A FRIEND AFAR

xx

xx

You can not simply call Pico Iyer on a mobile phone. You see, he has never used one in his life.

You can call a hotel somewhere in the world though, and if you are lucky, they will put you through to his room, where he sits on the balcony in the company of three tangerines, an unsweetened cup of Darjeeling tea, and an Edith Wharton novel.

The hotel may be in the vicinity of a writer’s festival in Jaipur or Key West. It may be a lounge in Toronto or Tehran. It may not be a hotel at all, but a landline from a yurt outside of Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia, or a rusty phone booth on the way to Ushuaia, Tierra del Fuego.

You may know that Pico Iyer is one of the great travel writers of our time. However, he is also an expert in the art of stillness, who spends time twice a year in a small Benedictine hermitage above the Big Sur coast.

Born in Oxford, England, in 1957, to Indian parents, both academics in the fields of comparative religion and philosophy, he grew up between England and California, or, as he describes it, “between the middle ages and the future”. He graduated from Eton, Oxford, and Harvard and was a Ferris Professor of Journalism at Princeton from February to July 2019.

Pico Iyer is the bestselling author of more than a dozen books that have been translated into 23 languages. They include international favorites such as Video Night in Kathmandu, The Open Road, The Lady and the Monk, Sun After Dark, The Art of Stillness, and, most recently, Autumn Light.

Since 1982, he has been a constant contributor to Time magazine, The New York Times, Financial Times, Vanity Fair, National Geographic, Granta, and more than 200 other periodicals worldwide. His four TED Talks have received more than eight million YouTube views so far.

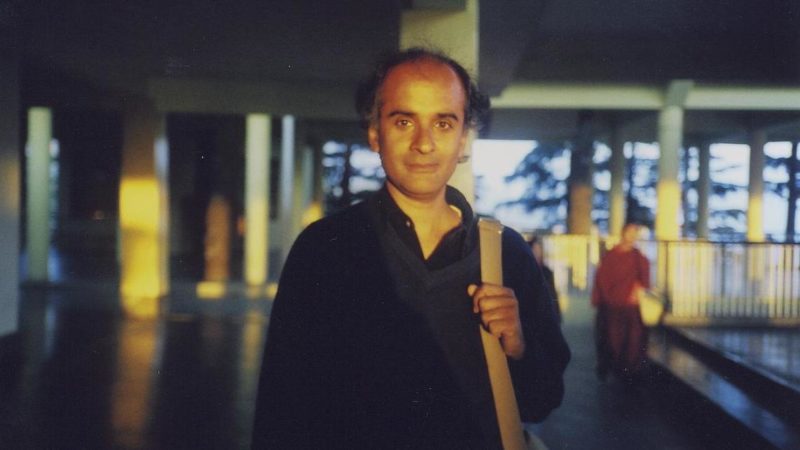

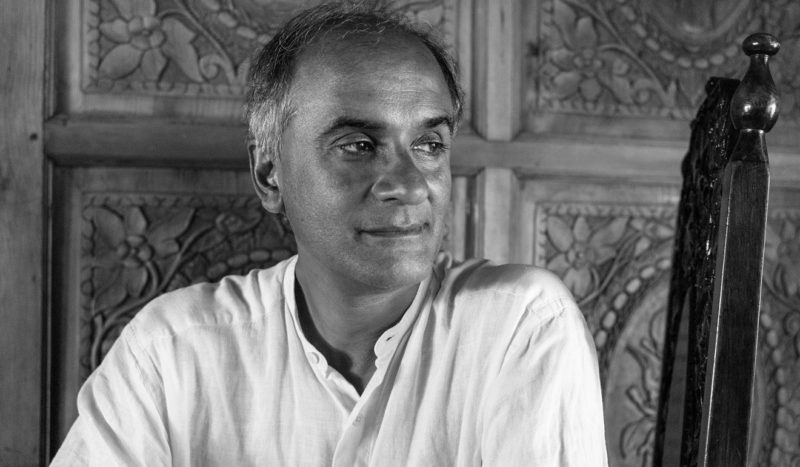

Pico in Dharamsala, 1990s.

Around his 30th birthday, he left his full-time employment at Time in Midtown Manhattan to move to the quiet backstreets of Kyoto.

He had fallen in love with Japanese culture and with a Japanese woman. That way, he exchanged a hectic, urban (and very well-paid) job with writing novels, essays, and reportage at his teenage stepdaughter’s desk, surveilled only by Paddington Bear and her Brad Pitt- and Pokémon-stickers.

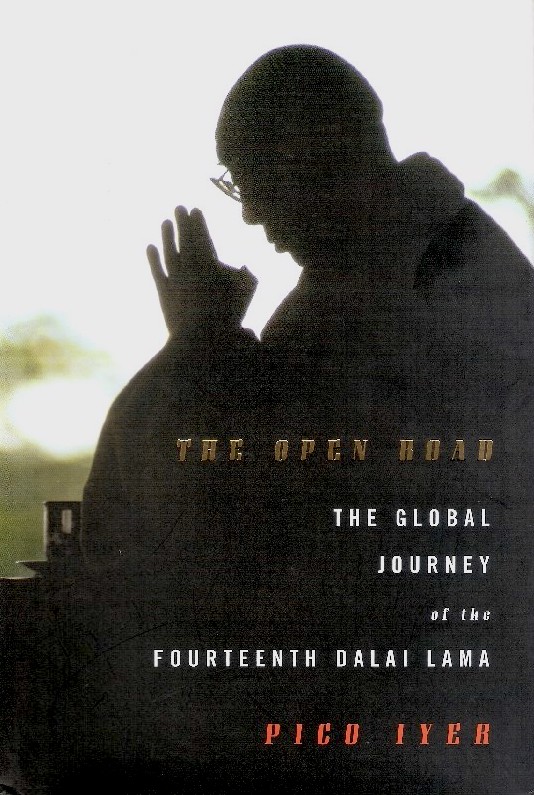

For many years, he was friends with Leonard Cohen and has written liner notes to four of his albums. He has known the XIV. Dalai Lama since the 1970s through his father and is part of his entourage, when His Holiness visits Japan, as he does every autumn.

In 1990, a wildfire burned down the Iyers’ family home near Santa Barbara, California, reducing Pico’s earthly belongings, precious photographs, and the work of years in manuscripts to smoldering ashes. All he now owned was a toothbrush, which he bought at an all-night supermarket.

Today, he claims five suits his own (all exactly the same), as well as a pen and a passport. No further emotional ties need to be established with new material possessions in this life of his.

Pico Iyer has been traveling light, and has, for many people, become sort of a traveling light; spot on, when it comes to world affairs, literature, and the state of the global soul. Constantly on the move, he is a messenger of gods and mortals alike.

Still partly based in Santa Barbara, Pico is married to Hiroko Takeuchi and has been living in Japan since 1988 on a constantly renewed tourist visa. He wouldn’t want it any other way, as it gives him the ever pleasant freedom of being the ultimate outsider, oscillating between polarities, and vanishing in the cracks between cultural stereotypes and lithic definitions like water.

Genial, accommodating, and completely present when in conversation, he is off-the-radar and hard to track down when traveling. To mankind, he remains a friend afar, following his own passions and intuitions. Therefore, he cherishes stillness and silence.

No surprise, Pico Iyer has no use for a mobile phone.

(Simon Schreyer, 2019)

xx

✺

xx

Telling stories in the format of a tale or a song is deeply rooted in motion: The story unfolds as a path, we make prints as we walk. Peripatos among the Greek philosophers and the art of memory in the Renaissance were also connected to walking. You once spoke about doing your best writing when you are away from the desk. How important is it for you to walk the land in order to write?

I think it was the Nobel-price-winning economist Daniel Kahneman (in his book Thinking, Fast and Slow; Ed.) who pointed out from his research that there are certain kinds of things like calculating numbers that are best done sitting down. But other kinds of endeavors like thinking outside the envelope and reconceiving the whole structure of something are done best when we’re in motion.

The reason that walking is so helpful is that I’m freed of the tiny details and I can see the larger picture. Usually, when I am at my desk, my head is quite cluttered. Walking is partly how I clear my head. By clearing my head I am making space for something new to appear.

Where do you set yourself in motion on your walks?

Twice a day I take short walks in our little neighborhood in Nara, Japan. They are usually only about twenty minutes each but that’s when I can make radical changes in my thought. Whereas when I am sitting at my desk and I’m fiddling and trying to make up my mind, I suppose I am really in my linear consciousness.

When I’m walking, the subconsciousness is able to come to the surface more and it allows me to make magical connections that in my conscious mind I could never make. These are the moments when it hits me that I should start the story I am working on at the end or in the middle, or turn those seven sections of the book into four. Or it occurs to me that I should take out the subtitle. That way, I am making changes to the text without even changing a word.

In your first question about walking and the story unfolding like a path, I was also thinking about Werner Herzog. He has this whole philosophy about what happens if you travel by foot. When you travel by foot you set yourself at a human pace, on a human scale. That may have something to do with the pace of our thoughts, which might be why the ancient Greek philosophers found it so fruitful.

Philosophy, poetry, and reading in general can be medicine. Even the Guardian entertains a section called The Book Clinic, where books are ‘prescribed’ to readers in certain life situations. You supply your mother with P.G. Wodehouse novels when she is ill, I heard. Do you recognize the healing aspects of literature in your own life?

I do and it depends on what kind of solace I need. Every day in Japan, I sit outside on the terrace and spend one hour reading a novel or a serious work of non-fiction. I do that to slow my thoughts down, to bring intimacy into my life, and to make myself more attentive and more nuanced. And when I come back inside from our tiny terrace into our tiny apartment, I can feel that I’m a deeper person. It is a kind of daily medicine I take in order to go below the surface of the world. I move from the clatter and acceleration of the moment into a more spacious part of myself.

When friends of mine are in trouble, when they are confused or in a state of grief, I will offer them the book Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind by Shunryu Suzuki, which I think is the most potent medicine I know, in terms of clarity. Just by clearing our heads again, we are reminded that nothing is permanent, nothing is too personal and even if we are in the middle of a storm right now, probably the skies will clear before too long. So, that’s a very particular psychological, or even spiritual medicine.

And for yourself?

I tend to turn to books that inspire me. It could be the poetry of John Keats. It could be the essays of Emerson or Thoreau or the poems of Emily Dickinson. Usually, I would turn to reading when I’m in a state of distraction and I might want to be reminded of my better self. I want to be taken away from the chattering of the world and the news and return to a more reflective person. Reading takes me instantly deeper. It drops me down a well.

There is not a particular book I would turn to. But I would turn to my lifelong literary and philosophical heroes in a way as I turn to my lifelong friends, knowing that they can always be relied upon for sustenance.

xx

xx

xx

“The important things in life we are apprehending through intuition, premonition, emotion, and memory.”

xx

xx

When you were a teenager at Eton, was reading an escape route for you?

Yes! Now that I think of it, it was. Reading has always been both to me, a medicine and an escape. You know, at Eton, it felt a little bit like being incarcerated in that we weren’t even allowed to walk out of the town and we lived within a very strict, almost monastic discipline. Some of the works that I read between the ages of 15 and 17, in my last two years at school, broke me wide open and had an effect on me that very few books have had since.

I think of The Virgin and the Gipsy by D.H. Lawrence and everything about Lawrence, really. He was such an apostle of liberation in England and he had an electrifying effect on me. And then Keats was the other writer I grew to love, especially when I was 16 or 17. His works are deeply romantic and sensuous and thus were about all the things we didn’t have much in our all-boys school.

I also read Hermann Hesse and like so many young people, each time I read one of his books, it seemed to change my life. And of course, boarding schools and medieval monasteries were a subject of familiarity and interest for him too, especially in Narcissus and Goldmund. Even the picture on the cover of the English edition looked a lot like our school and one of the characters, as you know, is a wandering artist.

What did you take away from Narcissus and Goldmund?

It showed me both the merits of the monastic discipline I was being trained in and the merits of the ‘escape route’ to use your words – the very opposite way, the one that Goldmund took. That seemed so personal to me. So many people read Hesse at a young age because he is calling out to their souls to go out on a journey. I felt that call too but in so far as he was rooting the plot in a sort of wintry, Northern European boarding school environment, it really packed a punch for me.

I get a clear sense about you not liking smug aloofness. Does this come from or in spite of going to an English public school?

You are right, snobbish behavior is not appealing to me (laughs). But the beauty of an English public school is that it is really training in irreverence.

In other words, you are rightly surmising that many of my classmates came from quite a privileged section of society. Which also meant that they had no fascination with privilege. We were not trained to become wealthy or successful or to make our mark in the world. In a curious way, we were being schooled in eccentricity and going our own way, for which I am very grateful.

As you may have read I went through quite a hothouse education, meaning I went to some of these fairly high-powered schools and colleges. I think the one good thing about this kind of hothouse education is: You are never impressed by hothouse education again (laughs). You just work it out of your system and see through its deficiencies and then you can move more freely, with perhaps clearer priorities, through the world.

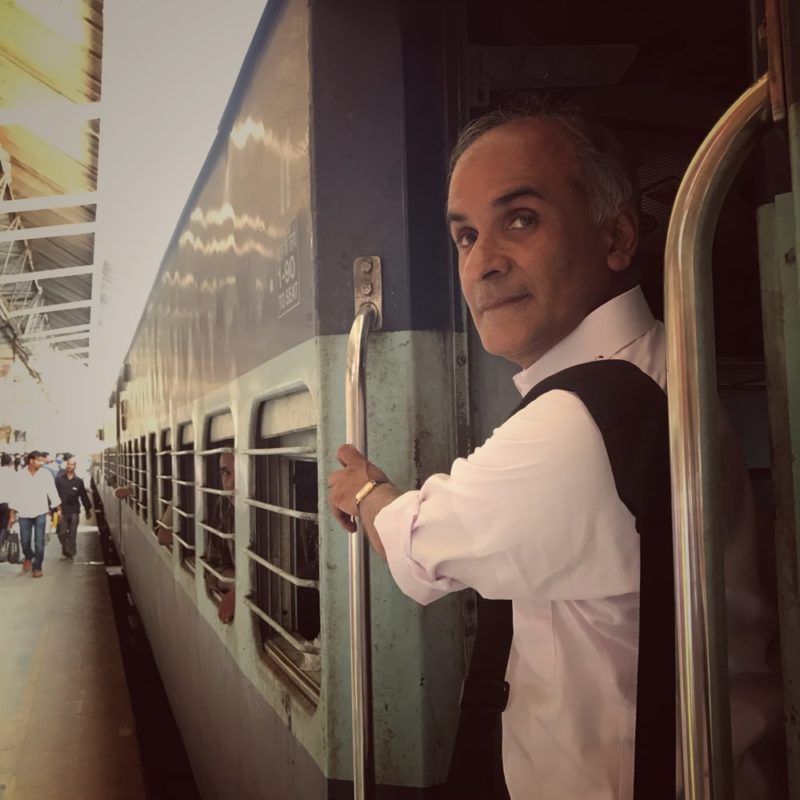

© Sean Lotman

In that sense I would say that Eton was a strikingly unsnobbish and unpretentious place and after I left, I met lots of people who aspired to be something they weren’t and because I went to that kind of school, I was less impressed by them than I might have been if I hadn’t.

One of the virtues of a place like Eton: There are a lot of very bright young boys, there are a lot of very confident boys and there are some quite high-born boys. In such an environment you can’t put on a lot of airs and graces. It’s a good humbling experience. And if you are a very good student, you look around you and there are probably six much better students down the corridor. If you happen to be from a somewhat fancy family you can’t lord it over other people because there are quite a few others from fancy families.

There are a lot of people in England who want to bring about an end to public schools. That will happen and maybe it should happen. But I am grateful to my school for teaching me not to be impressed by external achievements, honors, or titles.

According to John Lennon, an intellectual, male or female, should be the sailor in the crow’s nest, scanning the horizon. I assume that you don’t really like the term ‘intellectual’, but are there any names that come to your mind who fit the description?

You are right about my suspicion of the term ‘intellectual’. Just a few days ago I ran across a sentence from Leo Tolstoy: “Nothing essential is grasped by the mind.” The really important things in life we are apprehending in some different way, through intuition, premonition, emotion, or memory.

It is almost like the mind is making elaborate patterns on the surface of life rather than catching what is beneath it. That is one of the reasons why ‘intellectual’ is not such a happy word.

As to your question about contemporaries who are also visionaries of the future: Thirty years ago, I would have been thinking about someone like Marshall McLuhan, who saw the future, or the horizon, in John Lennon’s metaphor, better than most people…

How high do you rate Zadie Smith’s perspective and view of the world as a thinker and essayist?

Very high! What a beautiful coincidence: Just one moment ago I was going to mention her. One of my favorite essays by her is about Barack Obama, William Shakespeare, and herself, titled Speaking in Tongues. It appeared in her first volume of essays, Changing My Mind, a book that I enjoy almost a little bit more than her recent second volume of essays, Feel Free. I even think it is one of my favorite books of the 21st century so far. It’s an outline for the future and just dazzling in every sense.

My hope for the world as a global person is that we are going to move past binary distinctions and therefore be open to inspiration from everywhere. Zadie Smith, being black and white, can see past our black-and-white-divisions. She can travel high and low and there is no area of life that is outside her reach. I love that you mentioned her because she might as well be the best candidate for looking out of the crow’s nest.

What is it that you admire about her?

One thing I admire about Zadie Smith is that she can write brilliant essays about E.M. Forster and Jay-Z. She knows everything about Joni Mitchell and about George Eliot. Not because she is consciously trying to embrace pop culture and classical culture. I think she just grew up like that. I mentioned D.H. Lawrence a few minutes ago and what’s so special about him is, that he is not exactly male or female, he is not really English or international and he is not exactly high class or low class. He just explores all of that and he is a force of nature, moving through the world, like a ball of fire.

Zadie Smith would be different but what’s remarkable about her is that she knows the world of Cambridge, she knows the world of underprivileged people in London. She knows all the classic books but she also knows hip-hop. It is as if she has taken in every aspect of our world culture, North and South and East and West, and turned it into this beautiful fusion in her books.

I had the rare privilege of interviewing her on stage two years ago. I had high expectations and she exceeded everyone. I found the qualities of her essays in her person: so humble, so open and so eager to learn. Zadie is the rare person of extraordinary intelligence who wants to have new doors opened and wants to be instructed. She is not interested in lecturing about how much she knows but in pushing her knowledge further. I think it’s this combination of modesty and brilliance that is really inspiring in her.

xx

xx

“In Japan, life is about joyful participation in a world of sorrows.”

xx

xx

In your latest book, Autumn Light: Season of Fire and Farewells, you write about your Japanese wife’s family. At the same time, it is a book about the entirety of Japan: Its values, work ethic, ways of communication, and also non-communication. In Japan, citizens are so dedicated to fulfilling their role in society. Wouldn’t it be nice to see, if humans tried to live up to their own nature and personality with the same dedication globally?

The grace of Japan is harmony, community, and people working together and subordinating themselves and their egos in the service of a larger whole.

The challenge of Japan is that there is so little scope for individuals and their freedom and development. In that sense, I would never want to be Japanese, being subject to all the pressures that a Japanese person is. Even though, if I had my wish, I would spend every day of my life in Japan, as a sort of fortunate foreigner who is exempted from these pressures but who can enjoy the best aspects of that culture.

When I first met my wife, who is Japanese, 32 years ago and I wrote my first book on Japan (The Lady and the Monk: Four Seasons in Kyoto), the feeling I got when she looked at me, coming from the West, was that she saw in me a representative of the world of freedom, charting my individual destiny, not being confined by family or social expectations and having the chance to make my own future, which is not something that comes very naturally to the Japanese.

When I looked at her, I saw her as a part of this very disciplined, selfless, and orderly place. And these were qualities that I wanted to learn. It’s no surprise that the Japanese look to other countries for the things they don’t have in Japan, and some of us, like me, look at Japan for things that we haven’t had so much in our life and culture.

I found the scenes in which you play ping-pong with your elderly Japanese neighbors very endearing and also hilarious – especially the old lady who is full of grit and irreverence. Did you place these scenes in the book to counterweight some of the book’s rather sad episodes?

I am very happy that you picked up on the ping-pong scenes and that they made you smile or laugh! And you are absolutely right: I put them in because in a book about things passing, leaves turning and impermanence I wanted to make sure that there is joy and merriment as a counterpoint. Just like in a Shakespeare play, where there are very serious things going on in the foreground, there will be a subplot that is very comical. The ping-pong scenes are like a companion piece for the sadder and more complicated story of the family I am describing.

xx

xx

“November days in Japan have those blazing blue skies. It is cloudless and very warm, even as the leaves are changing colors. It is a mix of radiance and melancholy.”

xx

xx

What do you learn from your ping-pong partners?

The ping-pong club that I am a member of in Nara, is a way for me to remember that there is a real second spring in autumn, as the people I play with are in their seventies and eighties, and at the same time they are carefree children again. Finally liberated from their responsibilities towards Japanese society, they are having a wonderful time and have nothing to worry about. And often, they will defeat a sixteen- or twenty-year-old who comes into the club! It is a reminder that autumn has certain values that spring would envy. One advantage that autumn has over spring is that autumn has the memory of spring inside it and that autumn is the first step towards a new spring.

… Also, it is not the case that spring is all about happiness and autumn is all about regret. It’s more that each has the other one inside it. When I use ‘autumn’ in the book’s title I do so with reference to those November days in Japan that have blazing blue skies. It is cloudless and very warm, even as the leaves are changing colors. I wanted that mix of radiance and melancholy. Just as I wanted that mix of the playfulness of ping-pong with the universal seriousness of family frictions and people getting older.

In Japan, life is about joyful participation in a world of sorrows. Deep down, the world is always moving towards our extinction and the end of things. All of us are getting one step closer to death every day. But precisely because of that, we find beauty in jubilation. Because life has limits we can cherish this moment right now, when I am talking to you and we’re healthy and having a great conversation on a sunny day without a care in the world. I can’t take that for granted because it won’t last forever.

So, autumn is not a sad season, age is not an inherently sad time and I hope that Autumn Light is not a sad book. It is a book on how to put the reality of loss together with the possibility of joy, I suppose. I tried to get that equilibrium right and worked on that little book for 16 years.

In my opinion, the equilibrium works out fine, Pico. I also assume that it must have been a very dear book to write because it’s about your in-laws. The way you were going to portray them is going to stay, right?

That’s right and I am sort of confessing to you that in all those years of writing books, none of them has been translated into Japanese. In this case, however, as soon as the book came out, a Japanese publisher did make an offer and I almost shocked myself by saying ‘no’. I do not want this book to go into Japanese. Partly because I don’t want some of the people I write about in it to complicate their heads by thinking that I am observing them and writing my own subjective accounts of them. Writing it in English, which is not a language that most of the people I described can speak, took a little bit of pressure off me, I hope.

In our Western fear of impotence, and dying is the ultimate impotence, we rarely embrace death. But nobody can give us better advice on what to cherish in life than the dying. I don’t know if you have heard of this survey about the five things dying people regret.

No, please tell me!

Well, the most common thing most of the dying who took part in this survey said is: I wish, I would have had the courage to live a life true to myself, not the life others expected me to live. The second most common sentence is: I wish I hadn’t worked so much. The third: I wish I’d had the courage to express my feelings. The fourth: I wish, I had stayed in touch with my friends more. And the fifth: I wish that I had let myself be happy.

Wow. That’s haunting…The second and the third, I pretty much saw those coming. But the first is extraordinary!

It seems a very complicated thing for people to wrestle with at the end of their lives. It is like a list of things one would put up on the wall to teach one how to live, trying not to be a victim of one of these five regrets. This is really an incredible piece of wisdom.

What I find interesting as well is that none of these ‘five commandments’ (if you turn them around), costs much: You don’t have to be rich to enjoy the moment or the company of friends or to realize your slumbering talents, do you know what I mean?

Yes, it is almost like the subtext of it is: I wish I had spent less time thinking about money and worldly success and more about what would fulfill my heart.

Whenever people ask me why I moved to Japan, I always remember Henry David Thoreau: “I didn’t want to die, feeling like I had never lived”. It was one of the reasons why he went to live at Walden pond because if he didn’t, there would always be this restlessness inside him, something unresolved, a bundle of ‘what ifs’.

I read Walden at a young age and it really stayed with me and made me try to live a life so as to preempt the ‘what if’ and the death-bed regrets.

xx

xx

“I will never forget the first time I was in Tibet, walking out on a terrace, looking over Lhasa. I thought to myself: Not only am I at the top of the world but I am on the rooftop of my being.”

xx

xx

How important do you think is the outlook on the afterlife in shaping life?

As you were formulating your question I could not help but think about how everything is formed by our thoughts. I think we have much more choice and power than we know. And we can choose whether we see something either as an opportunity or a challenge, or either as a loss or a liberation.

Funnily enough, just a few days ago somebody asked me „What’s your notion of the afterlife?“ My answer then was: I don’t really think about it and it doesn’t matter. Because whatever happens or doesn’t happen will happen anyway – or it won’t (laughs). So, I try to concentrate on the Here and Now. But I do realize that I have a lot of power over how my life will go in this next hour and on this next day by tilting my thoughts accordingly.

None of us knows what the death process is going to be like. There have been no reports from the hereafter. It’s a complete mystery. Our fears and hopes are only a projection. One of my friends who is nearly 90 years old once described a near-death experience to me. Like almost everybody with a near-death experience, she came back with stories of light and affirmation. In any case with something luminous, rather than with something absolutely dark.

To quote a thought by Thoreau again, if you start viewing death as a law rather than an accident, it changes your perception of everything. Whether we live and die in fear or apprehension is entirely up to us. Death is not a personal insult or an affront. It is inevitable as the law of gravity. Each of us lives quite happily with the law of gravity, or with the speed limit or other man-made laws around us, day by day. I love that Thoreau quote because everything we say about death is just a construction of our minds.

How has your attitude toward death changed for you over the years?

When I was much younger, I was really scared of dying. Now I am a lot older and I have lived with my wife for more than 32 years, so my real fear is of her dying. What will I do when my right arm is cut off? Because I am healthy and alive but the person who is such an inseparable part of me is gone. Or for that matter, what would I do if I knew I was going to die and she was alone and she would be bereft? In that form, death can be more upsetting when you think of someone you really care about.

I have done two public events with a palliative physician in the United States, B.J. Miller, who has been working for many years with the dying. Essentially, he is an expert on death. He just produced a book, called The Beginner’s Guide to the End. The impression he comes away with is that the process of dying is seldom as somber and bleak as we imagine. When he faces a patient who says “I’ve been given one month to live”, he asks her or him: “What did you always want to do? Ski the Alps or eat six ice creams in one day? Please do that!” It is a different way of coming at the ‘what ifs’.

In the meantime, all we can do, however, is try to be a little kinder, isn’t it? I think it was Aldous Huxley who said something along the lines of: “It’s a little embarrassing that after so many years of research and study, the best advice I can give is to be a little kinder to each other.”

Yes! And isn’t it remarkable how many wise souls emphasized exactly this observation? So many people throughout centuries and throughout various cultures converge on that same point. Novelist Henry James said: “Three things in human life are important: the first is to be kind, the second is to be kind, and the third is to be kind.” Or travel writer Jan Morris, who says that the only religion she believes in is kindness; or in the Dalai Lama’s words: “Be kind whenever possible. It is always possible.”

Since you mentioned the XIV. Dalai Lama, whom you have known since you were in your late teens: I picked up on that story of yours, in which you recount that you spoke contemptuously of Chairman Mao. His Holiness abruptly grabbed you by the arm, chastising you that one can criticize someone’s words and actions, but not the person itself. In the same vein, I was reminded of something the Dalai Lama once said in a lecture on the Buddha Avalokiteshvara whom he embodies: “Extend your compassion to all beings, even to your enemies, even to your own inner demons!”

Hmmm, yes, what a thought! I know that His Holiness’ father was given to anger. He always describes his mother as having been full of kindness and his father as having been hot-tempered. His younger brother, Tenzin Chögyal, whom I know quite well and who is also an incarnate lama has a quick temper and a kind of mercurial personality. What’s interesting is, that whenever he gives a lecture, His Holiness would tell his younger brother to speak on anger – probably because he figures that anger is his brother’s demon.

And when he talked to me about Mao Zedong, the exact sentence he said was: “Criticise the action, not the actor!” Of course: Many deeds are unspeakable and unforgivable, and he has witnessed such deeds but he always believes that there is a possibility for transformation, redemption, and realization.

On several occasions I have had the chance to speak with him about capital punishment, which he will never be in favor of, because even the person who has committed the worst crimes can always have a transformation and we should never assume that they are beyond hope and redemption, to use a more Christian word.

I often think that being too hard on yourself can be as dangerous as being too soft on yourself. I naturally flinch away from people who are always advertising themselves but self-deprecation can be equally a problem, probably. We ourselves need mercy from ourselves.

It probably has a lot to do with the tone and the quality of that voice with which one converses with oneself, wouldn’t you agree?

Yes, I do and I tend to be much too strict with myself. I remember when I wrote that book about Graham Greene (The Man Within My Head), one of the things that appealed to me was that Greene never gave himself the benefit of a doubt. He was always very kind to others but very tough on himself. Of course, that’s a very Catholic discipline, having to do with guilt and self-examination. Now, as we talk, I realize that this can be unhealthy too.

© Brigitte Lacombe

xx

There were quite a few ‘sinners’ or men and women from a privileged background in history who found boundless compassion for all creatures including themselves through retreating into the wilderness or to the mountains. I am thinking of Milarepa or Francis and Clare of Assisi, or your late friend Leonard Cohen living in Mount Baldi’s Zen Center. In Autumn Light, one of the final scenes also takes place on a holy hill. What do mountains inspire in you?

I am very conscious in Japan that mountains are powerful places. I always tell my friends who are visiting Japan that there is an intensity, purity, and clarity about the mountains of Japan that you won’t find even in such beautiful cities as Kyoto. I am somebody who loves to look out over the contemplative plate of the ocean but my wife gravitates toward the mountains. But even so, the mountains have an ancientness and a collective power that strikes me, especially in Japan.

Then there is the hermitage I go to regularly in the Santa Lucia Mountains of California which very much gives me the sense of being able to look at my life from the top of a mountain, from the perspective of eternity or sub specie aeternitatis, as we used to say in Latin. It is a bracing and exciting perspective, looking down from a hill or a mountain. Suddenly everything becomes very small, including yourself, you can see what really matters in life, the larger picture. That is what the mountain offers.

I will never forget the first time I was in Tibet, in 1985, walking out on a terrace, looking over Lhasa and the Potala Palace, the Dalai Lama’s former residence. Of course, there is the beauty and the clarity of that cobalt sky, an altitude of over 3000 meters. I thought to myself: Not only am I at the top of the world but I am on the rooftop of my being. I have had that experience of being on top of my consciousness only once and perhaps it could have happened only in the mountains.

Later I read the wonderful story about this English colonel, Sir Francis Younghusband, who led an expedition to Tibet in 1903/04, slaughtering every Tibetan they met. After he had arrived in Lhasa, he went for a walk in the mountains around the city and came back transformed and dedicated the rest of his life to peace. Another powerful story about the effects that mountains can have on one.

I recently rewatched the documentary Meru by Jimmy Chin and Chai Vasarhelyi, which emblematically represents the Western way of answering the call of a mountain – by climbing to the top of it. In the case of that peak, even to the mythological center of the universe. From the summit, we can enjoy a panoptic vision of everything below. Whereas the Asian mind historically turned toward the mountain from the plane – circumambulating it clockwise, seeing and venerating it from all sides, bowing at certain points, but never even pondering to be so unwise as to climb to its summit. So, is there an Eastern way and a Western way of regarding mountains?

Yes, absolutely, and mountaineers from the West would routinely speak of ‘conquering’ the mountain, while in the East people want to be humbled and put in place by a mountain. By themselves, they would never have tried to put themselves higher than the mountain.

I remember, a few years ago I wrote a long piece for the New York Review of Books on Sherry B. Ortner’s book Life and Death on Mt. Everest contrasting the Sherpa community around Everest and the climbing industry. In it, Ortner writes about the different attitudes of Westerners, or now people from all over the world who pay a lot of money to get the better of the mountain, so to speak, and the local Sherpa people for whom it is a holy place, the Goddess Mother of the Earth. The Sherpa would never want to get the better of the divine.

The same goes for old Japanese paintings: In them, humans are never in the foreground of the picture, or at least they are depicted in a very generic and subordinate way. What you do see is the falling snow and the mountain and these much larger, ancient things. That is also why I like autumn: We come and go but autumn is constantly coming around, reminding us that we are rather small in the larger scheme of creation. We have to bow, in every sense, in front of these much larger forces.

In a presentation of his book The Story of Tibet, journalist and photographer Tom Laird talked about asking the Dalai Lama what the Potala actually means to him personally and His Holiness answered: “To me as a Buddhist monk, it is just a building, a skyscraper made of earth, wood, and gold.” Laird’s next question is a chilling one: “But didn’t the Potala mean the world to the monk who self-immolated in front of it two weeks ago?”

I know Laird’s book and I got so much out of it! I think it captures His Holiness, his gestures, and his way of thinking very evocatively. It’s such a privilege to have the whole of Tibetan history explained and interpreted from his perspective.

I remember the Dalai Lama answering the question about the monk who set himself on fire, something along the lines of: “It’s very sad, especially for his family, but he was hanging on to a symbol rather than to reality.”

Often he tells Tibetan refugees who have just arrived in India: “Take off your Tibetan costumes. They don’t work here in these flat, hot planes.” He wants them to dispense with all the surface trappings of Tibet, as long as they keep the essence of it alive in their hearts. The Potala might be just another surface trapping.

Sometimes when I am traveling with him, people will bring to him fancy models of temples and monasteries and he has no interest in them. It does not matter how golden or how shabby your temple is: The only important thing is what’s inside you. I love that very down-to-earth practicality.

xx

xx

“I am an optimist. The best is yet to come.”

xx

xx

Let us talk a little bit about the down-to-earth practicality of a different sort: the profession of journalism in our days. How are you doing as a freelance journalist in our time of starving newspapers, click-friendly photo stories, and hyper-reduced copy?

Oh, I am suffering hugely! Almost to the point where I can’t practice journalism anymore. I was just explaining to some friends over lunch an hour ago that for so long I was able to live in my boring suburb in Japan and send out articles and manuscripts for books to support my loved ones. Considering the reasons you mentioned, I can’t now. I never thought that the end of journalism would come so soon and so dramatically and abruptly. For me as well as for many colleagues of mine. I would say it’s almost impossible now to survive as a freelance journalist.

Most people I know who have a way with words and a passion for literature and coining good sentences are in advertising now. It seems like so many creative men and women of the arts and letters are forced to migrate into the praising of products and commodities in our day and age. Do you share this impression?

Unfortunately, yes (laughs). Friends I just had lunch with, are all in advertising and I’ll confess a part of me thought: “I wish I had their job.”

I have taken to public speaking to replace journalism as my day job and a source of income. This is a misfortune, because even if I was asked to write a 200-word-article about… let’s say about the samosa, it would be an adventure. I would be doing something I have never done before and I would learn something from the research.

Whereas with public speaking I don’t have that sense and it’s much harder to keep it fresh. However, journalism will always be my passion and my love, and if I meet someone who wants to write, I strongly encourage her or him to have a day job and to write for all the invisible and immaterial rewards, which bring us back to the five regrets on the death bed (chuckles).

How do you react to the editor’s cuts in your books and articles?

There I would make a strong distinction between books and articles.

Articles I have been writing for 37 years now to make a living. I remember when I used to work for Time magazine in my twenties, I was a bit of a know-it-all, I think, and I was a little bit over-confident. So, I would write a piece and my editors, who were very expert and professional at it, would change it. And then I would try to change it back. Later I was embarrassed about this. I was not mature enough to understand the product as well as my editors.

In that sense, I am the employee of somebody else and if they don’t like the article it means it’s my fault. An article is part of a larger package and I failed to give them what they need. It’s like I was working at McDonald’s and I decided to make a piece of sushi instead of a Big Mac. It may be a delicate and beautiful piece of sushi but it’s not what the customer wants. In that sense, if there is a junior editor who completely rewrites one of my pieces, I just try and accommodate his needs.

Books, however, I write to pursue my own private passions. I think of them as entirely personal explorations, almost self-indulgent. A book comes out under my name and essentially every word is there because I chose it to be.

I am very grateful to the copy editors who have worked on my books. They would point out to me that I spelled this one word on page 93 in one way and on page 116 in another way. Or I mention a full moon in October and in fact the full moon was on September 28th that year. They have saved me from so many embarrassing errors and again, I see them as my protectors and my rescue team. The editors who work on my books are only trying to make the book as strong as possible and they are only trying to bring me to my deepest, strongest self.

When I read about the growing nationalism and the predatory greed of capitalism eating up resources and splitting humans up into haves and have-nots, I sometimes doubt if humanity will get it together in time to unite and take concentrated action. Then I reread Whitman’s Leaves of Grass in which he writes in the poem A Passage to India: “The earth to be spanned, connected by network, the people to become brothers and sisters, the races, the neighbors to marry, (…), the oceans to be crossed, the distant brought near, the lands to be welded together.” Do you still think that ‘the welding together of the lands’ is taking place and do you think that A Passage to India (both Walt Whitman’s and E.M. Forster’s) is taking place in our time?

Very much! I’m an optimist and believe that the best is yet to come. About 18 months ago I wrote an essay for an Indian magazine about why I am an optimist. Things are bleak in the United States right now but when I travel to China or India, the lives of so many people are becoming much better very quickly.

And yes, nationalism is on the rise, and people are fighting back against the erosion of boundaries. But I think nationalism is on the rise because it’s on the run. We are seeing a lot of strongmen and nationalistic governments right now but more and more people are extending their hands across the boundaries of race and religion.

It’s so fitting that you mentioned Walt Whitman because only a couple of days ago a friend in Singapore pointed out to me how similar Whitman is to Leonard Cohen. This makes sense because they both were speaking to the same vision. And since you mentioned Forster: I went to Varanasi in 2016 to take part in a documentary based on A Passage to India. I had read that book two or three times previously and never really liked it and neither did I really like Forster. I found him a little too tame and confined for my taste.

But when I read it most recently, I was overwhelmed and I thought that it really was a brave and remarkable book. What I loved about it most was his humility in the face of mystery. I feel over and over that the culminating idea behind that book is: There is no explaining the forces around us. There is a darkness here I can’t put a name to and I can’t begin to understand. But it’s there.

In that regard, it reminded me of Paul Bowles’ The Sheltering Sky. An important component of travel is being confronted with this huge enveloping vastness that can take away your soul. Something that, if you were sitting at home, you would never be aware of. In a way, it was a remarkable act of courage for Forster to put himself out there and voice that feeling.

Some of the thoughts in that book about whether people can become friends across the borders of race, he goes on about back and forth quite a bit. But what I loved was that he caught something essential about India: That untameable force that broods outside in the jungle caves and in the sky. That’s a tonic idea to confront because it reminds us, once more, of how small we are.

In terms of the framework of your question: Children of my stepdaughters’ generation don’t think very much along the lines of race and nationality. Just last night I was talking to a group of students from Singapore and began to explain that I am the son of Indian parents, born in England, and I grew up in California and now live in Japan and so on. Quite soon, one of the graduate students said to me: “You’re using such outdated terminology, you’re thinking in terms of nation-states. I don’t think that works anymore.” And I was so happy for him to say that! Even the term ‘multiculturalism’ seems to be from an outdated lexicon to them.

Soon, a befriended couple here in our little town will have children. Those kids will be of Tyrolean, Bavarian, US-American, South Korean, and Viking descent. Is it these kids that are the welding junctions tying the lands together?

Exactly. I think it was in the New York Times that I read that in 1958, 87% of Americans disapproved of mixed-race marriages. By 2014, that same number is 3%. Whenever I go to major cities around the world, every other couple belongs to different cultures. That wasn’t the case 20 years ago. And their children, just like Barack Obama and Zadie Smith, as well as your friends’ children, are going to be harder and harder to pigeonhole in one race or culture.

The reason why many people on the right are so unsettled by this is that they can see that the world is moving more and more in that radical direction. I often cite a woman I met in California, who said to me once: “Maybe I wasn’t thinking so well about Islam, but suddenly my daughter marries a man from Iran and suddenly I have a granddaughter who is Islamic. How can I hate my granddaughter?”

When I grew up in England, society was very black-and-white and racist. Now the average person you meet in London was born in another country. Of course, London is quite different from the countryside around it. But the world is becoming more and more urban and colorful. That’s one of the most exciting developments in my lifetime. Whatever I wrote in The Global Soul in 2000, I feel that the world has accelerated in that direction beyond my expectations.

xx

xx

✺ ✺ ✺

xx

xx

xx

Books by Pico Iyer

xx

Video Night in Kathmandu: And Other Reports from the Not-so-Far East

The Lady and the Monk: Four Seasons in Kyoto

Falling Off the Map: Some Lonely Places of the World

Cuba and the Night (Novel)

Tropical Classical: Essays from Several Directions

The Global Soul: Jet Lag, Shopping Malls, and the Search for Home

Imagining Canada: An Outsider’s Hope for a Global Future

Abandon: A Romance (Novel)

Sun After Dark: Flights Into the Foreign

The Open Road: The Global Journey of the Fourteenth Dalai Lama

The Man Within My Head: Graham Greene, My Father and Me

The Art of Stillness: Adventures in Going Nowhere

This Could Be Home: Raffles Hotel and the City of Tomorrow

Autumn Light: Season of Fire and Farewells

A Beginner’s Guide to Japan: Observations and Provocations

xx

xx

xx