almost spoiled by destiny. Yet she keeps a sharp, ruthless eye on the abundant forces of creation and inspects, in great detail, the gifts of the universe.

xx

✺

xx

Born to a well-off family in Pittsburgh, just after World War II, Annie Dillard was of the first generation of women, who were free to choose her vessel to float down the river of life. From an early age, as she writes in An American Childhood (1987), she was gifted with an independent, curious spirit: “My mother had given me the freedom of the streets as soon as I could say our telephone number.”

Also from an early age, she was fascinated by the flowing element; ponds, lakes, streams, beaches, and creeks feature greatly in her books.

We can imagine the girlish Annie bogged down over a puddle, stunned into stillness and concentration, trying to save an oscillating green bug from its murk with a stick to bring it home, and in a way, this sort of endeavor, digging in the dirt for small shells and small shocks, has become her occupation and her claim to fame ever after.

Initially religious, she quit attending the Presbyterian church as a teenager “for its hypocrisy” and later marveled about Christian doctrines, some of which she would go on to describe as “absurd”. However, she remained socially engaged, took part throughout her college years, in the Anti-Poverty program, and learned about Judaism, Islam, Buddhism, and Inuit religions. In the late 1980s, she even turned towards Roman Catholicism for a while, only to “stay near Christianity” after this spiritual fling – mainly for her reverence towards the noble-minded French priest and writer Pierre Teilhard de Chardin.

Why am I mentioning religion? Because the unfathomable complexity of creation seems to be at the core of Annie Dillard’s books. She is a soul searcher, a pilgrim in the natural world. She wants contact with the divine. She needs explanations. Don’t we all?

But rare are those among us who retreat to a house in the wilderness to keep the senses heightened with caffeine and to venture daily to find microscopic and macroscopic miracles on the banks of a stream somewhere in the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia.

In 1974, Annie Dillard did just that, following in the footsteps of Henry David Thoreau (the subject of her master’s thesis), and writing about it. In 1975, at barely thirty, she won the Pulitzer Prize in the Non-Fiction category for Pilgrim at Tinker Creek.

Tinker Creek, like its literary precursor Walden, is a classic of American Non-Fiction, a book that is part of the canon of works that high school students are obliged to read (a deplorable destiny for a book, according to its author).

On the other hand: Who can resist reading a book that begins like this? “I used to have a cat, an old fighting tom, who would jump through the open window by my bed in the middle of the night and land on my chest. I’d half awaken. He’d stick his skull under my nose and purr, stinking of urine and blood. Some nights he kneaded my bare chest with his front paws, powerfully, arching his back, as if sharpening his claws, or pummeling a mother for milk. And some mornings I’d wake in daylight to find my body covered with paw prints in blood; I looked as if I’d been painted with roses.”

Just this one opening paragraph says so much about Annie Dillard’s work: Here she is describing a scene as mundane as it is nightmarishly demonic and subliminally sexual like a Fuseli painting, employing a language that is unembellished in a carefree way, almost colloquial. You’d bet she is fun to hang out with, as you would imagine Jennifer Lawrence to be fun to hang out with.

She also uses the anatomical “skull”, not the more familiar “head”, and she brings together two images tightly connected with the female: Blood and Roses. The messenger of these images, though, is a tomcat – a Mercury of nocturnal wilderness, an envoy of lust and carnage. He doesn’t know what it is he is delivering from the outside; he holds no remorse, no bad conscience concerning his wild mating or the doom he brought upon mice or birds. Welcome to a day in the life of Annie Dillard.

xx

©walltowall Quotes

When Annie Dillard is on top of her game, she is herself a messenger of the sublime. Her game is the field research into the apparently mindless clockwork that is nature, in which everything and everyone is but a small cog in an organic machine as large as the cosmos.

Our existence, blissful, frightening, occasionally overwhelming as it may be, is so only to us human busybodies: “No use running to tell anyone. Significant as it is, it does not matter a whit. For what is significance? It is significant for people. No people, no significance. This is all I have to tell you,” Dillard writes in Total Eclipse, a hair-raising account of an excursion to witness a total eclipse, a short story (?)/essay (?)/piece of reportage (?) that was included in the compilation Best American Essays of the Century (2000) and will make any reader’s heart screech: “The second before the sun went out we saw a wall of black shadow come speeding at us. We no sooner saw it than it was upon us, like thunder. It roared up the valley. It knocked us out. (…) It rolled at you across the land at 1,800 miles an hour, hauling darkness like plague behind it.”

No wonder an early critic of her work called her “one of the foremost horror writers of the 20th century.” But then, she only describes what she sees. It is God who came up with the plot.

xx

© Shadowland

xxx

Annie Dillard’s third book (her first publication, in 1974, had been a collection of poetry, Tickets for a Prayer Wheel) was written not by a creek but between the expanse of the Puget Sound and the high-rising Rockies. As the surrounding landscape became more majestic, her writing became more refined and sparse. Holy the Firm, published in 1977, consists of only 66 rather short pages that took her 14 months to complete.

The book’s central, most illuminating passage is that of a moth getting caught in Dillard’s camping candle. As the expired insect’s body feeds the flame, it undergoes a metamorphosis and turns into the prototypical image of the poète maudit, sacrificing his burning soul for the arts: “The moth’s head was fire. She burned for two hours… like a hollow saint, like a flame-faced virgin gone to God, while I read by her light, kindled, while Rimbaud in Paris burnt out his brains in a thousand poems.”

xx

✺

xx

xx

With a diamond-mind like Annie Dillard’s, inspiration seems ever-present. But as it turns out, she is also a craftswoman with close connections to the academic world; she was married to a professor, R. H. W. Dillard, who was eight years her senior and whose name she kept. She also must have kept close contact with earth-bound editors and critics throughout her career, even as she had both eyes turned towards the perennial.

xx

xx

In her biography cum writer’s manual The Writing Life (1989), she advises writers to let it all out right here, right now, and not keep anything for later, because, there might be no later: “Spend it all, shoot it, play it, lose it, all, right away, every time. (…) The impulse to save something good for a better place later is the signal to spend it now. Something more will arise for later, something better. These things fill from behind, from beneath, like well water. Similarly, the impulse to keep to yourself what you have learned is not only shameful, it is destructive. Anything you do not give freely and abundantly becomes lost to you. You open your safe and find ashes.”

And about the ideal working place: “One wants a room with no view, so imagination can meet memory in the dark.” One may add: And so the moth’s head can burn brightly through the night.

As these scribbles take shape, a news story makes its rounds among the network outlets of the media world about a young man, named Sam, who was attacked by an army of minuscule sea lice on the sandy shore of Australia. The meat-loving critters’ bites were tiny and the water cold, so he didn’t notice his feet were bleeding so profusely that he had to be taken to the hospital. The appetite that this small species of crab is showing is completely new to marine science. Now, that is a story that surely would attract the attention of one Annie Dillard, if it hasn’t already. Not that the world is waiting for The Revenge of the Amazing Live Sea-Monkeys, but the idea of usually family-friendly, crustaceans (“eager-to-please” as the advertisement went) turning into a cloud of voracious carnivores would have her on her toes for sure, but then again: Does Annie Dillard care at all about current events?

xx

“We are here on the planet only once, and might as well get a feel for the place.”

xx

Seeing and reporting the machinations of the natural world (of which we are part, even if we think we are not, with our Netflix accounts, downtown offices, frequent flyer miles, and takeaway meals) can have an air of bluntness, even cruelness about it – a cold matter-of-fact tone and hard-boiled outlook on existence that some writers have integrated into their persona and their oeuvre: Hemingway employed it to its professional use since he learned to be an impassionate, manly reporter and eventually succumbed to it because he was a passionate, soft man at heart. Burroughs enjoyed it because it was anti-bourgeois, but mainly because it matched the temperature of his chilled bloodstream. Agatha Christie was ostentatious in not giving in to sentimentalism about human nature, and neither was Virginia Woolf. Nabokov operated with it and exhibited his characters like a satin-upholstered Aurelian board of prepared butterflies.

© Sergey Ryhzkov

Dillard, as a nature writer, has this impassioned regard as well, but she is startled by it herself (read for example her short story The Deer at Providencia), just like she is startled by the weirdnesses of the wildernesses in which she wanders and wonders, and often she conveys her troubling observations in confidential complicity to us. Just as if she wanted to fathom the disgust it might invoke in the reader. Then she retreats into her prolific soliloquy of slightly autistic splendor that is hardly ever shared by another character in her books: there is almost no dialogue in Annie Dillard’s work at all.

As a welcome mental balance, however, she also has a wide-eyed vulnerability, a childlike openness (not to be confused with naivety) that might be taken as a cunning self-staging, mostly by bitter cerebral men, jealous of her literary success. A situation not unlike the one surrounding the Austrian poet Ingeborg Bachmann about whom the German writer Walter Kempowski said: “She too, has this women’s quirk of behaving like she just fell out of the blue sky.”

xx

Reading Annie Dillard, one does get the impression that she indeed just fell out of the blue sky. She describes herself as “friendly and pleasant, but easily distracted”. At times one wonders how she didn’t accidentally burn down her Tinker Creek cabin or how grown-ups would entrust their teenage daughter to her care (Aces and Eights), but then again: Maybe the real Annie Dillard is completely different from the floating vessel of perceptiveness that is her narrative self? I certainly do not know.

According to the ever wickedly charming Geoff Dyer (the novelist and essayist, not the FT’s China correspondent), she is “pretty much a fruitcake”. Which, at least, makes her more colorful, more generous, sweeter, and softer than if he had said that she was a nutcase. Global soul Pico Iyer, who had the chance to play ping pong with her, describes her as “flamingly vital, (…), unpredictable as a whirlwind”, and “completely different from the person we meet on the page”.

xx

©Raymond Meeks

xx

xx

At a recent awards ceremony, as she was honored with a National Medal of the Arts and Humanities in September 2015, President Obama was visibly thrilled by her presence and after gallantly swirling her out of a little jig she was beginning to dance with him on the podium, held Dillard close to him so she would not fly out of a White House window.

But that is just what true artists do. They fly out of windows. And if they, and we, are lucky, they bring it all back home – out of the blue. Richard Buckminster Fuller, the architect of the geodesic dome and theorist of the “Spaceship Earth” compared her prose to the silver-streaking arches of the flying fish and in The New York Times, critic Eudora Welty called Annie Dillard’s writing “admirable” and “revealing a sense of wonder, fearless and unbridled”, combined with an “intensity of experience that she seems to live in order to declare,” but “I honestly don’t know what she is talking about at times.”

Sometimes I don’t know either, but very often Annie Dillard hits on all six and gets her point across as sharply as the very beaks and claws of nature she describes, and her sentiments are defined so sprucely that the quality of these often gleefully dark observations and epiphanies are akin to what Zen monks call a Sartori – a flash of subconscious recognition.

Occasionally, I start reading one of her pieces tentatively, with an eerie feeling of foreboding of what might be coming, and only awake at the last line, in a state of delicious, disquieted reverie, even comfortably mild trauma. Like when she finds the golden Guernsey cow lying gently on its side on a clear piece of land only to discover when walking around it, that the cow is hollowed out by death and decay, “dry leather on a frame, like a kettle drum. Her mouth was open and there was nothing in it but teeth. Instead of the roof of her mouth, I saw the dry pan of her skull.”

©Harper

Or when she ran from Santa as a child because thinking “like everyone in his right mind”, that Santa was God and knew when a child had been good or bad, and she had been bad: “Santa Claus stood in the doorway with night over his shoulder, letting in all the cold air of the sky; Santa Claus stood in the doorway monstrous and bright, powerless, ringing a loud bell and repeating Merry Christmas, Merry Christmas. I never came down. I don’t know who ate the cookies.”

About a trip to the Amazon, she writes: “The children would sing in piping Spanish, high-pitched and pure; they would sing Nearer My God to Thee in Quechua, very fast. To reciprocate, we sang for them Old MacDonald Has a Farm; I thought they might recognize the animal sounds. Of course, they thought we were out of our minds.” (from In the Jungle)

Or, from the haunting rural miniature A Field of Silence: “(…) The rooster, reptilian, kept one alert and alien eye on me. (…) Behind the rooster, suddenly, I saw the silence heaped on the fields like trays.”

xx

xx

©R.Kent

xx

At times her literary sketches and watercolors of the soul (she doesn’t do oil though) remind me of the glowing, airily composed paintings of another American naturalist with an enkindled eye, the landscape artist and designer Rockwell Kent, with his wide and frozen Patagonian spaces, his portraits of grumpy Inuits, his painting of a woman immersed in the privacy of a book with the immense plain of the ocean right behind her. Or his perfect rock shapes under a starry galaxy, working in ways eternally mysterious to us, while we can only marvel at its beauty – until rigor mortis sets in, or murderous scampi come to fetch us.

“The mind wants to live forever, or wants to learn a very good reason why not”, Annie Dillard ponders in Teaching a Stone To Talk, and (Zadie Smith must surely love this): “The mind wants the world to return its love or its awareness; the mind wants to know all the world, and all eternity, and God. The mind’s sidekick, however, will settle for two eggs over easy.”

xx

xx

xx

✺ ✺ ✺

xx

xx

Books by Annie Dillard:

xx

1974 Tickets for a Prayer Wheel

1974 Pilgrim at Tinker Creek

1977 Holy The Firm

1982 Living By Fiction

1982 Teaching a Stone To Talk

1984 Encounters with Chinese Writers

1987 An American Childhood

1989 The Writing Life

1992 The Living

1995 Mornings Like This: Found Poems

1999 For the Time Being

2007 The Maytrees

2016 The Abundance: Narrative Essays Old & New

Listen to Annie Dillard at a public reading in Oregon, 1989

xx

xx