Learning by Heart

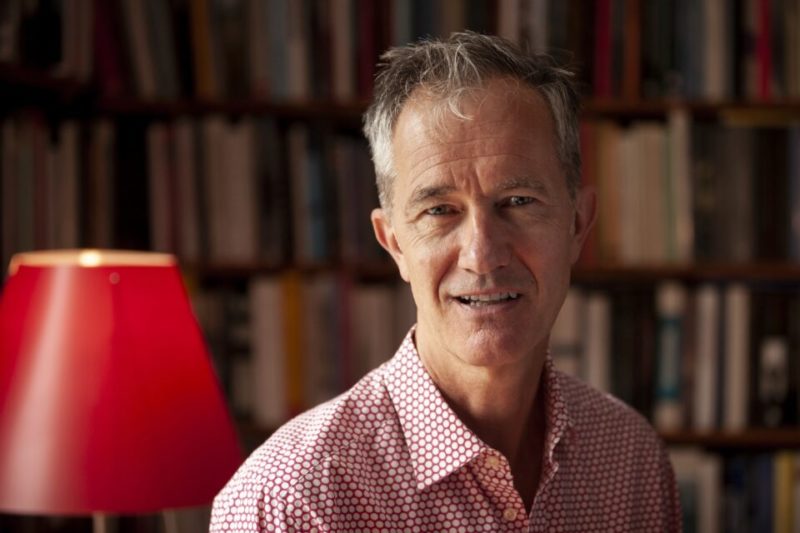

A casual conversation with English writer Geoff Dyer on the occasion of the publication of his memoir Homework, in early summer 2025.

While a cross-European thunderstorm unleashed its power, we serenely cruised through literary lagoons and the topical landscapes of films, books, bands, England in the 1960s and 70s, the ethos of the working class hero, burning impatience, the joys of funky techno and armchair mountaineering, his dislike of Rolex watches and Bruce Chatwin, as well as sponging glamour off Daniel Kehlmann.

Attentive readers of Geoff Dyer’s work will notice the silent omnipresence of two of his polestars: Nietzsche and Lawrence. Only once did we interrupt our flow of thoughts, when Geoff had to let the almost Shakespearean words ring out to his wife: ‘Rebecca!!? It’s raining! Can you shut the landing?’

by Simon Schreyer

Hello Geoff, nice to speak with you. How are you handling the heatwave in London?

It’s not only hot, but it’s the worst kind of hot: It’s cloudy, and it looks like rain the whole time. Heat without sun is no good at all.

I agree. After ten years of living in sunny Venice Beach, L.A., and teaching at the University of Southern California, you and your wife just moved back to London, North Kensington, I understand?

Yes, but let’s call it Ladbroke Grove because anything with the word Kensington in it sounds so dreadful.

Dreadfully posh, you mean?

(Laughs) Yes, it really does. We’re right at the heart of where the Notting Hill Carnival takes place every year, and it’s so great to be back! We moved here on the 8th of May, and on the 10th and 11th of May, my favourite band in the world, the Necks were playing a four-show-eight-set residency at the Cafe Oto in Dalston.

That’s what I call perfect timing. Have you transported your library back to England from California yet?

The bulk of it is bobbing on a container ship somewhere in the middle of the Atlantic.

Is there anything interesting for the German book market that’s coming out in translation from your back catalog? And are you still with Dumont or with another publisher?

I’ve really got no idea. The German market has been a frustrating place for me. Back in the 90s, I kept hearing of these English authors, some of whom I had very little respect for, who were getting German publishing deals and selling huge quantities of books. I wasn’t published in Germany for a long time. Eventually, I was, but I’ve never had any success at all there. The books have appeared in translation, but the millions of pounds I was expecting to flow into my bank account – that’s never quite happened.

…..So my only claim to fame in Germany is that I’m friends with Daniel Kehlmann, and that does seem to endear me to the people of Germany and Austria. I stayed in his apartment in Vienna, which was apparently Stefan Zweig’s apartment once upon a time. When I say I know Daniel, people react as if I was saying I was a friend of Goethe’s or something.

The last book I read before your most recent one, Homework, was your first novel, The Colour of Memory, set in London in the early 80s. Homework is a memoir about your Cheltenham childhood in the 1960s and 70s. It probably would be frivolous to call it a non-fiction prequel to the fiction of The Colour of Memory, but it ends where the other book starts, right?

Not quite, as there’s the gap of the Oxford years. That’s the missing bridge between Homework and The Colour of Memory, and that’s no bad thing because it’s pretty well impossible to do an Oxford novel. It’s so drenched in cliché that I don’t know how anyone could pull that off now. That’s one of the reasons why there will definitely not be any more volumes of memoir. It’s very difficult to get out from under the shadow of these Oxbridge novels like Brideshead Revisited by Evelyn Waugh or Maurice by E.M. Forster.

…..But you said it was a frivolous comparison, whereas I think it’s a pretty good one: that this is the prequel to that.

Was spending time in your childhood a rejuvenating experience in some ways, or did you occasionally feel like “a tourist of your youth”, as Sick Boy accused Rent Boy in Trainspotting 2 ?

(Chuckles) Oh, this is already great fun. I don’t know if it was rejuvenating, but I’ve certainly felt closer now to my 15-year-old self than I have for, God, 50 years or something!

…..But in another way, it’s not rejuvenating because at some weird level, one remains that person, of course. I have exactly the same DNA as the person I was at that age. The weird thing is that despite all these changes you go through, you remain the same entity. Which is one of the reasons I’ve chosen that quotation from King Lear that introduces the little section at the end of Homework, called “Jerusalem” after the song, or poem, where the Earl of Gloucester says something along the lines of ‘I think you’re changed in the way you speak.’ To which Edgar answers, ‘I’m changed in nothing except in my garments.’

…..Expanding on this a little, I think of Bruce Springsteen when he became very famous, a true megastar. People complained that this billionaire rocker was writing songs about a guy working in a garage. Springsteen countered that the experience he had as a kid was so foundational to who he is that it’s a very easy place for him to reach—he’s never left that old self behind.

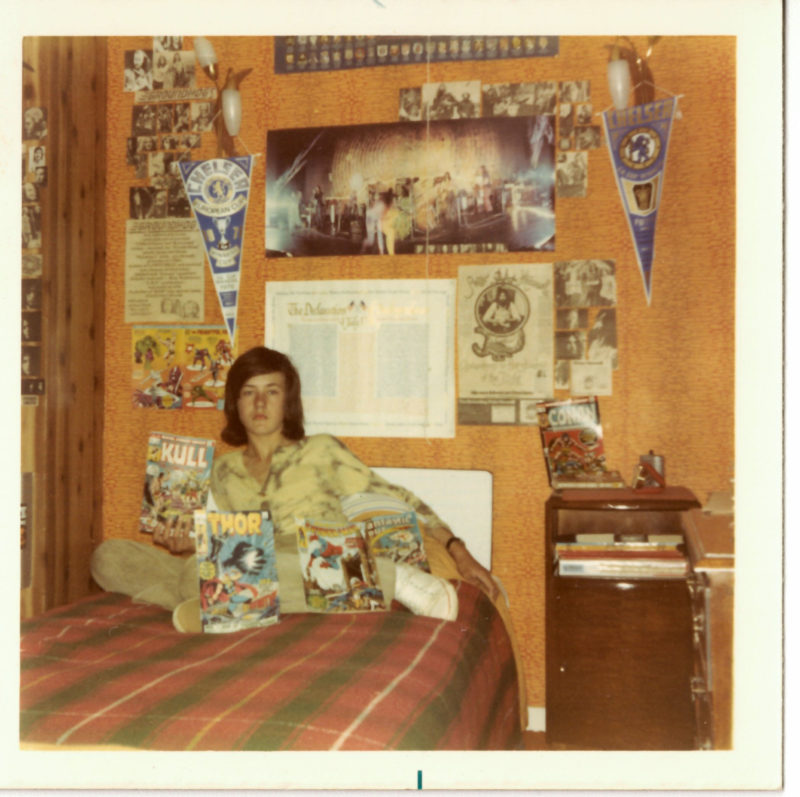

Games seem to be a foundational experience of yours in Homework. You took games and playing seriously serious from an early age, collecting Action Man figurines, bubblegum cards, posters, and building model planes. As for the latter, I was surprised to learn about your lack of diligence and accuracy in your early Airfix stages.

Well, it was because I was learning how to do them as I went along. Those instructions that you got on the packet, they’re a precursor of the instructions you get when you buy an ‘easy to assemble’ IKEA box of a shelf or a cupboard. Soon it turns out that what seems very straightforward is full of all sorts of unexpected complications, and if you do one thing out of sequence, then it all goes wrong.

…..By a certain point, two things had happened: I’d acquired mastery of the grammar of those mainly visual instructions, and I’d learned the practical skills of how to assemble the model airplanes. The one thing that never went away was a sort of impatience, which has continued to manifest itself during my botched attempts at DIY, putting up shelves and cupboards in the house.

You describe yourself as possessed by a burning impatience. I was reminded of the title of that Antonio Skármeta novel, which would be a noble quality to cultivate: Burning Patience.

Very good. Well, I’m in a line of work where you need a great deal of patience. You can sort of hurry a bit at some stages of writing. It’s no bad thing to just write stuff down without too much regard to spelling and all this kind of stuff. But at some point, you really do need a great supply of patience. That’s very, very necessary. Is it Gustave Flaubert who said that ‘talent is a long patience, and originality an effort of will and intense observation’?

…..I have a great fondness, since we’re speaking of patience, for a line of D.H. Lawrence’s, who means so much to me. He said: ‘When I was young, I had very little patience, and now that I’m old, I have none at all.’ Although, of course, Lawrence’s idea of being old was itself a symptom of impatience because he was actually young when he said this. On the other hand, I suppose he was old in the sense that he died aged 44.

…..But yes, at a certain stage in writing, you need to be able to apply yourself without any eagerness for it to be over with. You need to be completely at one with what you’re doing, and that is a state of bliss.

“Everything that makes you happy in life is the opposite of exclusive.”

You showed an early talent for being artistic, which your working-class parents ostentatiously were not. I’m talking about the photo collage at your grandfather’s funeral, onto which you taped lines from King Lear. Your parents’ reactions to this art piece were slightly underwhelming. Was that because, for them, a death in the family was so private that it shouldn’t be put into a larger cultural context?

The word I use is ‘inappropriate’, and it’s not because it’s a private family matter, but it’s more that this whole realm of quotation or anything like that was so completely out of keeping with the natural communication style of my family. To them, it seemed like showing off. I mean, the whole idea of the literary was inappropriate.

…..Two things happened, really, which are at the opposite end of the linguistic scale: I mentioned in the book that my dad never swore. As I became more highly educated, the house was suddenly filling up with profanity and obscenity. That was horrible to them because, well, it just was! So on the one hand, their son’s form of speech was becoming debased, and on the other hand, it was becoming more elevated with all this stuff from Shakespeare and so on.

…..Anything outside the domestic register of the home was either inappropriate or offensive.

Was it also an attempt of yours to get a little bit more literature into life?

There was very little active attempt and very little agency on my part. I was an almost entirely passive beneficiary of this educational system that I went through, and gradually my head started to fill up with literature, so it just sort of happened. It was passive, partly because at a certain point, doing schoolwork ceased to be an obligation and became something that I took great pleasure in. Now, for someone like my wife Rebecca, whose father was a historian and whose mum was a piano teacher, literature was a part of her life from an early age. She read Great Expectations when she was nine or ten.

Your collage and your parents’ reaction made me think of that Oscar Wilde line, ‘If a man treats life artistically, his brain is his heart.’ Would you agree?

I would disagree with this, because I think through literature and poetry, the heart itself is changed. My experience is similar to that of the Texan writer Larry McMurtry (Lonesome Dove, The Last Picture Show, e.a.). He was brought up to run a cattle ranch and worked as a cowboy, for which he had no aptitude. Then, famously, one of his cousins left him a box of 19 books, and his life from that point on was devoted to books: accumulating books, reading books, and writing books. Book ranching, as he called it.

Like McMurtry, you grew up in a house without books. Was it your late discovery of books that started your unexpected and long love affair with literature?

If you grow up in a house without books and then you discover books, or the other way around, when books discover you, then that’s one of the most privileged relations you can have to literature. Suddenly, this whole world opens for you, and that’s a wonderful thing.

…..There are so many passages from my favourite authors that I have learned by heart. That’s the idiom we use in Britain: We learn something by heart, not by brain, and if you learn it by heart, that means it becomes part of your bloodstream, part of your purpose, and part of who you are. I can’t read the end of Paradise Lost without starting to cry because that’s the effect it has had, not on my brain, but on my heart.

Your mother Mary, a school dinner lady from a Shropshire farm, and your father John, a Gloucestershire sheet metal worker, are, of course, the heroes of your book, although they would have cringed at such a thought. They were decidedly ‘anti-glamorous’ by background, I think that’s the word you use?

Yes, my parents’ lives were distinctly unglamorous and always very frugal. They led a life of subsistence existentialism, or existential subsistence. This is not surprising for people of their generation who grew up in the 1930s, a time of great scarcity. Then came the Second World War and its aftermath. It’s something that I’ve been talking about in America, where I’ve been on a book tour recently. There, they forget that rationing in Britain continued well into the 1950s.

Your parents come across as really endearing, humorous, and very warm in your memoir, with a sort of modesty reminiscent of the parents in Lawrence’s Sons and Lovers, which you allude to in Homework, or of the grandparents in Ozu’s 1953 film Tokyo Story.

Right, yes! My parents were very like that, and I’ve inherited many of their qualities and values. Update the language a bit, and what might have seemed like stinginess, now we’d call it ‘sustainability.’

…..I’m very glad that I didn’t turn out as one of those people concerned about status, who think it’s essential to get the new iPhone the moment it comes out. Whenever I see anyone wearing a Rolex, I think, ‘You fucking twat!’ Especially since as soon as you’re wearing a Rolex, then part of you is frightened you’re going to get robbed. So you walk around in a way showing off your wristwatch, but you’re also showing off your fear.

…..On the rare occasions when I stand outside a Gucci or a Dolce&Gabbana store, I feel that these places of heightened expense are really places of cheapened value. I guess that all comes from my parents. Although in the interest of absolute honesty, I have to say that I do have one weakness for luxury brands, and that is for Freitag bags.

Well, okay, but since they’re tailored out of weatherproof truck tarps, they are almost working-class items, aren’t they? Probably even Bruce Springsteen owns one.

Well, not quite. They’re expensive, and I’ve got a lot of them. But as you get older, there are so few things that are worth having.

…..I’m always amazed at these very wealthy people who keep wanting to get more wealth. And I think, what on earth can you do with it? We’ve been living in Los Angeles for all these years, and now we’re back in London, as we discussed at the beginning of our chat. Many aspects of being in London make me happy. Nothing makes me happier than the way that we don’t have to have a car here. So, to me, the idea that anyone could want three cars is just bonkers. I hated even owning one car because it’s so much stress.

…..Anyway, so much of this is insane if you think of the way that a restaurant or a resort is advertised as being ‘exclusive.’ It requires two seconds of thought to make you realise that everything that makes you happy in life is actually the opposite of exclusive. It’s always a feeling of being included, of inclusivity. It’s such a simple thing to learn, but instead, people buy in, quite literally, to this idea of exclusivity, which is making them isolated and unhappy.

The class photo in Homework is an extraordinary picture. It’s like something out of Whistle Down the Wind. All the kids’ faces have so much character.

Yes, and what I find incredible about this picture is the way that class has entered the children’s DNA; it’s in their faces. So different from, let’s say, if you saw a picture of kids the same age from the same period who were at Eton or Harrow. Also, I feel that this picture proves something that I claim at the beginning of the book, which is the proximity of the Second World War. That picture looks so close to and so formed by the Second World War to me.

At the same time, the ‘Sixties’ are looming on the cultural horizon, aren’t they?

Well, although we think of the Swinging Sixties as a nationwide phenomenon today, a lot of life in Britain remained, as it were, in black and white. That famous burst into colour that we know from watching documentaries about the Kinks, the Who, or the Rolling Stones didn’t happen until later, and it was certainly a long time before it spread geographically from some pockets of London to my part of England.

How did the first Beatles and Stones songs hit you? Were there some favourites among them that you picked up on?

The Beatles were a big thing when we were little kids. Of course, we collected all the merchandise and enjoyed the songs. But really, after that very childish kind of phase, the Beatles have meant absolutely nothing to me. I can’t imagine ever listening to a Beatles song on my own, and I always take umbrage when people speak of Dylan and the Beatles in the same breath.

…..The Rolling Stones, of course, I quite liked at the time, and they are without question amazing. I only really got into the Stones much later, at university and after. Now I watch films like Gimme Shelter, and I can see their great power, but they weren’t an active presence in my childhood.

…..Nor was Bob Dylan. I didn’t get into Dylan until Desire came out in 1976. So there was that early pop thing when I was a kid. And then there’s a gap until the dawn of harder rock, of prog rock, really, in the 1970s.

How about Pink Floyd?

No, Pink Floyd, never. There was just that one track on their 1971 album Meddle that I quite liked, that (beatboxes the snarling, metallic bassline from One of These Days): dada-di-deng-di-deng-di-deng. . . By then, some of the more lavish works of Pink Floyd were sort of the beginning of the end of prog. That was the moment when progressive rock started to become regressive, and I was falling out of love with it.

What did you like about your favourite prog bands like Hawkwind?

I liked that driving, repetitive, not-too-orchestrated aspect, which I realise now they got from Krautrock, of course! Can, I think now, are a band of genius, but when you’re a kid, you tend not to know where things come from. You don’t realise who’s taken what from whom, so I was completely unaware of just how indebted some of those Hawkwind tracks are to something like Neu!.

…..Even now, I love music that’s long form and repetitive, with a hard groove and not too much elaboration.

Did reggae and dub records make it onto your turntable? Too slow for Geoff Dyer?

Much too slow, you’re right. And maybe there was a racial element to it. Maybe it was too Black, and it wasn’t until university and, of course, living in Brixton in the years after that I really got into reggae. Also, because I hated smoking cigarettes so much, I was a very belated convert to the pleasures of smoking marijuana. It took me ages to get the hang of it. It wasn’t until the discovery of water pipes in Brixton in the 1980s that I got into Jamaican music, and it certainly enhanced my experience of listening to heavy dub and reggae.

And what about punk and new wave?

When I was at Oxford in the late 70s, like everyone, I got into punk. One of the things that always amazes me is the power of punk. Let’s suppose there’s a program about the Sex Pistols on TV tonight: Wow! The power of that music is absolutely undiminished all these years later, and it’s an assault on everything that had gone before! I certainly got into that, but it was a brief moment, punk, actually.

…..The thing that followed on from that, new wave music, was the main era of concert-going for me. So I saw all the great new wave and post-punk bands in London: Echo and the Bunnymen, Gang of Four, I saw the Clash three times, the Jam . . . I mean, look, it would be quicker to list the bands I didn’t see. I never saw the Talking Heads, which is a shame. I did like the Police, even though I could see it was all a bit blanded out and I lost interest in them quite quickly, but I saw them at a festival in France in the summer of 1980, the year after leaving university. That was a phase when I was going to gigs the whole time.

After your explorations of jazz, which you got into in the 1980s and wrote about in But Beautiful, you turned to electronic music and clubbing. How did that Bristol scene around the Wild Bunch, Massive Attack, Tricky, and Portishead strike you?

Yes, I came to love jazz, world music, ambient music, and also chill-out with that whole Bristol scene. Massive Attack I loved, although I have never seen them live. I first encountered them through their remix of that track, Mustt Mustt by Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, a Pakistani singer who I saw in London at his absolute peak in 1990.

…..It’s funny, gig-going, isn’t it? Even now, you meet people in their 70s and 80s, and they still remember the night they saw Jimi Hendrix as one of the validating nights of their lives. I can remember concerts like that, and Nusrat was certainly one of them.

…….But if we are talking about club-going: While I was going out in the 90s, I really did like uptempo dance music. My favourite kind of dance music was house music, of course, and what I loved was funky techno, and that continues to be my favourite. I mean, it’s got to be funky techno because the funk retains the all-important Blackness of techno.

…..And sometimes at that famous nightclub Berghain in Berlin, let’s say, I felt it was just too regimented. As a result of that, it stops being a party, although I know all sorts of debauched things happen there. Also, everyone is dressed in black, and that gives a rather grim quality to a nightclub, I think.

“The biggest changes are happening not just gradually but imperceptibly.”

Let’s stay on the grim side for a moment: I want to address your intense dislike of Bruce Chatwin. On one occasion, at a lecture or in an interview, I thought I heard you mention his book on Wales, On the Black Hill, favourably. Did I misunderstand you?

I did like On the Black Hill, you’re right. I could hardly detect the fingerprint of Chatwin in that.

…..Sometimes you read a book and you take such a dislike to the authorial presence, and that happened to me reading Chatwin’s so-called masterpiece The Songlines, in which he would have all these encounters with Australians, and then he’d emerge looking so much cleverer than they were. Made him seem like a dick.

…..And then he was famous for having these ideas, and he never seemed to me a great purveyor of ideas. Even though I never actually met the person, I took against the authorial persona tonally and personally. I feel as a writer you should always emerge looking worse than anyone you have encounters with.

Another writer you don’t particularly value is Henry Miller, but I recently reread his Big Sur and the Oranges of Hieronymus Bosch, and still liked it. What’s your assessment of him?

Henry Miller is one of those writers I think I should probably have read when I was a lot younger. I’m not patting myself on the back saying this, but of course, the sexual politics of it have not worn well. He was poisoned for me by my reading of Kate Millett. I read Millett on Miller before I read Miller himself.

Did you take many trips to Big Sur when you lived in California? Is that mystic coastline a landscape that fascinates you?

Yes, I absolutely adored it when we used to visit California from England. Highway 1 was a drive that I had always wanted to do, and in fact, did many times, particularly in the last century. During the early years of this century, I was crazy about going to Esalen because I was so into psychedelics and all this sort of stuff, but never went there.

…..Anyway, so from 2014 until recently, we were living in Los Angeles, really easy to get to Big Sur from, except it turned out to be impossible to get there. Highway 1 has been closed consistently because of either rain or fires, or mudslides, so in a way it’s proved to be more difficult to get there from Los Angeles than it had been from England!

…..However, we did stay a couple of nights for free at one of those famous resorts, the Post Ranch Inn, because I wrote a piece about it for The Times in 2015. That was a fabulous experience.

I imagine you high up on a hill, surveying the ocean and watching the weather change. And that brings me to your fascination with gradual change, like the Skyspaces of James Turrell, the meandering of Andrei Tarkovsky’s films, and also the slow, sonic metamorphosis of the Necks’ music . . .

Hooray! Yes, exactly: Nothing much is changing, and then within 20 minutes you realise you’re in an entirely different sonic landscape than you were 20 minutes ago.

…..That fits in with something else I mentioned in The Last Days of Roger Federer: And Other Endings, and that is my dislike of books or films where they say, ‘it was an afternoon that would change their lives forever.’ I’m a great believer in the biggest changes happening not just gradually but imperceptibly.

I read in a Guardian article of yours that you regard Free Solo as one of the best films ever made, period. Are you an armchair alpinist?

Indeed, I do, and I’m absolutely an armchair alpinist (laughs). Maybe not so much an alpinist, but an armchair climber of the hot mountains of the world, as opposed to the snowy, cold ones. I love that stuff! I could watch it endlessly. I heard that they were going to release a real-time, four-hour version of Free Solo with only the climb, which I would happily watch because the aspect of the film I didn’t like is the tension between Alex Honnold and his wife, who wants to stop him doing the thing that ontologically defines him.

…..This is the greatest time there’s ever been for mountaineering films because of the technology.

The cameras have become so small, light, and still technically so advanced. You can take them anywhere and bring back incredible footage from places that most of us could never visit.

Yes. But in terms of the Alps, or if we take it to a more extreme zone, the Himalayas, or K2: Rather than seeming attractive, the actual alpinism must be such misery, sitting in your tent waiting for the weather to clear and probably having to dash out to the toilet because you’ve got altitude-induced tummy troubles. That seems an utterly wretched way to spend your time. Free Solo I loved because it was a snow-free rock climb you could do in your shorts.

I recently watched Paolo Sorrentino’s 2015 film Youth (La Giovinezza). It’s set in a kind of Magic Mountain hotel. The main characters have completely different attitudes towards their late work in one case and their last work in the other. It seems like a companion piece to The Last Days of Roger Federer, and I wondered if you had seen it?

Interesting! I haven’t seen it, but I’ll watch it because I really loved La Grande Bellezza. Some people accuse Sorrentino of being too derivative of Federico Fellini, but I felt that wasn’t even true of La Grande Bellezza. I thought he was bringing something else to it. The obvious Fellini-like scenes are some of the weakest bits in that film, I think.

I would like to read two lines to you. One is by Tolstoy, quoted in an interview with Nabokov: ‘Life is a tartine de merde (a shit cake) which one is obliged to eat with little spoonfuls.’ Nabokov answered, ‘Well, he was quite vulgar sometimes, the old boy, wasn’t he? My life resembles fresh bread with country butter and Alpine honey.’ This ties in well with a quote of which I’m not sure if it’s by you, or by Zadie Smith, to whom it is frequently attributed on Instagram: ‘Life is so horrible you wonder how you can be happy for only one moment. At the same time, life is so wonderful that you wonder how you can be unhappy for only one moment.’

You’re absolutely right, that is me, not Zadie Smith. How unjust the world is (chuckles).

…..Yeah, I guess I lurch between the two experiences, and it extends in all sorts of ways. For example, today, and generally, I feel great! I’m 67. I’m in great shape. But last November, I was preparing to give a lecture in Florence, and I wasn’t even in the gym; I just got up from my desk in an innocuous way, and my back went. At that moment, and for the next three weeks, I went from being a fit and healthy 67-year-old to feeling like I was 167 years old. So it can all change very quickly.

…..The key thing is that Nietzschean idea that I like to commit to: the Eternal Recurrence. If you want to live over and over again those interludes of great happiness, then you also have to live over and over again the bad-back bits and the shit-cake bits. It’s not like a game of football where you can enjoy the highlights condensed down into five minutes.

One sentence that I think is key to the understanding of your writing is from the preface of Yoga For People Who Can’t Be Bothered To Do It: ‘Everything in this book really happened, but some of the things that happened only happened in my head; by the same token, all the things that didn’t happen didn’t happen there too.’ Could you elaborate on this?

One of the reasons I have such a love for D.H. Lawrence, particularly as a travel writer, is this knife-edge that he’s walking on all the time. He had this incredible responsiveness to place.

…..He wrote that amazing essay, A Letter from Germany, in 1924, when he was in the Black Forest, he says something like, ‘I can feel something here, some turning back of civilisation,’ and you think, God, he’s just feeling the wind, but he’s sort of apprehending the rise of Nazism! And this happens repeatedly. For example, his intuiting a sense of the Aboriginal dreamtime when he’s only been in Australia a few days. So all of that is incredible. On the other hand, there are moments when it’s such a complete projection of his inner life onto a place that it has no objective value at all.

…..I find this tension, this knife-edge, incredibly exciting, because it’s so volatile.

❦

Thanks to Luke Ingram at Wylie UK, and to Aisling Holling at Canongate for her help and attention.

Books by Geoff Dyer

— (2025). Homework: A Memoir

— (2022). The Last Days of Roger Federer: And Other Endings

— (2021). See/Saw: Looking at Photographs

— (2018). The Street Philosophy of Garry Winogrand

— (2018). Broadsword Calling Danny Boy

— (2016). White Sands: Experiences from the Outside World

— (2014). Another Great Day At Sea: Life Aboard the USS George H.W. Bush

— (2012). Zona: A Book About a Film About a Journey to a Room

— (2011). Otherwise Known as the Human Condition: Essays and reviews 1989–2010

— (2010). Working the Room: Essays and reviews 1999–2010

— (2009). Jeff in Venice, Death in Varanasi (novel)

— (2005). The Ongoing Moment

— (2003). Yoga For People Who Can’t Be Bothered To Do It

— (1999). Anglo-English Attitudes: Essays, reviews, misadventures 1984–99

— (1998). Paris Trance (novel)

— (1997). Out of Sheer Rage: In the Shadow of D.H. Lawrence

— (1994). The Missing of the Somme

— (1993). The Search (novel)

— (1991). But Beautiful: A Book About Jazz

— (1989). The Colour of Memory (novel)

— (1986). Ways of Telling: The Work of John Berger