Coast Highway

In early 2013, I drove down from San Francisco to L.A. in good company and took some notes on this mythical coastline between wilderness and eternity.

Big Sur! O Big Sur! What can one write other than an ode to this special place in time and space?

The rolling, round hilltops of the Santa Lucia Mountains floating on pillows of mist. Zen-like, gnarled branches of the conifer and the sugar pine, and tall, yellow beach grass trembling in the breeze. The fog wreathing ghostly fingers over the greens and browns of this land like wistful notes from a pedal steel guitar.

Land, that drops down dramatically into the vastness of the Pacific Ocean. Hardly ever a cargo ship or sailboat cuts through the churning, ice-cold waters below. You could draw a straight line to Japan, with nothing in between but blue expanse. “Big Sur, one of the most stunning meetings of land and sea”, wrote the New York Times. “Still the finest place on the planet to sit naked in the sun and read the New York Times”, wrote Gonzo journalist and literary icon Hunter S. Thompson, who worked as a caretaker in a hot spring resort (the future location of the Esalen Institute) in 1961.

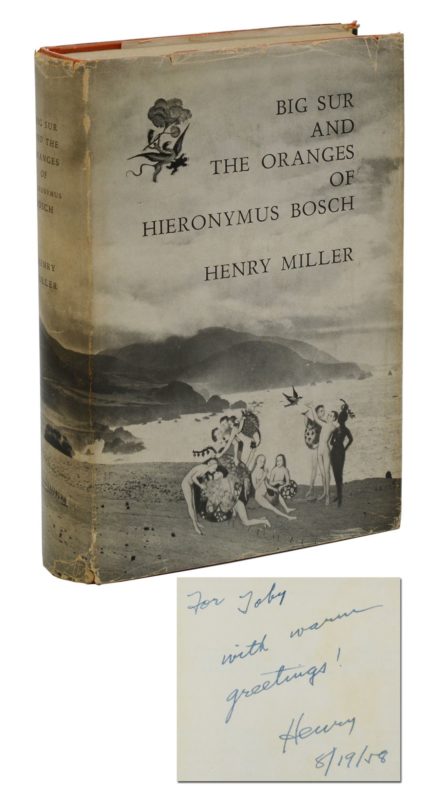

Big Sur is an Emily-Brontë-, or a Daphne-du-Maurier kind of landscape with wuthering heights and stormy shores, although neither of the two wrote about it. Henry Miller, who lived here (mostly in a bungalow on Partington Ridge) between 1944 and 1963 to escape the air-conditioned nightmare of modern America, did write about it: “Now and then a visitor will remark that there is a resemblance between this coast and certain sections of the Mediterranean littoral; others liken it to the coast of Scotland. But comparisons are vain. Big Sur has a climate of its own and a character all its own. It is a region where extremes meet, a region where one is always conscious of weather, of space, of grandeur, and of eloquent silence.”

Coming from San Francisco, we cross Bixby Creek Bridge in our night horse, a 2007 Mustang GT convertible.

All day long we have been chatting and planning, but now silence and a feeling of awe is growing between us. Furious clouds are chasing a soft-toned March sun, already past its climax. Into the taupe leather seats we sink and I put on CSN’s Carry On/Questions as we are heading towards the Point Sur lighthouse on its landmarking peninsula. But before we can reach it, it vanishes in a bank of clouds like a phantom ship.

We snack on apples, nuts, and grapes from a farmer’s market and stop for a walk in the flats, but the wind is whipping our hair and our words around in a decidedly rough manner, so we drive on, taking in the fragrance of herbs, wildflowers, and wet, salty sand.

Although there is a small, strewn-about hamlet called Big Sur, with not many more buildings than a post office, a general store, and a bakery, the name actually refers to the entire 70 miles of coast between Carmel in the North, and San Simeon in the South, reaching inland for almost 20 miles.

It is an archaic, exposed place at the edge of the Western World that has attracted few human inhabitants, even in the times of the First Nations. The nomadic Esselen were the only tribe to tough out a scarce lifestyle, subsiding on fishing and hunting small game. The fearsome presence of the enormous Californian grizzly bears who roamed the mountains until 1924, when they were extinct, must have been a considerable turn-off as well.

The earliest white settlers drifting in on the buffalo trails in the 1870s surely were hard-as-nails too, no-bullshit types of men and women, as portrayed by Gene Hackman and Liv Ullmann in Zandy’s Bride (1974).

Comparatively pampered in our cozy capsule and entranced by Joni Mitchell’s Songs to Aging Children Come, we meander through the foggy dusk toward Deetjen’s Big Sur Inn.

There we will have excellent fish stew and wine in front of a roaring fireplace with lazy cat Fabio purring at our feet, and then spend the night in one of the many Norwegian-style cottages and cabins. Ours is the New Room, built in 1951, with a gossamery Queen bed, lots of lace and shiny wooden surfaces, and a wood-burning stove, which I keep going late into the stormy night.

When I get up to put one last log on the fire, I watch the rain pelt the forest through antique wavy windows. As I learn the next day, Helmuth Deetjen, the Inn’s Scandinavian founder had bought a whole load of these window panes in King City, in the early 1940s, for five dollars apiece, and transported them over the mountains by mule, surprisingly arriving intact.

The Big Sur Inn, snuggled into the steep and deep Castro Canyon, opened as one of the first guest houses after the completion of Highway 1 in 1937. (It was reopened in 2021, after having suffered damage during the 2016 Soberanes fire, and being cut off by landslides and winter storms; ed.).

It is mildly famous because of its proud and simple elegance, its cuisine, and a low-key flair that has been appreciated by guests like John Denver, Robert Redford, Clint Eastwood, Kim Novak, Joan and Judy Collins, Joan Baez, Peter Sellers, Sharon Tate, Mia Farrow, and Jeff Bridges.

The next morning, just as we’re having a second coffee after breakfast (served until 12:00 PM, in true bohemian fashion. I recommend the tasty, crusty bread, and the Eggs Benedict), the door opens, and Trent Reznor and his wife Mariqueen Maandig stride like tranquil tigers through the sunbeams that cut the restaurant into dark and bright sections.

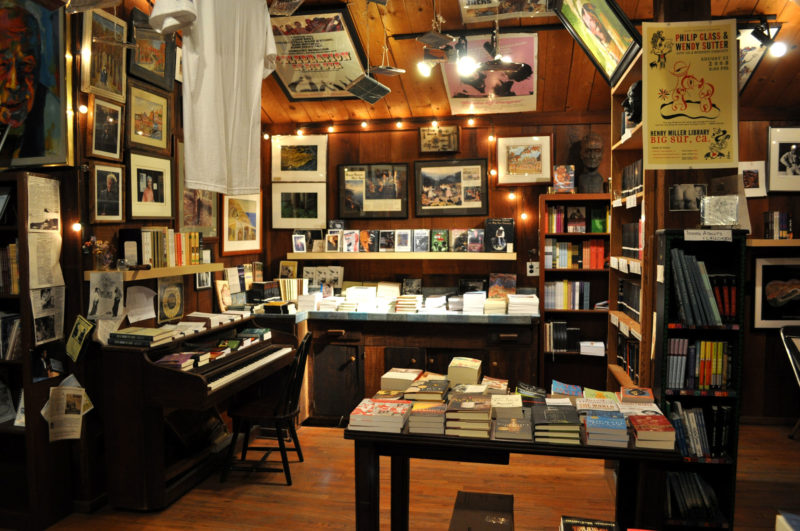

After a visit to the twisted, grey branches and purple sands of Pfeiffer Beach, and to the self-admittedly quiet Henry Miller Library, we continue our ride under azure skies and in blazing sunlight. Down comes the convertible top and on comes The Beatles’ Sun King on the stereo, and after that La Mer by Django Reinhardt. I look over at her, but she has fallen asleep with a small smile on the corners of her mouth. The tip of her palest-shade-of-apple-green scarf is dancing in the wind.

As often as the winding, narrow Cabrillo Highway allows it, I take glances at the hilltops above, soft and beige like a cougar’s fur, and at the glistening sea below. Later in the day, under huge, pink stratocumuli, we will take an espresso break before reaching the flatter, more bucolic San Luis Obispo county – lovely like Dorset, with heart-shaped rose bushes and communities actually named Harmony, Halcyon, Oceano, or Fair Oaks.

But for now, we are still on the warm, smooth blacktop of this magical stretch of highway snaking along the Big Sur coast. The night horse accelerates with a satisfied snort, and the enormous disk of the sun illuminates the Southern Hemisphere in front of us.

(Simon Schreyer, 2013; updated 2022)

✺ ✺ ✺