::: Notes on Sade Adu :::

I don’t like noon. Never have. The sun overhead, the cruelty of light, the busyness of business, the dragging middle-age of day. I am an evening person, a midnight rider, a son of the morning. Needless to say, these times of the day are personal, self-contained. The hours of the introvert. Yes, I am an introvert. Easily overwhelmed by noise and the brightness of high noon. My ebb is lowest in the early afternoon. My mood begins to rise as the day goes down. My mistress’ eyes are nothing like the sun.

However, the first time I heard her, it was noon. Tellingly, the sun was gone. Thick warm mists sprawled over the hills around Lake Chiemsee. A landscape covered in cotton. It was the spring of 1986, and I was eleven. My parents were squabbling, my younger brother a nuisance. I could not bear the thought of joining them at taking lunch in a loud Bavarian Gasthaus, so I stayed in the car out on the parking lot next to the lake by myself. I lay back on the backbench, resting my knees against the back of the front seat.

As thick veils of rain washed over the land, a succession of rimshots, interspersed by pairs of snare drum beats, came on the car radio. Out of the intricate rhythm grew an edgy and flexible guitar line, and then her voice set in. It was singing to me, soothing my little troubled-boy soul. I didn’t know what romance was, or a ‘taboo’, or, for that matter, what a rimshot was. But I knew that voice. It came from the place where the priest said God resided, even if I had my doubts about God then as I do now. I didn’t even think of God, nor of a Goddess, mind you. I just wrapped myself up in the frequencies of that voice like in a cashmere blanket.

After the song had ended, I turned the radio off and continued to listen to its harmonies inside my head and the rain outside the car. When my family returned from lunch, they were in a good mood, and so was I! Although for a completely different reason. I hadn’t fed my belly, but I had fed my soul.

So much time and effort in our culture is spent on defining what it means to be ‘cool’. As a consequence, the term is inflated, and being inflated surely is anything but ‘cool’. Someone said coolness describes a hot heart guarded by a detached mind. Others say it means not being needy of external validation. Someone else wrote that the God of Cool went by the name of Òsun and was revered in the Yoruba tradition among the Gola people of Liberia and Nigeria, in West Africa. An almost stoic concept of beautiful dignity held high by the Yoruba culture is called itutu, which means acting unagitated, or calm, even in the face of turmoil, tempests, and tax returns.

Also from Nigeria came a university lecturer by the name of Adebisi Adu. In the mid-1950s, he fell in love with a white English nurse, Anne Hayes, and they had two caramel-coloured babies: Banji and Helen Folasade, Folasade meaning ‘wealth is a crowning glory’, shortened later to Sade, pronounced Sha-Day.

By the time Helen was four, her parents had split up, and Anne left Nigeria with her two small children and moved back to her socialist family in Essex. “I don’t know if it’s true about mixed marriages,” she said in a TV interview. “I’m sure it isn’t in every case, but basically, my mother and father didn’t get on very well. They were only actually together for four years — my first four years, anyway.”

I hardly know anybody who wasn’t in some way traumatised by their parents’ opposite sides clashing – different tempers and strata of society, cultural backdrops, and colours of skin. And, in that sense, every marriage is a mixed marriage, that, at some point, starts losing the magnetism of attraction and becomes just opposites. It is painful to experience that the unified forces of love that created you are falling apart, that these opposites live on in you, opening up a chasm of contradictions within yourself, making the validity of the mix (that is, you) questionable.

There are only a few ways to deal with this. One of them is trying to understand both parents psychologically, and continuing to love them both for who they are. It is the straight way to maturity and learning about the seriousness of life. Another way of dealing is channeling your own emotions. That’s the way to either sports, drugs, dance, adventure, and/or creativity.

Sade Adu, I’m pretty sure, must have been an observing, understanding child, protected by her elder brother in dull English suburbia full of old white folks, in the 1960s. About her mother’s home country, she said: “It can be very hostile, England. Not just to me, to everybody. England’s like a sour old auntie. You go and stay with her although she criticises you all the time and doesn’t treat you right, even when you’re doing your best. But you keep on loving her, in a certain way. And then you die. Those bitches always outlive you. ”

I’m sure teenage-Helen had an instinctive inclination towards justice, and that she inspired awe in her peers by her beauty, her elegance, and her dignity. Dignity in the sense of having poise, acting calm and collected, not relying on what others think of you, being a self-sufficient, self-contained unit. To be so, one has to seize the moment and cherish the day. Sade: “Whatever I’m doing, I’m in that moment and I’m doing it. The rest of the world’s lost. If I’m cooking some food or making soup, I want it to be lovely. If not, what’s the point of doing it?”

©P.Natkin, MGID / MTV

So, seeking fulfillment and perfection isn’t limited to the act of writing music, as she told Wax Poetics: “I love making music more than anything else that’s doable. It just has to be the right moment. If there’s stuff in my personal life that needs fixing, I’d like to fix it before I record. I don’t know if that’s procrastination or not. I’ll go: ‘It’s time to start writing music.’ Then there’ll be a cobweb up in the corner, and I can’t possibly start until the cobweb’s gone.”

Which is the mark of the performing artist: the dedication to every detail of clothing (she initially studied fashion design at St Martin’s School of Art), every instrument in a track, each syllable in a lyric, every cobweb up in the corner. It might just as well be procrastination. But what binds the listener to the experience of hearing her songs is exactly this concentration on the detail, just like the greats she admired since her teenage days, when she squatted in abandoned Tottenham high-rise buildings, listening to pirate radio stations: Billy Holiday, Frank Sinatra, Nina Simone, Donny Hathaway, Chet Baker, Marvin Gaye.

What binds me to Sade Adu’s personality, besides her practical wisdom and her beauty, is her self-deprecation and her understatement: She likes to liken her forehead to an oversized grapefruit. She admits that she often runs late (not just concerning the releases of her albums), and that she often misplaces her lyrics book. When her first band Arriva turned her down as a backing (!) singer, they returned to her two weeks later, because they couldn’t find anyone else. So she was in for the gig.

When her second band, Pride, broke up, she took along guitarist and saxophonist Stuart Matthewman (her musical right-hand man and co-writer throughout 40 years of collaboration), bassist Paul S. Denman, keyboardist Andrew Hale, and drummer Paul Cook and formed her band, Sade, in 1984. (The band also released tracks sans Adu under the name Sweetback.)

Producer Robin Millar booked Sade in for a week of studio time: “We used a real piano and a Fender Rhodes piano, painstakingly synching them up,” Millar recalled in The Guardian. “Of course, three years later, you could do this easily, using MIDI. But it probably wouldn’t have sounded the same.” Then Millar sent out the demos, but every label turned them down: “They thought that the tracks were too long and too jazzy. They said: ‘Don’t you know what’s happening? Everything is electronic drums now: Tears for Fears, Depeche Mode.”

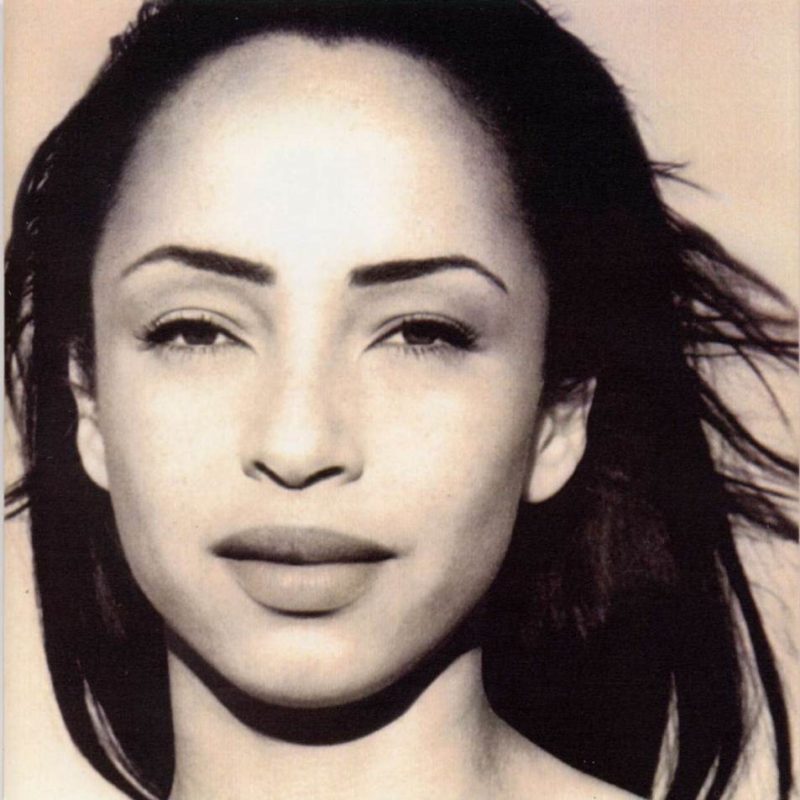

But Sade Adu had a vision she was convinced of, and: She had a face. The face. In 1984, the British style magazine of the same name put a Nick Knight portrait of her on the cover as the discovery of the year. A few months later, Sade released their debut album Diamond Life, at 10 million copies, one of the best-selling debuts of any British female singer in history. The album versions of Your Love Is King and Smooth Operator were exactly the way they were recorded – the same versions that were rejected by everybody. She was in on 14 % of the record sales. How does one get such leverage? Sade: “The more you defend yourself, the more frustrated you get. So you try to divorce yourself from the situation and you remember who you are, and you carry on.” Good advice. I’ll remember it next time when I talk to my banker.

Altogether, Sade sold more than 75 million copies worldwide. To this day, she is the boss. She will write a song when it comes to her, like Is It A Crime which originated during a soundcheck. She will record a new album when she feels ready, not when the record company calls. She has the last word on which instrumental take to be used on a recording, even if the guy who played it wants to do another take, and justifiably so: Hardly a cover version, or remix has come close to the original recordings of her songs, except for the odd dub-reggae remix from a master’s hand, or a brilliantly sampled guitar-line in a now classic hip-hop track.

Timeless and instantly identifiable, Sade’s music is the ultimate bar music: sad but seductively sensual. Her most famous song is about a slick yuppie with eyes like angels but a cold heart. In short, a greedy bastard like they were worshipped in the garish 80s, a guy for whom nothing would be sufficient, least of all himself. For me, the smooth operator was never the male subject of the song, but, of course, its singer. No need to ask.

“We move in space with minimum waste and maximum joy.”

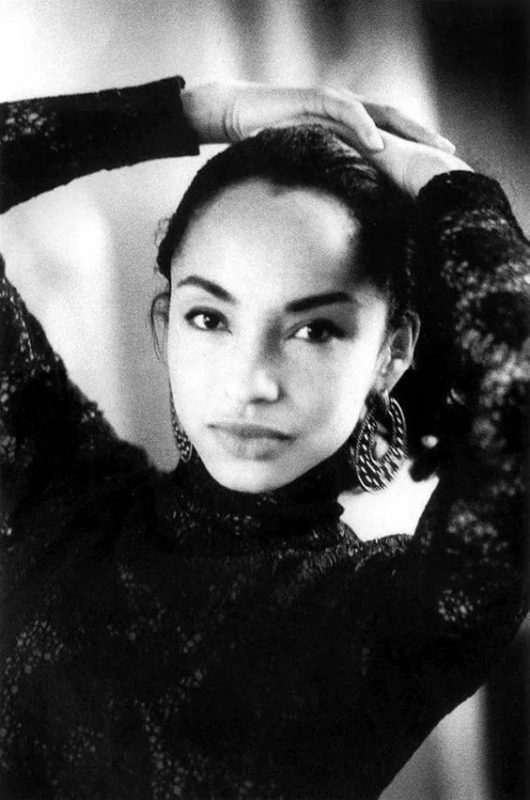

In her singing and stage presence, Sade Adu is all about reduction and minimalism. She lets you feel her world-weariness underneath that granular contralto, creamy as nougat sorbet but with a delivery weighted by a core of lead. There is no agony or over-acting, not even a display of extreme range or vocal artistry, simply because she knows (just like another iconic singer with an untrained voice, Astrud Gilberto) that this is not her forte. Aretha, Tina, or the flamboyantly extravagant Erykah, she is not. One could say Sade is too English for that. Also, her live performance is cut down to the essential – a shaking of the hip or a flick of the ponytail.

© Vogue Italia

Where does that reduction of movement come from? Once, in an early live show, her stiletto got stuck in the make-shift stage built from beer crates. Through this restriction of movement, she said she had learned about transferring physical energy into vocal energy. She also doesn’t think of herself as a great dancer anyway: “I feel like even if I just shuffle my feet I’ll look ridiculous,” she once explained defensively in an interview with RBMA. And, on a different occasion: “I feel at home in the studio, but when playing live, all I do is just try to avert a disaster, really.”

Disasters and hard times did strike in her private life: the death of drummer Dave Early, her producer Robin Millar going blind while recording her second album, and an altercation with the Jamaican police who tried to have her bribing them after stopping her for reckless driving in the 1990s. Sade failed to appear at her court hearing and hasn’t returned to the Caribbean island ever since. But she had a baby there, in 1996, a girl called Ila who, in 2016, transitioned to become Izaak.

Today, as always, Sade is a reserved person. She lives with a regular bloke, an ex-Royal-marine, in a self-renovated cottage with sheep and pigs in the Cotswolds (a range of rolling, woody hills in the English West Country). Sade: “I always said that if I could just find a guy who could chop wood and had a nice smile, it wouldn’t bother me if he was a thug or an aristocrat, as long as he was a good guy. And I’ve ended up with an educated thug.”

This Far, a vinyl collection of her six albums, was released last year (2020), and there are rumors about a studio album being in the works, but it’s a rumor. Sade couldn’t be further from entertaining a Twitter account or a personal Instagram. The tabloids have long ago given up on her. She almost never grants interviews. It is known that she has a fondness for interior decoration, classic reggae, a little bit of weed and red wine in the evenings, collecting books, and inviting close friends to dinner. She is not a recluse, but consistently private.

These days, I don’t listen to sultry 80s-smooth-jazz with sassy saxophone solos and slapped bass guitars, nor to any of Sade’s music, but each time one of her songs is played somewhere, I’m reminded of her dignity and her elegance. And of the first time, I heard her voice during a quiet rainstorm, back in the tunnel of time. Like another British pop heroine (albeit a fictional one), Modesty Blaise, Sade Adu is an inner go-to for me when I require a strong spine, or just a hint on how to deal with a certain life situation. And, serendipitously, I am being given hints.

Like a few years ago, on a black sand beach on a volcanic island north of Sicily, when an extended version of Hang On To Your Love wafted over from a nearby bar. It was noon, and the Mediterranean sun was relentless like a wrathful Old Testament God. I got up, looking for forgiveness, and coolness, and noticed that our host’s Germanic father had painted a sentence along the round inside wall of the blindingly white windmill that had served as his writing studio. I walked closer and stuck my head inside the doorless entry to inspect the slogan. It read: Genüge dir selbst – Be content with yourself. I stepped inside. The air in the room felt like cold milk on my skin. I sat down in the shade for a long while, looking out over the blue Aeolian horizon, listening to the music.

(Simon Schreyer, 2020)

Sources: The New Yorker, The Guardian, Red Bull Music Academy, Wax Poetics, NPR, The Fader

Sade ::: Studio Albums

Diamond Life (1984)

Promise (1985)

Stronger Than Pride (1988)

Love Deluxe (1992)

Lovers Rock (2000)

Soldier of Love (2010)