SHOT IN THE HEART

Under the logo of their London production company “The Archers”, Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger created visionary and eccentric feature films, in which spectacular entertainment, smart narratives, and formal experimentation mix in a unique way. At the heart of their collaboration: the warm pulse of a deeply European humanism.

(Simon Schreyer, 2024)

One snow-glistening Winter night in the Alps, while hunting for voice samples on YouTube to strew over the soundscape of a chill out-mix for the radio station FM4, I stumbled upon a 1940s film titled I Know Where I’m Going!.

I put my musical task on hold and watched it the whole way through. Its plot follows Joan Webster, a young go-getter woman who is intent on marrying an industrialist on a remote Scottish island. But she is sidelined by destiny and falls in love with the impoverished Laird Torquil MacNeil who actually owns that island. On a walk around town, Joan asks: “People around here, they are poor, I suppose?” “Not poor, they just haven’t got any money,” Torquil answers, to which she replies: “That’s the same thing.” Torquil, astonished by her ignorance: “Oh no, it’s something quite different.”

It’s a dialogue that is as subversive today, as it was back then. As for the love story: I’m not easily schmaltzed over by romance films, but I Know Where I’m Going! brought a tear to my eye. Enchanted and shot in the heart, I watched all other films by its makers Powell and Pressburger in rapid succession.

I found out that Cecil B. DeMille, Josef von Sternberg, Stanley Kubrick, Nicholas Roeg, Ken Russell, and Derek Jarman had been Archers-advocates. Kate Bush was inspired to record an entire album dedicated to The Red Shoes in 1993, and David Bowie’s song lyrics to Let’s Dance (1982) seem like a page taken out of the diary of Boris Lermontov from the same film. Among their younger movie-directing admirers are Wes Anderson, Greta Gerwig, Yorgos Lanthimos, Joanna Hogg, Joe Wright, and Bong Joon-ho.

I wished I had discovered these trailblazers earlier, with their unconventional ideas, quick-witted dialogues, and the humanist messages unobtrusively hidden in them.

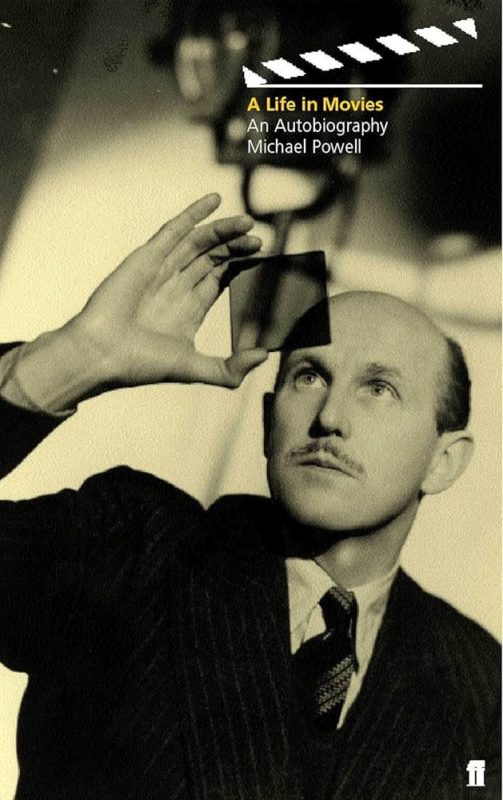

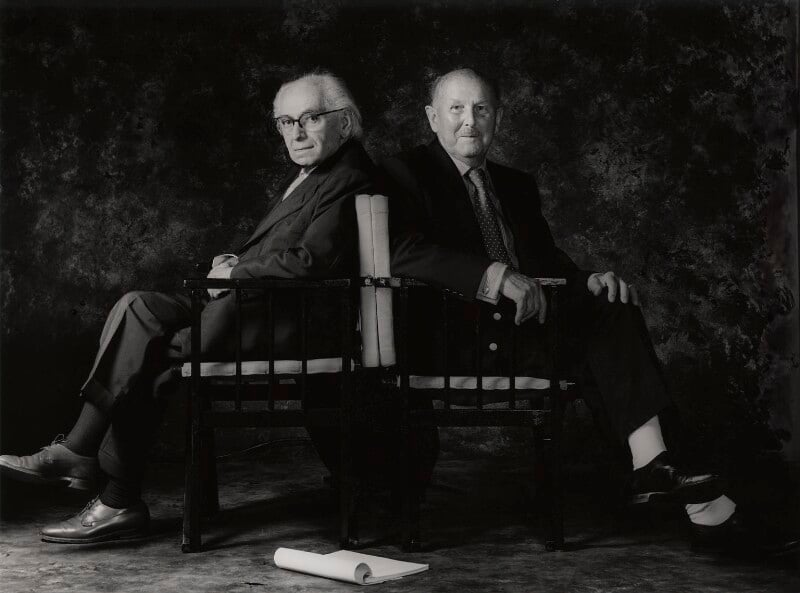

At the core of the Archers’ productions were two men: Michael Powell (1905—1990), very dynamic, very Celtic and tall, a bit of a womaniser I think, and a walker of the land; and Emeric Pressburger (1902—1988), bringing a Central European musicality and a deep love of classic literature to their partnership.

Pressburger, an Austro-Hungarian Jew, had found refuge in London after fleeing the Nazis throughout continental Europe where he had learned the craft of screenwriting in Budapest, Prague, and at Berlin’s UFA studios. It was only after the end of the war that he found out that his mother Katarina and many relatives had disappeared into the furnaces of Auschwitz.

It is this émigré experience that echoes in his screenplays: people arriving in foreign places by a twist of fate, coming to their senses and consciously noticing the nature and the details of these new places – more so than the folks who live there and are sleepily accustomed to everything.

Starting their collaboration in 1939 with rather unorthodox propaganda films for the Royal Air Force (Churchill hated them for their wry humour and irreverence), they soon shifted from post-Expressionist black-and-white gems to glorious Technicolor wonders in the mid-40s. All of their productions employed international crews and were daring enterprises – “tollkühn”, to hang a German term on it.

Film critic David Thomson, in the 6th edition of his New Biographical Dictionary of Film: “The great Powell and Pressburger films do not go stale; they never relinquish their wicked fun or that jaunty air of being poised on the brink.”

Cinema with a Capital C

The Archers’ world is populated with very English (and very heartbroken) colonels, love-crazed nuns, tortured prima ballerinas, alcoholic mine defusers, and foxy children of nature. Many of their films are about Amor’s arrow hitting its mark, turning the characters’ lives topsy-turvy, every frame inspired by artistic audacity and frivolous idiosyncrasy.

In many ways they are ahead of their times: The heavenly jury in A Matter of Life and Death preceded the founding of the United Nations by a year; and the jump cut in A Canterbury Tale, in which the medieval falcon turns into a Spitfire warplane, anticipated the transformation of a spinning bone into a spaceship in 2001: A Space Odyssey by almost 25 years.

How light-footed and smooth the audience is pulled through the plot by a mastery of narrative tone and editing rhythm, even in their longest (The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp), and in their most painful film (The Small Back Room). P+P films have the determined stride of an experienced highland walker.

As a hiker and traveler, I adore the dreamy and dramatic landscapes filmed by their cinematographers Jack Cardiff and Erwin Hillier – luminous, mystical, and reflective of their protagonists’ inner turmoil. Like in works by other directors excellent at filming scenery (Antonioni, Visconti, Tarkovsky, Polanski, Lean, and Kurosawa come to mind), landscapes in the P+P cosmos are silent, observant characters in their own right.

The Archers delivered films for a post-war audience that wasn’t just deprived of food but starved for colour, unity, humanity, and hope. They could only realise their unorthodox visions through financial backing from Arthur Rank’s organisation up until 1948’s The Red Shoes (which the highly religious Methodist Rank resented). After that, they were on their own and had to play the Hollywood studio game of the 1950s, in which British films had a hard time, as concurrent American blockbusters dominated the market.

Did they make concessions to the changing taste in the 1950s? Well, not many. They stuck to their standards as long as they could without appearing as an embarrassment to themselves. They could have let go a bit earlier, though: With the gaudy and lacklustre Elusive Pimpernel, the ultimately vapid whipped cream of Tales of Hoffmann, and the bizarrely cheap-looking Oh… Rosalinda!!, they crossed the cringe line a few times too often, for my taste.

In 1957, Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger stuck all remaining arrows back in the quiver and amicably ended their professional relationship.

In the 1970s, their work fell out of favour with a new generation of British filmmakers who turned their audiences’ eyes to social realism and a kind of TV formalism that broke away from opulence, fantasy, and high-voltage libido.

Even worse, the Archers were seen as un-British. Gavin Millar regarded P+P’s work as an “unashamed expression of artistic passion – from which the English recoil in horror.” The auteur-duo just wasn’t about “Keep calm and carry on!”, and “Get over it!”. They were weavers of lucid dreams, essentially, waking up to a more prosaic and sober way of storytelling. Ironic somehow, if you think of A Canterbury Tale, which is an almost meditative example of “Carry On!”.

By the early 1960s, Michael Powell was shunned by critics and the entire British film industry after the catastrophic première of his gutsy but hard-to-stomach Peeping Tom (realised without Pressburger, and starring Karlheinz Böhm as a femicidal snuff-movie maker). Having lived in a modest cottage well below the poverty line for almost a decade, Powell found ardent fans in Martin Scorsese and Francis Ford Coppola (who employed him as a senior director in residence at Zoetrope Studios), and: late love with Scorsese’s main editor Thelma Schoonmaker, whom he married in 1984.

In a posthumous love letter to P+P, iconic Scottish actress Tilda Swinton wrote about Powell: “In harmony with the Magyar romanticism and highly evolved humanism of Emeric Pressburger, we have, then, England at her very best: inclusive, passionate, radical, highly cultured, irreverent, open-hearted, fun.”

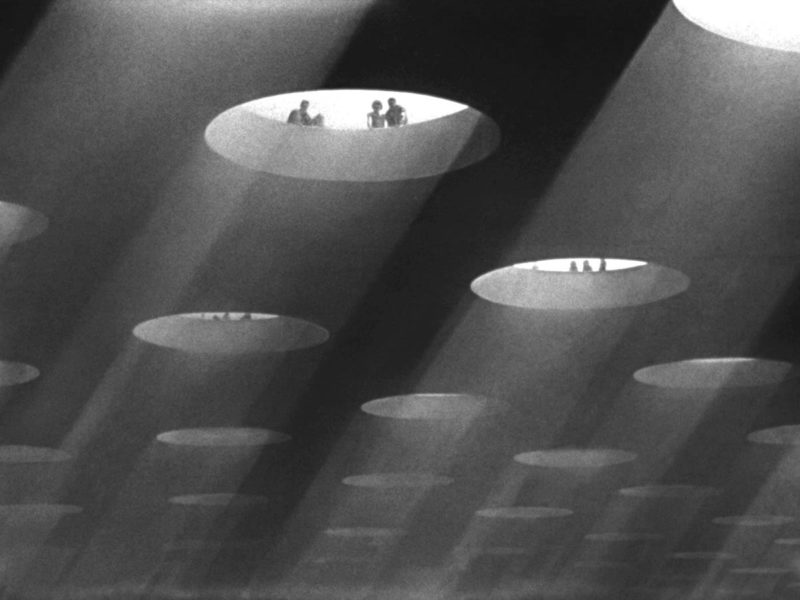

Foto: Ronald Grant/imago

x

After the Archers disbanded, Pressburger retired to writing first-class novels (Killing a Mouse on Sunday, The Glass Pearls), becoming more English than the English, and playing the violin while his beloved goulash simmered away on the stove. Asked why he put screwtops filled with water on the window sills, he answered in his thick Hungarian accent: “So that the spiders have something to drink.”

Unsurprisingly, he was friends with the anti-authoritarian German writer Erich Kästner and stayed at my hometown Kitzbühel’s Grand Hotel on skiing vacations, and even settled in the fairytale landscape of nearby Thiersee, in the mid-1960s. He moved back to England again after a few years, however, describing my fellow Tyroleans (undeniably aptly) as “violence-prone, arch-Catholic bigots”.

In old age, with the onset of senility, he was plagued by the creeping fear that the Nazis were still persecuting him.

Enkindled Eyes, Entangled Hearts

The Archers gave us new ways of seeing and experiencing Cinema with a capital C. They also gave us unforgettably happy endings, as well as unforgettably terrible endings. They performed cinematic experiments (trompe-l’oeil backdrops; filming to pre-recorded soundtracks a.k.a. “composed film”; switching between black-and-white and saturated colours) and showcased a panorama of passions taking centre-stage in the complicated mind of modern man and woman. And, above all: great acting.

We remember fantastic female performances: the debonair Deborah Kerr in Blimp and Black Narcissus. Moira Shearer – a miracle of effortless elegance in The Red Shoes and Tales of Hoffmann. Gone to Earth’s Jennifer Jones in arguably her best role. The sharp-witted, sharp-faced, and sharp-shooting Pamela Brown almost stealing the show from leading lady Wendy Hiller in I Know Where I’m Going!. And, of course, Black Narcissus’ devil in the doorway – Kathleen Byron, possibly the most beautiful woman on the silver screen in the 1940s.

We also remember the icy eyes of Conrad Veidt, Roger Livesey’s gentlemanly confidence, the suave fragility of David Niven, and Vienna’s finest, Anton Walbrook (né Adolf Wohlbrück), a forgotten Genius of Cool: all of them recurring ensemble members in the Archers’ canon.

Naturally, not everything is hunky-dory in my reception of their work: P+P were, after all, men of their Epoque. I read about the occasional streak of cruelty in Michael Powell’s handling of actors, and his credo that “true artists should be ready to die for their art” may be slightly at odds with today’s standards of mental health.

Then we have remarkably numerous women falling off the edge of some horrific precipice if you think about it: The Spy in Black, Black Narcissus, The Red Shoes, Gone to Earth, and Powell’s Age of Consent. There seems to be plenty a brink to be poised on, and many an edge to fall from. One of Powell’s most personal early films, The Edge of the World (1937) is all about the edge and how to fall from it. I assume, it is mostly a Powell-topos, and it evokes eery allusions to dark Druidic cults of sacrificing virgins, somewhere along Stravinsky’s Sacre du Printemps.

And as someone who has always had a soft spot for people with Down’s syndrome or any other mental handicap, the scene in which the young pilgrims make fun of the “village idiot” in A Canterbury Tale simply makes me sad (otherwise it’s a wonderfully eccentric, gorgeously shot film about the wartime Kent countryside).

What makes me happy watching and rewatching the films of the Archers’ golden run between 1943 and 1950 is best put in three words: atmosphere, atmosphere, atmosphere! What I admire about them as people is that Powell and Pressburger cultivated a deep, life-long friendship based on immediate trust, gilded by success, and eternalised by a shared imagination. What do I take away from them? The basic importance of “breathing the air, smelling the earth, and watching the clouds”. Not in a patriotic, but in a planetary sense. And something more: to take pride and to have faith in the human species, despite everything. That, I feel, is what we can learn from the Archers – now, more than ever.

❦

Bonus:

Martin Scorsese presents: Made in England

Trailer for the extensive BFI retrospective in 2023