FOR THE RECORD

xx

The Police created and explored a sphere of music on the far side of Post Punk, New Wave, and Reggae. In their three individual, and individualistic, memoirs, Stewart, Sting, and Andy explore their past. Here are some reflections on what they have in common, and what sets them apart as storytellers, as well as contributors to their unique signature sound.

(Simon Schreyer, 2018)

xx

xx

When the Police bowed to a frenzied crowd and packed up their gear after their last concert at Madison Square Garden on August 7, 2008, everyone knew that the band was history.

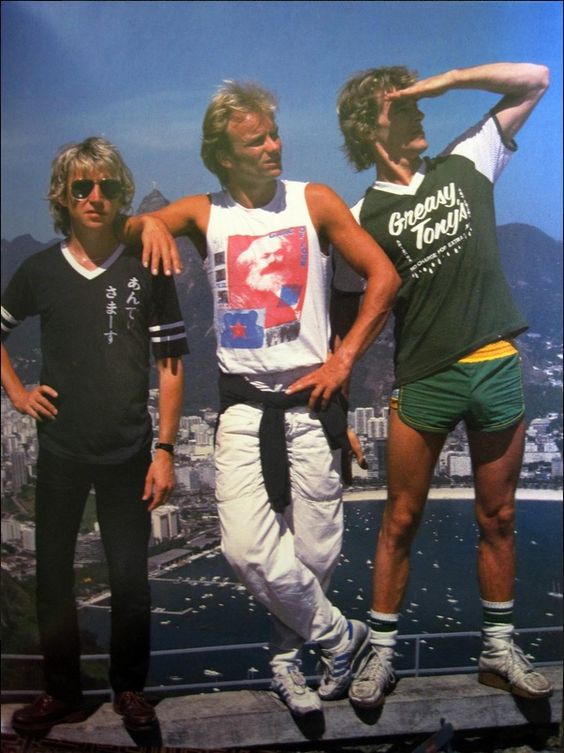

Before their reunion tour in 2007/8, they had already written history, but there had always been a slight chance that Sting (vocals, bass), Stewart Copeland (drums), and Andy Summers (guitar) could restart the band; a band that Sting called, in the documentary Better Than Therapy, a “sort of cock-eyed machine”.

xx

xx

The sonic emanations of that cock-eyed machine were the first music that I was completely mesmerized by as a child. I was born in 1974 and must have been six or seven when I heard the galactic reggae chops of Walking On The Moon reverberating from a transistor radio on an Adriatic beach. I was transfixed and changed forever. It was the first music I heard that gave me the impression that it had been directly made for me. It was clearly magic.

It was about six or seven years later that I found out who that song was by, and by the time I was a teenager, the Police had already split up for good. So, I discovered my first favorite band shortly after their disbanding. Lucky me. Also, I was the only human being I knew (remember there were no internet fan threads back in 1986) who liked them, which made me proud and purified me enough to maverick into listening to jazz on my very own, while everyone else my age fell for Jacko, Kylie, and A-ha.

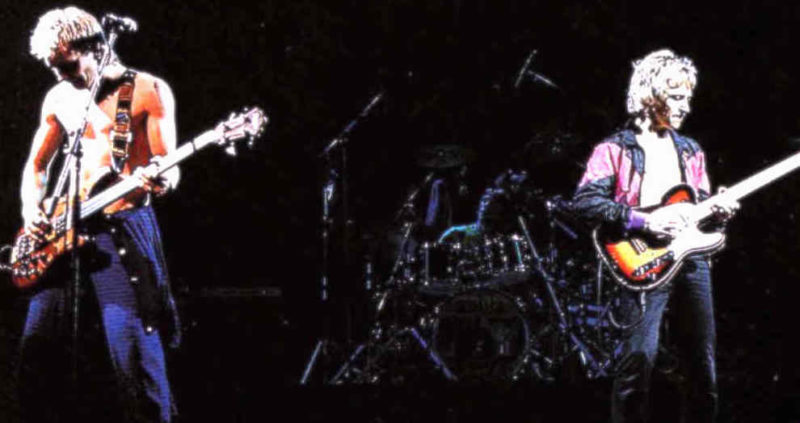

I can understand if someone hates the Police and thinks of them as a plastic pop band with an egomaniac singer, that hung on to the tattered tails of punk, or, more to the point, thinks that they made apt music for a six-year-old. But then, what are you doing here, reading all this splutter? And, besides, between 1977 and 1984, the Police delivered powerful concerts around the world and recorded five albums that are to this day as modern as they are timeless.

xx

xx

And, for the record: All three members wrote down their own history of the making and breaking of this most signifying and original pop band of their period: Andy Summers in his autobiography One Train Later, Stewart Copeland with Strange Things Happen – A Life with the Police, Polo and Pygmies, and Sting in his memoir Broken Music.

As diametrically diverse as the three ingredients of the Police’s sound are, as opposite and idiosyncratic do their respective books read. What they have in common is the tempus of their storytelling: Paralleling their immediate, forward-moving sound, all three books are written in the present tense.

What also comes across in all three books: Stewart, Sting, and Andy got their technical grounding in jazz music. They were also, long before they knew each other, fans of rock trios like Cream and the Jimi Hendrix Experience.

The Police were a three-piece band – a triangle – and only for their first three albums were they an equilateral triangle. Then, with the power shift towards the singer, it became of an ever more obtuse shape.

In a triangular construction, the push and pull of forces are more dynamic and dramatic in a more confined space than within a square or a pentagon. In that regard, the Police were always a kind of geometrical phenomenon, in which lines, limitations, directions, circles, and intricate patterns were as defined as the musical color range of their songs. Think of Kandinsky’s Arch and Point as a sound.

In every trio, there is always the odd one out in some regard: Andy is smaller and quieter than the other two tall alphas. He is also older by a decade. Stewart is the American among two Englishmen, the only one from a rich background, and he has got the sitting-down job while Sting and Andy work the stage out front.

Sting is the odd one out because he is the gifted writer to put the pop into the pop song, which the other two clearly aren’t (Sorry, Miss Gradenko, and sorry, Andy’s Camel!), and, most importantly, he is the frontman, actually holding down three jobs in the band, while the other two only have one thing to do. Which, we have to agree, they can pull off like nobody’s business.

What I did not expect was how compelling and enthralling all three would write down their respective story. And as these autobiographies are, most likely, the last creative output from the Police, we may as well cherish them, and give them a closer look.

xx

xx

xx

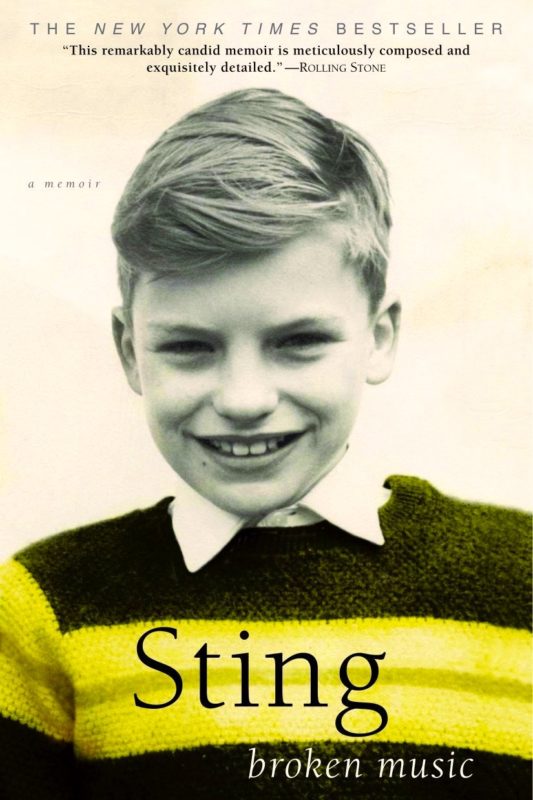

Sting: Broken Music (Simon & Schuster, 2003)

![]()

xx

A yarn well-spun. Sting is a good raconteur: eloquent, elegant, and erudite – as you might expect from someone who more than just dabbled in Jung, Buckminster-Fuller, Bowles, Nabokov, Elizabethan lute music, and Kurt Weill. Occasionally, I had the impression as though the information he chooses to share with the reader is put through a filter, between the actual happenings and how he wants you to read them, and thus perceive him.

But maybe that filter is just called good editing. It’s a bit like a psychiatric session with a patient who knows that his doctor has great taste in literature.

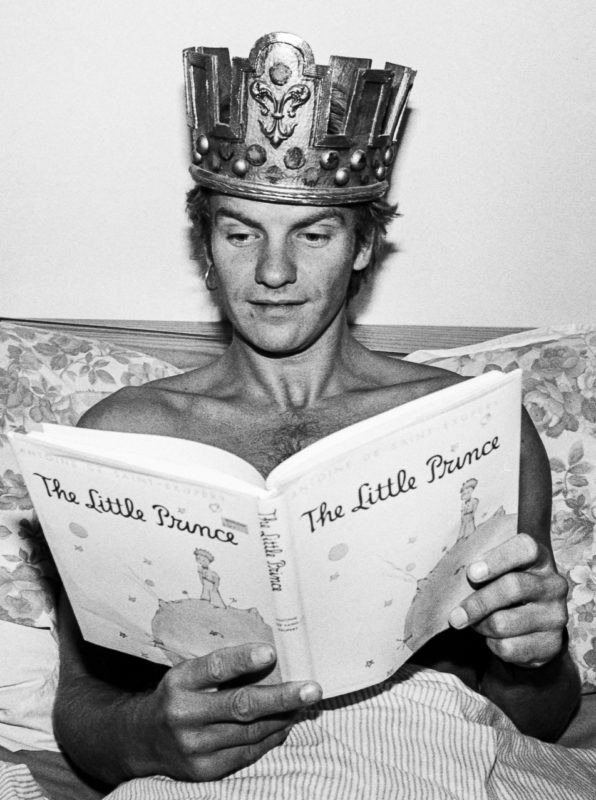

Sting’s narrative starts on a rainy night in Rio de Janeiro, in the late 1980s, and from there takes off rather adventurously when he and his wife Trudie are invited by a shaman of the jungle to partake in a psychedelic journey via a medicinal potion. It is known as Ayahuasca, a bitter-tasting, black concoction that induces puking (not so with Sting, however, which says something about his self-control) and a hallucinatory flight down memory lane, straight into the primal subconsciousness.

The connecting subplot of this psychedelic plant experience, however, gets lost throughout the book and only ever so slightly ties the knot of the overall plot at the end, as a coda of sorts. The central image is of a radiant blue flower with a golden pistil (the ultimate symbol of the romantic troubadour since the time of the German poet Novalis), into which Sting is sucked, like into a funnel of life.

Sting’s trip is the catalyst of a series of biographical jump-backs, and takes the reader into a starkly personal zone, even onto darkly Dickensian terrain. We hear about a childhood in the industrial harbor town of Wallsend on Tyne, today a part of Newcastle, the scene of a series of awkward incidents that revolve around his parents’ stormy relationship, resulting in a break-up of their marriage.

His mother is a gifted singer and piano player in her spare time, and her eldest son’s first memory is that of him sitting underneath the piano and watching her feet pump the pedals in tricky counterpoint movements to the notes played far overhead. It is also her who coins the memoir’s title when young Sting plonks away on the piano in inadvertent Schönberg-style.

He describes her as a „slim, attractive woman with long fair hair, startling green eyes and good legs…“, who was frequently wolf-whistled after in the streets. The public exposure of his mother’s sexual attractiveness seems to have been an early psychological challenge for Sting, and probably more so to his father, an Irish milkman with a good heart and manly handsome looks.

Another factor contributing to Sting’s well-publicized physique (apart from his parents’ winning DNA) is his first job of helping his Dad on the delivery rounds, carrying heavy crates of milk bottles and, apparently, drinking lots of it too.

The backdrop to these childhood scenes is a huge steel hull at the end of the street: the giant shadow of a cargo ship being built, the shadow of industrialization itself, as well as the promise of faraway seas, the lure of the Great Journey. It is also a man-made invention that feeds but also eats up the people living in its proximity. The dark hull is an archaic landmark in Sting’s soulscape, familiar from his solo album The Soul Cages (1991) and his musical The Last Ship (2013).

I also read (with mischief, I admit) about some of the mishaps that occurred in this man’s life often wrongly accused of glib perfection by jealous hacks and hackettes. There is the story of young hormone-overloaded Sting who drives the car with one of his first dates inside straight into Newcastle harbor and has to be rope-pulled out by his father, who starts flirting with Sting’s love interest much more successfully than him.

Then, there is the Spray Can Incident, when Sting had to wear huge shades on a live broadcast of the Old Grey Whistle Test, after accidentally blinding himself with hairspray. Or, the unexpected phone call from Miles Davis, who calls Sting unabashedly ‘a big head’, then tells him that he wants him on his record (You’re Under Arrest, 1985), not singing, not playing bass, but reciting the Miranda rights (the Police-Chief, hint-hint, you get it…) in French, of all languages.

Also, there are shrewdly strewn traces in the text of how one or the other song idea was received, such as his walk back from his young love Deborah’s house on a moonlit night, completely devoid of gravity.

Broken Music is foremost the account of a blond Newcastle urchin, who sees the Queen Mother roll by in a Rolls-Royce at a parade and swears that one day he will ride in such a golden carriage himself. It is this fulcrum moment of his childhood that provokes Sting to scheme his escape from the mythical fisherman’s soul cage. It is also a coming-of-age story, the account of a hard struggle between trying to survive as a school teacher and working relentlessly to get his career in music going, with no financial or social safety net. People nowadays forget that Sting put a lot on the line to make it before he ran into Stewart Copeland in the mid-70s.

There is of course blood on the tracks of the Police’s success, and in Sting’s case, it’s the painful split from his first wife, Northern Irish thespian Frances Tomelty, who had born him his first son and had taken him under the wing as a kind of publicist, and frankly, as an experienced, wise woman.

The memoir tellingly ends just before the Police hit it big time. Ever since then, Sting’s life has been ferociously documented by the media, liner notes, interviews, unauthorized biographies, his ex-band members’ photographic and cinematic output, etcetera. However, this is different from the books by the other two Police members, who expand at great length on the golden days of the band.

In Broken Music, Sting bares a lot of his private mythology with its shepherds, priests, flocks of crows, broken walls, fallen angels, castles with lonely kings inside, or the twisted sons of a fog bell’s toll. And we learn of his numero uno passion in life: Music. Sting is a journeyman, a perennial student of music, just like he is a student of yoga. He knows that there is always something more to learn, another instrument, another scale, another idea of harmony. It is a never-ending lesson.

xx

xx

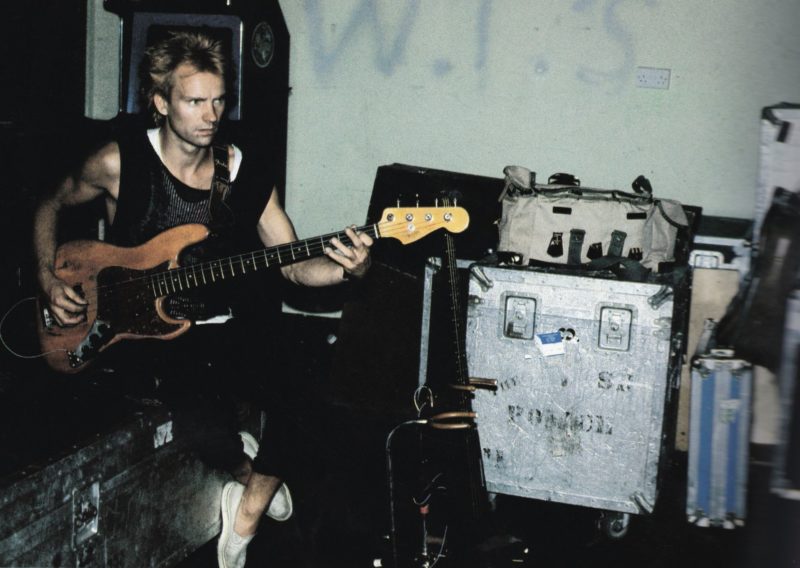

Many bands would call themselves lucky if they had a bass player like Sting. His sinewy basslines are minimal but maximally propelling the dynamics of his songs; the sound of his Fender Precision is visceral, growling, and barking at times. It is a distinct fourth voice within the sound of the Police, and it is still a miracle to me how he can hold down the counterpoints on his bass and sing so freely over them.

Not to talk about his other gifts: The extreme range of his wailing tenor that has become a cross-culturally identifiable sound. His songwriting craft is pretty unique considering the surprising quirky leaps that his arrangements take, and so is his dark and wicked lyricism about topics like isolation (Message in a Bottle), suicide (Can’t Stand Losing You), loneliness (So Lonely), pedophilia (Don’t Stand So Close To Me), and about a hooker (Roxanne) and a stalker (Every Breath You Take, strangely still one of the most played songs at weddings!).

Sting is great at condensing emotions, dreams, and stories, and his memoir is an exercise in expanding on the emotions, dreams, and stories that usually are the raw material for his songs. Not an easy exercise, and in that regard, Broken Music is a worthwhile reading experience.

Still, it is a little bit disturbing to learn how intensely introspective, fragile, and mentally wounded he is, never mind the Wiltshire mansion and the vineyards in Tuscany. This reminds me of a metaphorical scene out of Julian Schnabel’s Basquiat movie with Jeffrey Wright, in which the little prince bangs his golden crown against the window bars of the prison that is his life, thus creating a bell-like chime, entrancing everyone in earshot.

There certainly is a sting in Sting’s soul. But there you go, once again: Grit, oyster, pearl.

xx

xx

xx

Stewart Copeland: Strange Things Happen – A Life with the Police, Polo and Pygmies (Harper Studio, 2009)

![]()

xx

Strange Things Happen is an animal of a different breed compared to the other two Police memoirs. Which matches its author’s personality just fine: It’s loud, it’s funny, it’s irreverent, and it gallops along on high-powered energy. It also differs regarding its construction, which follows no chronology: Stewart jumps in and out of chronological order in a manic frenzy.

His book starts with a letter to a friend in Beirut, where he spent nine years of his childhood as one of many American diplobrats. The rhythms and songs of the Middle East are his first musical playground, learning the baladi rhythm and the dabke dance from a Lebanese drummer.

From there he springs forward into lesser-known areas of his life, like film score composition (Rumble Fish, Talk Radio, Wall Street, etcetera), opera (Stewart has composed three operas), ballet, video game soundtracks, jamming at his famous studio, the Sacred Grove in L.A. with guests like Snoop Dogg, Jeff Lynne or members of Primus and the Red Hot Chili Peppers, and touring with an Italian Taranta orchestra.

He also takes the reader backstage at the Police reunion tour, but not so much into the band’s heyday, which Andy covers more extensively in his autobiography One Train Later.

Stewart’s book frequently makes for great gonzo journalism. Many of these biographical snapshots were intended for drummers’ magazines, but apparently, he was convinced by Harper-Collins to collect and edit them for this book.

Most of the anecdotes groove along irresistibly, so much so that I can only recommend to the reader to purchase the audiobook! Stewart is a fantastic narrator of his own wild prose (and, judging harshly from some of the musical interludes, a joyfully abominable singer). It’s the same contagious energy that infuses his voice-over to his 2006 film Everyone Stares: The Police Inside Out, which made it to the Sundance Film Festival, where it became a bit of a nucleus for the band reunion in 2007.

A lot of this vigor seems to stem from his father, a CIA founder member and agent, who passed on an All-American chest-out, Gung-Ho mentality to his sons. It has to be noted that the founding of the band was Stewart’s idea (together with the Corsican guitarist Henry Padovani), and it was his brothers, Miles and Ian, who ran the logistics and management of the Police like a pirate enterprise from the beginning.

xx

xx

At times, this bold stance gets on my nerves, though, for example, when Stewart likens touring the world with a rock band to “…burning down your towns, raping and pillaging across the land!” I am not sure how amusing these allegories sound in the ears of his Lebanese childhood friend and pen pal Iskander. With the “Ol’ Glue Factory” and its dirty history in mind, there is little amusement in such an unempathetic attitude.

Also, there is little depth there. Stewart is mostly busy steaming along, without getting all too philosophical about anything. He himself probably wouldn’t deny this. Unlike the singer and songwriter with whom he shared his greatest success. As he said about the differences between him and Sting in an interview for the Police reunion: “I am loud and shallow. Sting is deep and mysterious. Whenever I move about normally, Sting is in the way of my elbow, and if I hold a large beer, some of it will spill on him.”

And about his role in the band: “For Sting, music is an escape to find serenity. For me, it’s a way of destroying serenity. My purpose is to burn the house down. So, when the two of us get together to make some music, we are trying to do two completely different things. And since it’s kind of important and we take it very seriously, we are going to clash.”

During his anthropological sound expedition to Africa, as The Rhythmatist (also the title of his first solo album), he is drumming in the savannah to a pack of hungry lions, who start attacking the flimsy wire mesh cage that protects him. Stewart literally plays for his life. One of the lions walks away in frustration and flashes him a look that reminds him of a certain singer from Newcastle.

What can be learned about Stewart from his book is that his life in drumming is a headlong joyride. His challenge: Learning to play exalted, yet collaborative. As a movie-score producer with highly developed conceptual faculties, he has pleased directors from Oliver Stone to Francis Ford Coppola by composing “happy/sad, or sad/happy music on demand”.

What many Police fans may not know is that Stewart Copeland is an accomplished horseman, a prize polo player even. In fact, it was a polo accident, in which he broke his collarbone, that prevented the band from getting back together for recordings in 1986 (thus the brutally overblown drum machine on that bizarrely useless re-recording of Don’t Stand So Close To Me).

Not an easy task at all, for a flash of energy with a Wookie-like stature in short shorts – his trademark stage gear around 1980. It’s the long, lanky limbs and a constant hyper-nervosity that informs him as a powerhouse drummer. His playing is melodic, snappy, and extremely busy. The latter, of course, much to Sting’s chagrin.

Boredom and sultriness are not up any Copeland’s alley. Stew is all about immediacy and drive. His drums are, in his own words, his “chariot of fire”. This blazing enthusiasm comes through a lot in his capabilities as a memoirist as well, for example, when he talks about trying to break into London’s post-punk vacuum as a self-styled anonymous guitar hero named Klark Kent, or his many mishaps, which he dishes out with self-deprecation.

Strange Things Happen contains a hilarious selection of those stage accidents and slip-ups. During a guest spot (with, I believe, The Foo Fighters), his flexy headband starts to move north up his skull slowly, so he rips it off between two beats, and with it, the in-ear monitoring set that is taped to it. Everything he can hear now, is his drums and the abruptly deflating roar of the crowd. Another time, he misses the encore as the only band member, even sabotaging it since he had already dashed backstage to perform his ritualistic post-show hot shower.

And then there is the tuba story: Stewart buys Sting an antique tuba in a Viennese music shop for his birthday (“The brass section’s bass instrument for the bass player in my band”, he notes). After the show that same evening, which is spiked with mistakes, Sting and he quarrel and Stewart bellows: “Give me back that f*c&ing tuba, you c5*T!” to which Sting calmly replies: “Can’t. Trashed it.”

Strange things certainly happened to Stewart, and fame seems to be no less a strange thing to ride out. On rock star life becoming stale quickly, Stewart writes something very perceptive: ”If you’re an eagle, you’re probably over having the whole world there at the end of your talons – it’s just another day in the boring old sky.”

xx

xx

xx

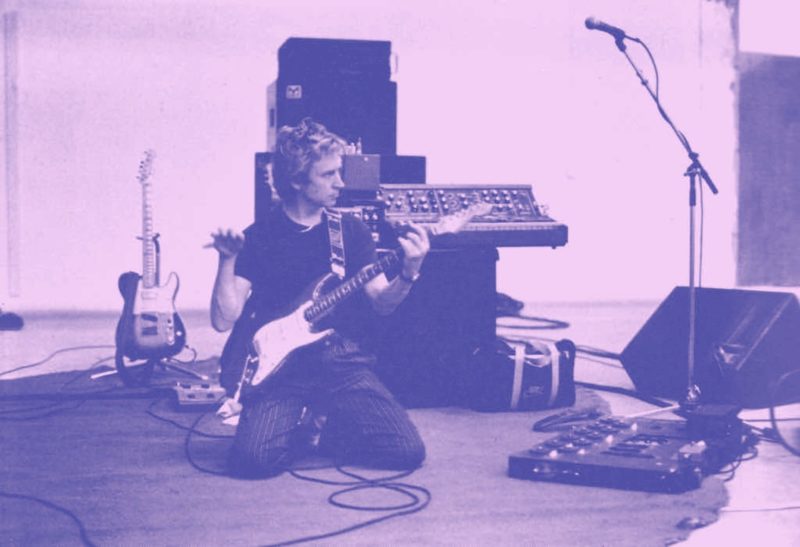

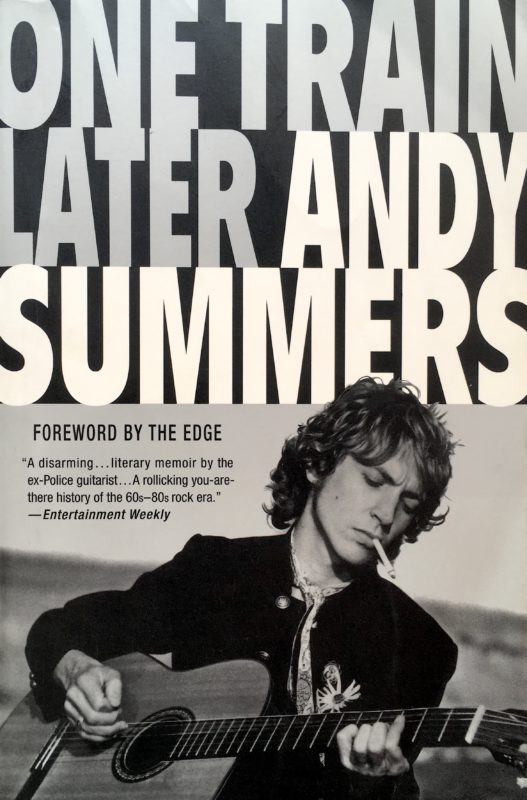

Andy Summers: One Train Later (St. Martin’s Griffin, 2006)

![]()

xx

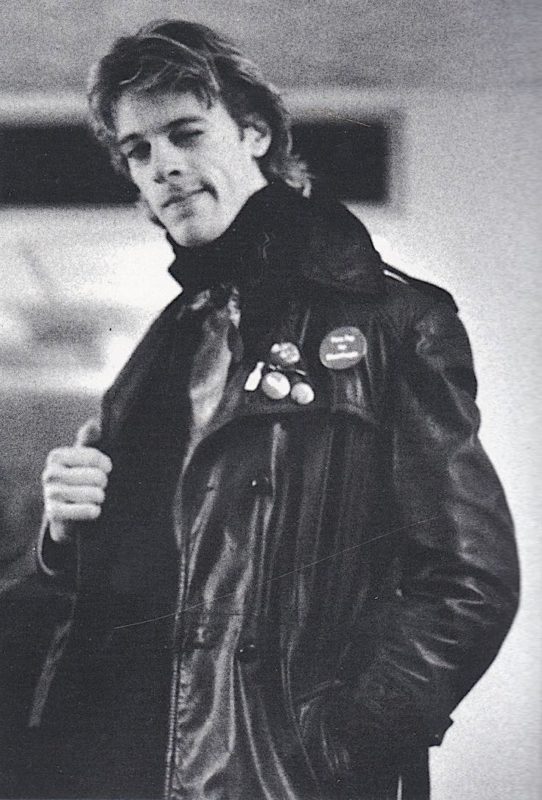

Andy Summers is an artist’s artist. Being ten years older than Stewart and Sting, he had spent a decade as a full-fledged professional guitar player before joining the Police. He is also very prolific and successful in another area of the arts, namely photography, and as the true photographic artisan, almost exclusively in black and white. Throb, I’ll Be Watching You, Light Strings, Desirer Walks the Streets, and The Bones of Chuang Tzu are a few of his publications in that field. Not that Andy is a constant citizen of the ivory tower, but he certainly holds the keys to the place.

A strong leg he stands on is his black humor, and his off-the-cuff, Pythonesque situationism, which shows up in so many interviews and sequences from the 1981 tour documentary The Police Around the World. In Japan, he is taken (by the band and their entourage) to take on a fight with a Sumo wrestler, who is twice Andy’s size and about five times his weight. Andy, of course, gets taken apart, flung around scrotum-squeezingly by his loincloth, and handed back into Sting’s arms like a parcel by the Japanese wrestler. “Well done, Andy, you really held your own!” says an encouraging Miles Copeland, to which a pained Andy quips: “He held my own!”

Having transposed this spontaneous, unpretentious, and relatable approach to life over to the writing of his memoir, it is easy to like Andy Summers as a human and as a storyteller.

Having transposed this spontaneous, unpretentious, and relatable approach to life over to the writing of his memoir, it is easy to like Andy Summers as a human and as a storyteller.

The book is written in flowing prose, and it is a fine piece of pop literature by a very cultured, slightly eccentric gentleman. Full of glorious moments as well as shadows, its center is a love story, which, against the odds, survives the storms of celebrity. One Train Later was the basis for a captivating documentary on Andy’s life, uncaptivatingly titled Can’t Stand Losing You: Surviving The Police (2012).

Just like Sting in his book Broken Music, Andy employs a subplot from which he dives into the past like from a springboard again and again. In his case, it is the afternoon of August 13, 1983, just before going onstage with the Police for the last time, the venue being Shea Stadium (also the last stage graced by the Beatles at their absolute apex, in 1965). Outside 80.000 fans are screaming and holding up lighters. “Like a prayer, it is now, it is forever”, Andy writes, “I strike the first chord.”

Born in Lancashire, in 1942, and having spent his youth on the beaches of the English south coast, dreaming about Spanish guitars and atmospheric photography, he naturally gets sucked into jazz, skiffle, rock’n’roll, and, subsequently, the 1960s youth culture rebellion, which turns post-war Britain from foggy grey to Technicolor, in a way that people like Peter Hitchens will never reciprocate, not to mention tolerate.

Once London gets swinging, Andy finds himself marveling over the Beats and The Tibetan Book of the Dead, as well as losing his trousers while dancing on acid in front of his girlfriend (who justifiably switches sides to be with the Animal’s Eric Burden), playing in a band called Soft Machine, jamming with Jimi Hendrix (on bass!), hanging out with Eric Clapton, to whom he sells one of his guitars (one of the first Gibson Les Pauls in England, soon to be made famous by Clapton), bar flying at legendary London clubs like Middle Earth, Blaises and The Marquee, living on macrobiotic food, Nepalese temple balls and the love that is in the air.

In two shakes of a lamb’s tail, Andy is stranded without money in Los Angeles, after the Animals disband on a derailed tour of the West Coast, and barely keeps himself alive by giving acoustic guitar lessons. In an interview about that difficult period, he says: “Sometimes I would make a hundred dollars – a month!”

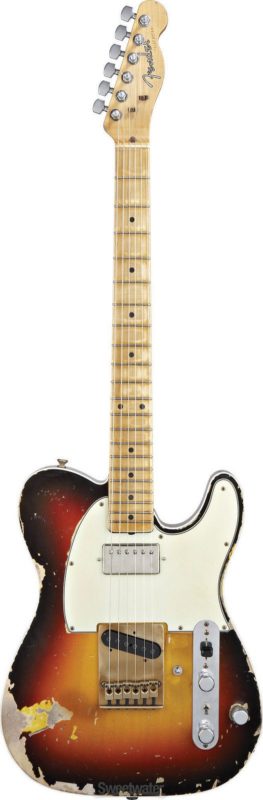

But one day, one of his students sells him a strange guitar, a sunburst 1961 Fender Telecaster with a special something to its sound…

Andy returns to Europe in 1973 as a session musician (for Eberhard Schöner in Germany and on an orchestral rendition of Mike Oldfield’s Tubular Bells, among others) and brings along the Tele that will make history with the Police. In an essay on this guitar, he writes about playing in Finland with Kevin Coyne, in the depths of winter: “We crossed the sea of Sweden with the Tele in the hold of the ship, silent and frozen in its black case.”

After meeting Stewart and Sting, nothing is as it was before. All three guys are speechless after their first jam. This is special – they know it in their bones. Suddenly, the battered and trusted Tele is the hottest guitar in London. After Andy has successfully nuked the first Police guitarist, Henry Padovani (a friend of Stewart’s, who looks a bit like Joe Strummer of the Clash, but can hardly play four chords), the band in its eternal form is complete.

Stewart, in a Q&A, once noted that he remembers Andy’s “job interview” differently. “Andy sat me down at a café one day and said: “Look, Stewart, I think this band really has got something special if you keep it down to one guitarist. And, frankly speaking, I am that guitarist. Also, I always wanted to play in a trio, and: I accept!”

One Train Later takes its title from that meeting, which only happened because Andy and Stewart ran into each other at the same tube (London subway train) station by chance. Chances are, the Police would never have formed if Andy had taken one train later. Also, it is a reference to Andy entering pop heaven one generational train later than his own peers in the 60s.

About the rocket ride to superstardom, the reader will find enough stuff in his book, more than in the other two members’ memoirs. There are episodes galore about the touring life, getting into altercations with a (real) policeman in an Argentinian front row, and going on all-nighters with his buddy John Belushi.

Andy is also the best companion to take you down the rabbit hole of fame, and into the eye of an enormous hurricane that moved through the early 80s.

Not without taking its toll: All three band members were divorced by their wives at the height of their fame (Andy got back with his wife Kate after a four-year hiatus, luckily), and each in his way started to succumb to the Rock’N’Roll lifestyle – arrogance, groupies, coke and hangers-on can take the best man to places from which part of his soul never returns. You are missing out on real life when your own life begins to resemble a Duran Duran video clip.

Also, and famously so, the band imploded on a personal level with Sting becoming the almost exclusive songwriter and calling the shots on the arrangement, recording, and performance of his songs. It was just a question of time before Sting would leave the tight confines of the Police to become STING.

Constant brotherly bickering and power struggles (mostly between Sting and Stew) around mixing console knobs and interview microphones fostered the band’s reputation for being volatile and violent. In those clashes, Andy must have been the go-between and the occasional punching bag. In interviews, he had to fill in the spaces that the other two had left empty, just like in the band’s music.

In the documentary Better Than Therapy (2008), we witness the first rehearsal of the 2007-The Police Reunion Tour, and it doesn’t go well between Sting and Stewart already during the first song. It’s hilarious to see Andy just turning around and walking over to his amp stacks, most probably muttering under his breath: „Okay, here we go again, better get out of the way. Let the younger guys lock their antlers.” Even if the younger guys are already in their fifties at that point.

xx

xx

Andy Summers, like every true artist, is a magician.

His art of conjuring is the alchemy of sound textures, the calibration of tape delay, the combination of his intricate effect processors and stompboxes, the practical magic of chords, in his case, the tricky, “expensive” chords of the classically trained guitarist. Of all the dozens and dozens of shapes he knows on the fretboard, he usually brings the essential ones to the songs he is working on. One special moment that, for me, encapsulates the Andy-Summers-sorcery is that minuscule flageolet break at 2:05 in Message in a Bottle.

Andy Summers is also a consummate traveler. He has been around the world a few times since the Police broke up, on photographic explorations and exhibitions, and as a musician. Even before the Police were a world-class act, they were touring the world guerrilla-style, playing Cairo, Bombay (today Mumbai), Kyoto, and Hong Kong. Andy’s travelogues in One Train Later take the reader to Brazil, the Caribbean, Bali, Sri Lanka, India, and Thailand.

The love for the open road and the big, blue skies reflect in his guitar playing – the clusters of stardust and shimmering plains that are his chords, veering sharply towards the stratosphere.

On p. 96 of his memoir, he describes his early sonic vision: “I never play a chord as a straight triadic harmony but always add another note or two – a suspension or a minor or a major second because it gives the chords an expressionistic and mystical power. A soundtrack to the Himalayas, the sound of deep contemplative solitude combined with the ecstasy of sucking on a pebble and gazing out over the Annapurnas (…).”

One episode is set at the Buddhist temple high up on Swayambhunath Hill in Kathmandu, Nepal, where, among the chattering merchants, monks, and monkeys, he overhears a transistor radio playing a tune by the Police, Voices Inside My Head. A case of synchronicity? Maybe… what goes around comes around.

xx

✺ ✺ ✺

xx

xx

xx

xxxx

xx

xx

xx

xx

BONUS TRACKS

3 x 3 lesser-known recordings, performances, and remixes exemplifying the band dynamics within the Police. Click on the titles to listen in a new tab.

xx

Walking On The Moon (instrumental)

This song took some of its origins in a Munich hotel room on tour in 1979, with a sozzled and dizzy Sting singing to himself, whilst “walking ‘round the room”. As studio cheek lore goes, Pink Floyd had used the amplifier through which Andy’s Telecaster is run on The Dark Side of the Moon, in 1972. Or was it just the echo unit? Nerds, feel free to investigate! And everyone else, please, check out the clarity and panoramic distribution of the three instruments (the echo on the rimshots, the sizzling lead of the hi-hat, Sting’s monolithic bassline that made jazz orchestra leader Gil Evans compliment its composer, and Andy’s two-guitar overdubs), and forget Sting’s charming and childlike lyrics, and his spot-on vocals for once. If that is at all possible…

Shadows In the Rain (live in Essen, 1980)

Andy came up with the swelling verse embellishments only after the song was recorded on Zenyatta Mondatta, the band’s third album. This is the best version I have found of this song from Sting’s cerebral twilight zone. Shadows In The Rain was revived and accelerated for his first solo album, The Dream of the Blue Turtles in 1985, with jazz luminaries like Branford Marsalis, Omar Hakim, Kenny Kirkland, and Darryl Jones, but for me, the essential spell of this song lives in this live recording.

Reggatta de Blanc (live in Miami, 1979)

Fervour, fire, precision: This rendition of Reggatta de Blanc showcases the raw power of Stew’s drumming and the refinement and occasional forceful attack of Andy’s guitar. And Sting going over the rails in ecstasy is a sight rarely beheld in the later stages of his career. You just can’t headbang like this with a lute!

De Do Do Do, De Da Da Da (video)

The state-of-the-art, sloppy video clip of that early MTV period. Three musicians ad-libbing and bad-mouthing after they were (literally) just shaken out of bed by their entourage. Also, Sting is so painfully self-conscious, I can hardly watch the band’s videos (like this one) without cringing. Sorry, Sting. The song, however, is said to be one of Joni Mitchell’s all-time favorites, and it holds up better in 2018 (regarding a plague of social media, fake news, smartphone addiction, and a Twittering US president) with its plea for simplicity and innocence than it did back then. I especially like the oil-can reverb on Andy’s guitar in this original recording.

O My God

From Synchronicity (1983). A blues picked up by the jet stream. Andy’s sustaining off-beat strokes on the verses, his impishly dancing plectrum on the “Further, further, …” part of the lift-off, where there would normally be a chorus. This is all stratospheric stuff. I love Stewart’s precise rolls and Sting’s fretless bass that sticks like hot rubber on blacktop, and his excursions on the saxophone that play you out darkly at the end of this strange pop song about the unfairness and loneliness of the human condition. The quote from Every Little Thing She Does Is Magic (“Do I have to tell the story of a thousand rainy days…”) fits well in the song. The synth-pads (via Andy’s guitar) are a tad too much 80s, but the song still takes away ‘the space between’ for four minutes.

Secret Journey

Another song about the anguish of the soul and the search for enlightenment. No wonder Sting turned to Ashtanga yoga a few years later through a Canadian/Hawaiian yogi and shaman, Danny Paradise. The Sanskrit word guru means “from darkness to light”. Listen out for Andy’s seamless guitar workout and Stewart’s cinematic drumming.

When The World Is Running Down… (instrumental)

Again, concentrate on the mechanics of the instrumental interplay here, without getting carried away by Sting’s postapocalyptic lyrics about James Brown, Otis Redding, Deep Throat, and canned food – all that is left in a corrupted, destroyed world. The Police are futuristic and the first pop band of the space age, in the same way that David Bowie was the first pop singer of the space age. Andy writes in his book about quoting “May the force be with you!” as a running gag in the band, after seeing The Return of the Jedi in a Paris movie theatre. It is no coincidence that movies set in the future, like The Fifth Element and Red Planet both feature When the World Is Running Down, You Make the Best of What’s Still Around on their soundtracks. Also, check out the 2000 house mix of the song by Different Gear.

Voices Inside My Head (Ashley Beedle and DJ Harvey Rmx)

This rework is an awe-inspiring strip down and reconfiguration of a song that was more of a jam or a sketch than anything else in the first place. Also, the sound quality of the single tracks in this remix is higher than on the original record. “Layered harmonic textures, ricocheting with a tastefully applied array of electronic effects — echo, reverb, phasing — to achieve a resonant metallic sound that fills in the wide-open spaces. From straight pop fodder to ethnic boogie to spacey interludes, the Police’s common denominator is still their elastic interplay. They seem determined to keep trying to stretch it. Never have so few done so much with so little. And made it all sound so damn easy.” I couldn’t find better words to describe the sound of the Police around Zenyatta Mondatta (1980) than David Fricke did in Rolling Stone Magazine.

Wrapped Around Your Finger (live in Tokyo, 2008, Stewart Copeland camera)

The lyrics contain references to Faust and the Odyssey. It was part of Sting’s triptych (together with Every Breath You Take and King of Pain) about love lost and power play in relationships on the Police’s last album. This live version from their reunion tour is a treat for percussionists, putting Stewart in the limelight, where he forever belongs as the seminal drummer he is.

xx

xx

xx

xxxx

xx