SOLO TRAVELLER

xx

xx

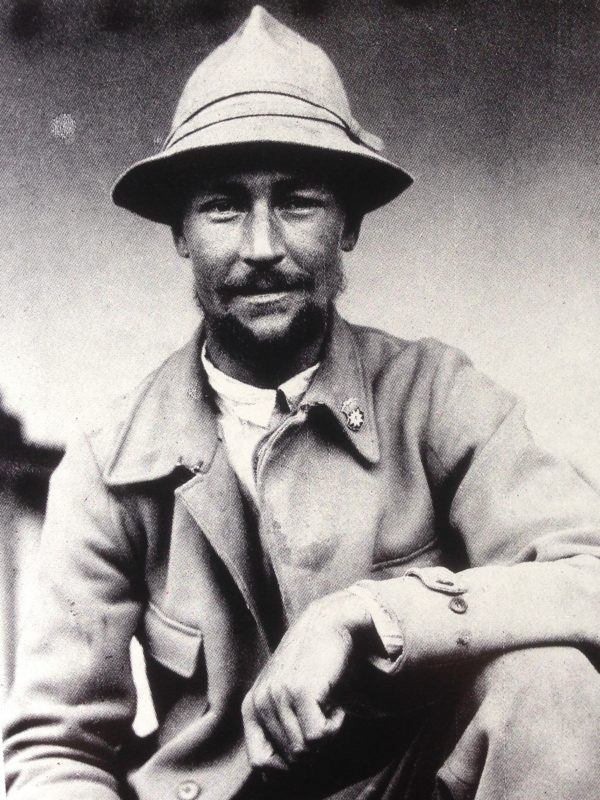

He was an alpinist, agricultural expert, aid worker, cartographer, and archaeologist: In the spring of 2019, a biography of Peter Aufschnaiter, who would have been celebrating his 120th birthday this year, has been published. In it, author Nicholas Mailänder follows the tracks of this man who had always walked in the shadow of Heinrich Harrer (Seven Years in Tibet) – and who also had no desire to be in the spotlight.

(by Simon Schreyer. Appeared in Unterwegs Magazin, Summer 2019)

xx

Peter Aufschnaiter was a quiet man. He was self-sufficient. He felt uncomfortable standing in the limelight or being celebrated. Long before the concept was even generally known, he was a pioneering aid worker in Tibet, Nepal, and India.

Aufschnaiter felt most at home in nature. Growing up in Aurach, south of Kitzbühel, he explored the ‘Südberge’, while as a young man he climbed the difficult routes in the Wilder Kaiser range. As an elderly man, he trekked alone for hundreds of kilometers through Nepal and Tibet.

xx

xx

© Simon Schreyer

In his youth, he was influenced by the idea of a unified German people and joined the NSDAP after Hitler’s rise to power. And by the same token, he found everything to do with pomposity, war, and clamor abhorrent. When in the Gaudeamus Hütte (a refuge in the Kaiser range) a Bavarian and a Tyrolean were quarreling and filmmaker Jan Boon wanted to intervene, Aufschnaiter took him by the shoulder and whispered: “Leave it, it isn’t worth it!”

xx

© planetmountain

xx

After his military service on the Dolomites front line in World War I, and studying agricultural sciences, he found work with mountaineer Paul Bauer as a Managing Director of the ‘Deutsche Himalaja Stiftung’ in Munich. In 1929 and 1931, Peter Aufschnaiter took part in expeditions to Kangchenjunga, the world’s third-highest mountain, where he reached a height of 7700 m on the mountain’s North East Pillar. He also investigated the isolated North of Sikkim and, for the first time, viewed the vast expanse of the Tibetan landscape.

xx

xx

In 1939, he was the leader of an expedition to Nanga Parbat and discovered a variant on the Diamir Face, the so-called ‘Aufschnaiter Rib‘. In the meantime, World War II had broken out and the expedition team was captured by the British on their return journey. After four and a half years of imprisonment in India and numerous attempted escapes, Aufschnaiter, together with Heinrich Harrer and five others, escaped.

It was Harrer and Aufschnaiter – in terms of character probably complete opposites – who, after almost two years and an adventure-packed getaway through Tibet’s Tsangpo Valley and the Changthang high planes, reached the forbidden city of Lhasa. This was only possible because the linguistically gifted Aufschnaiter knew Tibetan. After unimaginable hardships, the two men first laid eyes on the Potala Palace in January 1946 – clothed in rags and furs and at the end of their tether.

This story of two fugitives, who tackled the highest mountains on the planet and became advisors to the king in a mysterious realm, has become part of global culture thanks to Harrer’s bestseller Seven Years in Tibet (and its Hollywood adaptation in 1997, with Brad Pitt and David Thewlis).

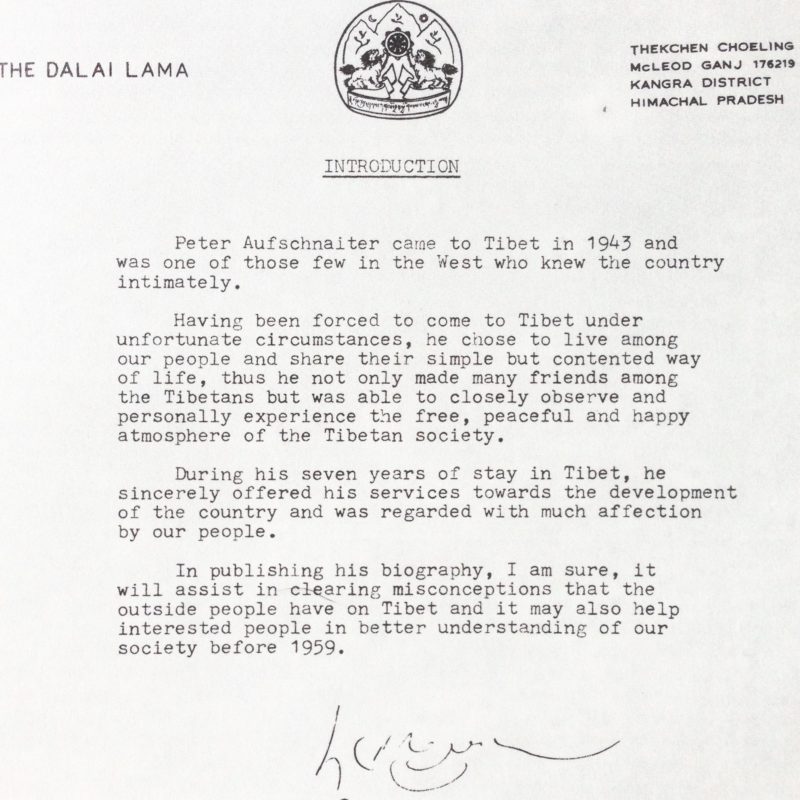

Between 1947 and 1950 Aufschnaiter earned a living as a high-ranking official at the court of the XIV. Dalai Lama.

Together with Harrer, he drew the first precise city map of Lhasa, and his hydro-power station at Kyiu Chu (‘Happy River’) is still in operation today. He worked as a sewage system engineer and, as a seed expert, prevented a famine by importing and planting highly resistant crops.

He corresponded with Italian archaeologist Giuseppe Tucci and befriended the handful of other foreigners in Lhasa, among them Scottish diplomat and Tibetologist Hugh Richardson.

The sacred art of Tibetan Buddhism was a topic of great interest to the Tyrolean and he studied ancient texts and paintings. In the reclusive poet and mystic Milarepa (1052 – 1135), he found a kindred spirit and made countless pilgrimages and expeditions to the gompas and caves where the Tibetan saint had meditated and composed his ‘Thousand Songs’.

The passionately independent Aufschnaiter was a bit of a hermit himself and never married but he was very fond of Tessla, a daughter of Lhasa-merchant Tsarong, who later married into the Bhutanese royal family.

When not busy with his many projects, he lived in a small country estate. Aufschnaiter: “If Tibet had not been occupied by China in 1950, I would have stayed there for the rest of my life. In all the years that I spent there, I thanked the heavens above each and every day that I had been granted this fortune.”

Of the Tibetan people, he said: “At times I lived more simply than many of the simple people. I recognized their joys and their worries – little worries that were nonetheless big worries for them. I worked with them in the fields and on the construction sites, and I knew those who exploited the workers and farmers and became rich that way. I don’t blame them. After all, the innocence of their hearts was also written on their faces.”

xx

xx

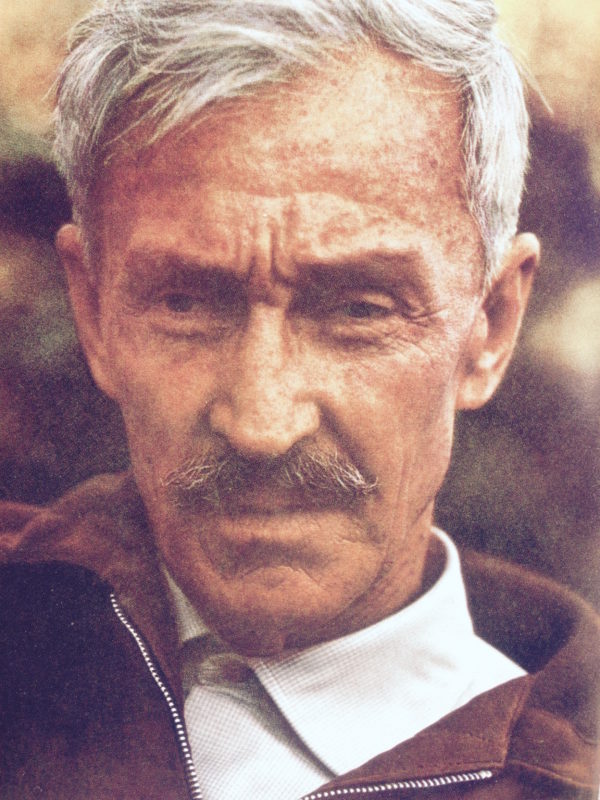

After his flight from Tibet in 1952, he was employed for many years at the Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN in Kathmandu and New Delhi. Yet he found offices grim. He spent every holiday in the mountains, for the most part with British and Canadian alpinists. In his late 50s, he first-ascended Ronti (6063 m) in the Garhwal, north of Nanda Devi, and climbed Chusumdo Ri (6609 m) in the Langtang Himal – with only one partner and in minimalist alpine style.

He stored the geography of the Himalayas in his head like no other person – and thus he documented the northern border of Nepal, explored the north side of Everest, and was the first to survey prominent summits and 8000-meter-peaks such as Shisha Pangma.

In the early 1960s, Aufschnaiter, by now a citizen of Nepal and a family friend of the Rana princes, traveled to the remote region of Dolpo and to the forbidden Kingdom of Mustang, where he discovered precious Buddhist frescoes.

While many of his conservative European friends were disgusted by the growing waves of longhaired Western youths invading India and Nepal after 1966, Aufschnaiter understood their spiritual rebellion against industrialization and conformity.

In his diary, he noted: “The hippies take their worldview from science and from a sort of pagan naturalism. If I understand their view of humanity’s position within the time-space universe correctly, they are, in a way, spiritual descendants of Milarepa. His observations are based on the illusory and transitory nature of creation.

Milarepa pointed out the difference between logical conclusions and meditative wisdom. His view, like that of Heraclitus or the medieval mystics, is more obscure and arcane. I am of the opinion that this mysticism is closer to the truth in making sense of the material world, and, I believe, more perennial.”

In the autumn of 1964, Aufschnaiter took a solo trip around the world (Kathmandu – Delhi – Beirut – Jerusalem – Rome – Munich – Hamburg – London – New York – Los Angeles – Las Vegas – Honolulu – Tokyo – Hong Kong – Kolkata – Kathmandu). Every second or third year, he visited friends and family in Kitzbühel, St. Johann, and Munich.

At the end of his eventful life, he was asked when he had been at his most happy. His reply: “When I was hiking across the rolling planes of Tibet. Alone.”

The Dalai Lama’s younger sister, Jetsün Pemà, wrote the following words after the death of Peter Aufschnaiter in 1973: “His love was directed at the Himalayas and the people of this region. He revered them in a quiet way and it was this that was the loveliest thing about him.”

xx

xx

✺

xx

© Heinrich Harrer

xx

Now an exciting and well-researched biography by Nicholas Mailänder and Otto Kompatscher recounts the life of this modest and graceful globetrotter, published by Tyrolia Verlag: Er ging voraus nach Lhasa.

Plans for a translation into English are underway.

xx

xx

xx

xx

xx