SEARCH AND DISCOVER

xx

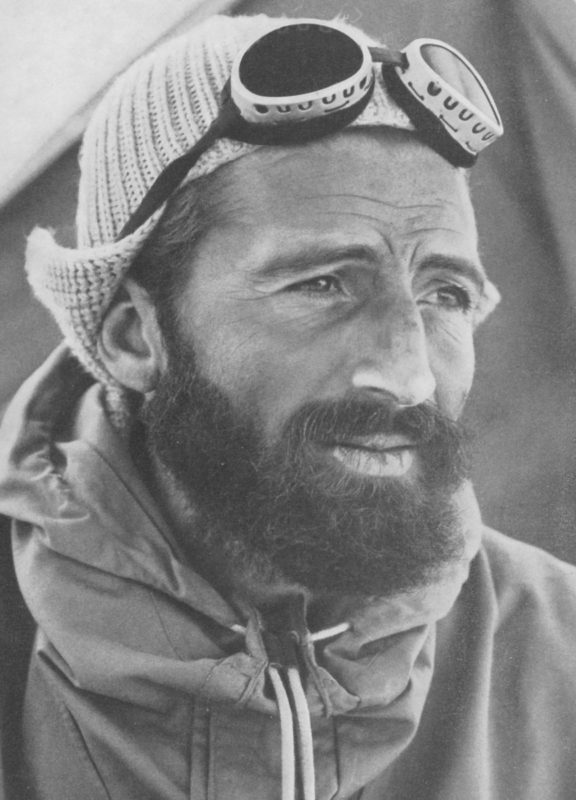

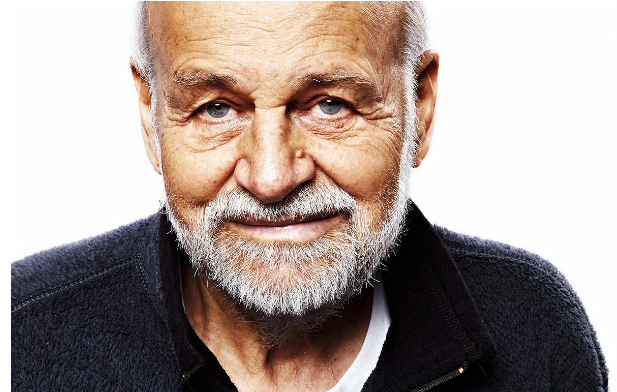

Kurt Diemberger (*1932) is a living legend among mountaineers. He has released award-winning documentaries, and so far, published seven impressive and often quietly philosophical and lyrical books. During his travels, he has also taken highly acclaimed photos in the least accessible regions of the world. Diemberger is the only person who has not only one but two first ascents of eight-thousanders (summits over 26,247 ft) under his belt: Broad Peak in 1957 and Dhaulagiri in 1960.

xx

xx

In the 1950s, young Kurt and his climbing partner Wolfgang Stefan mastered the three major Alpine north faces: the Matterhorn, Eiger, and Grandes Jorasses via the Walker Spur. Together with Franz Lindner, he traversed the entire Peuterey ridge of Mont Blanc. After Diemberger climbed the cornice “Schaumrolle” on the Königspitze in South Tyrol, Hermann Buhl—at the time the world’s best all-round mountaineer and the celebrated first climber on top of Nanga Parbat—took notice of him.

Diemberger—only 25 at the time—would turn out to be Buhl’s last rope partner, first on Broad Peak and ultimately on Chogolisa in 1957. Tragedy struck again when Diemberger lost his partner Julie Tullis during a five-day storm in K2’s death zone in the “Black Summer” of 1986. Until then, they had been known as the “world’s highest camera team”.

This gruff but warm-hearted Austrian has climbed the fiercest Alpine faces and Himalayan ice giants, but he did not limit his focus to the vertical world; he conducted expeditions to Greenland and South America, and many times, he explored the uninhabited and fascinating Shaksgam Valley of Xinjiang.

Kurt Diemberger could always rely on his instinct when it came to choosing the right partner for a mountain and with his incredible sixth sense, he has escaped numerous extreme and apparently hopeless situations.

Describing himself as a freedom-loving individualist, he never wanted to bow down to sponsors or organisations; he wants to be understood as a vehement opponent of sensationalistic and competitive mountaineering and the commercialisation of alpine sports.

In this interview, Kurt Diemberger took heart to talk about the sense and nonsense of speed climbing, the last trace of Hermann Buhl, the fascination of Alpine geometry, the vociferous take-over of mountaineering by advertisers, and the quiet atmosphere of Shaksgam Valley.

(Simon Schreyer, 2013)

xx

xx

✺

xx

xx

You started out as an alpinist because you were looking for crystals, and you could say that the Himalayas are enormous crystals. In your first book Summits and Secrets (Allen & Unwin, 1970), you dedicate an entire chapter to “Alpine Geometry.” How important was the “beauty of a mountain” to you when you considered climbing it?

It’s possible that searching for crystals in my teens played an important role. Since you mentioned it, maybe the term Alpine geometry makes that a little clearer: I have always been impressed by mountains that just had that special something in their lines and their aura in general. And in that respect, K2 is the biggest crystal in the world. Another example is the Direttissima through the Königswand (Gran Zebrú).

But there are also examples of this in my photojournalistic works that don’t necessarily have anything to do with climbing. There is a certain view from the north face of Mont Blanc de Cheilon. Looking down from this wall, I experienced a fascinating play of light and shadow on the glacier beneath me that could just as easily have come out of Saint-Exupéry’s The Little Prince. So, imagination also plays a role in drawing you to it, the athletic challenge certainly isn’t everything.

Did this apply to Hermann Buhl, whom you have often described as your mountaineering father?

I’m not quite sure. He also had the drive to accomplish something new in the world—and that includes the world of mountaineering. He was the creator of the Alpine Style, which we put into action during the Austrian Karakoram Expedition in 1957. When Marcus Schmuck, Fritz Wintersteller, Hermann Buhl, and I first-ascended Broad Peak (8051m), we did so without high-altitude porters and oxygen. And when Buhl and I climbed Chogolisa (7654m), we already used a more lightweight West Alpine Style along with one single high camp. This has become the general Alpine Style by now. In 1975, Reinhold Messner and Peter Habeler used this style for the first time on an eight-thousander, Gasherbrum I (8080m; note: also known as Hidden Peak). Messner referred to us in one of his books; other than that, it’s a little-known fact.

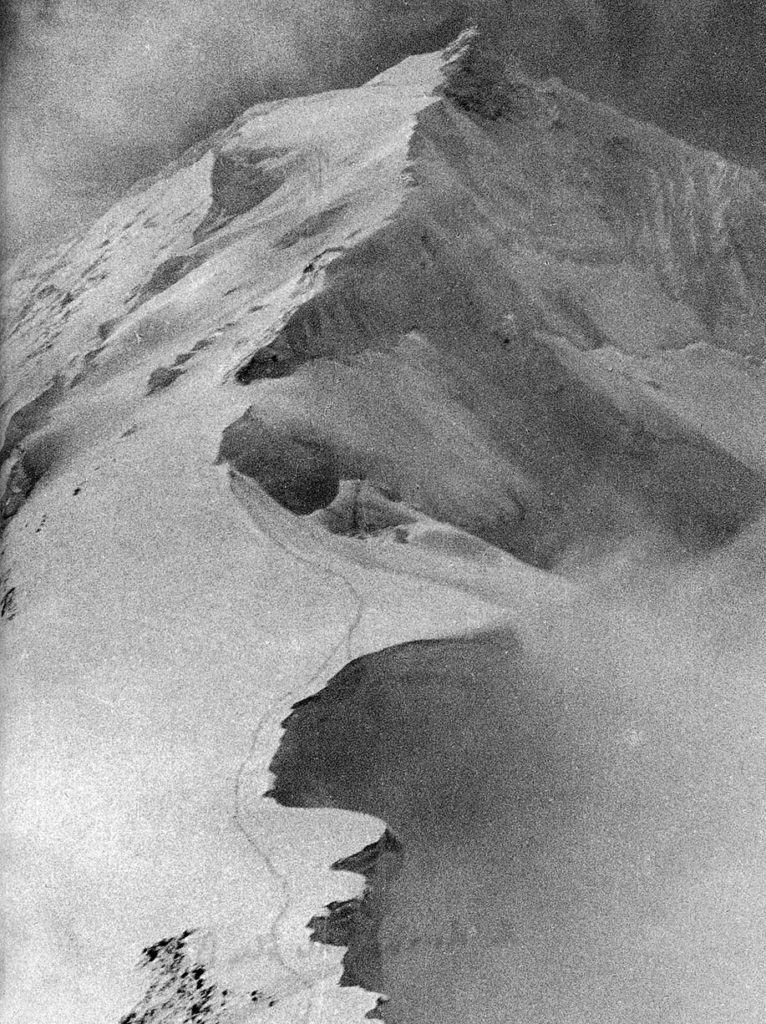

Chogolisa in the Karakoram Himalaya has been compared to a bride because of her soft lines and fluted ice walls. It’s also considered to be the most picturesque roof-shaped mountain in the world. Why have you never tried to climb Chogolisa again after Hermann Buhl died there in 1957?

I never even considered this mountain again because Chogolisa without Hermann — what would be the use of that? I lost him there (Note: While Buhl and Diemberger were retreating due to a snowstorm, Buhl broke off with a massive cornice, triggering a huge powder avalanche, and crashed down 900 m into the glaciated and cauldron-shaped northern flank, never to be seen again.). I’ve never even thought about it and I think no one else has either. But if you want to talk about our different motivations at the time… During the expedition to Chogolisa, Hermann was obsessed with making this idea come true, namely, ascending such a gigantic mountain in only three days and not three weeks, as we did on Broad Peak. He wanted to prove that it was possible. It was this drive to attain, which I call the Seventh Sense. But it can never quite silence those small voices in the back of your mind that tell you “Turn around! It’s too risky!”

xx

© K. Diemberger

xx

Do you think those are doubts that you have when you’re faced with apparent danger or are they warnings, issued by this sixth sense?

The obvious objective danger of Chogolisa lay in the slabs that the wind had pressed against the side of the crest. Because of that, we were forced to walk close to the cornice-laden escarpment of the Northeast Face in some places and we had to stay relatively far away from each other. It had been a lot easier when we were crossing the so-called Ice Dome (7150m) because the snow was a lot harder there.

© Hans Ertl, ZADA

In the place where the big cornice broke during our descent (Note: Diemberger went ahead), it looks like our trail was dangerously close to the edge of the cornice, but in reality, a large chunk of snow surface broke away in between. And on top of that, Hermann had already stepped out of my trail. I was already out on the edge of the huge cornice myself. When suddenly the snowfield around me trembled, I instinctively jumped a few meters to the right. Out of the corner of my eye, I still saw flakes of the cornice breaking away to my left.

Is it possible that Buhl thought the dark edge of the cornice was your trail because of the snowstorm?

No, no, that isn’t possible. My steps were too distinct for that. And he could probably still see me because we were only 10 meters apart. There are several reasons why he might have stepped out of my tracks: Maybe there was a gush of wind and snowflakes that suddenly coated his goggles; or maybe, when he saw the curve in my tracks, he thought, “Gosh, why does Kurt go so far to the right? All right, I’ll walk there roughly but not as far below,” and so he stepped out too far onto the overhanging cornice. There have been a lot of assumptions about this accident, but in the end, we just don’t know. The fact is that we weren’t roped which is always a mistake in a situation like that. But, had we used the rope, I probably wouldn’t be here anymore because Hermann would have pulled me after him into the abyss. That means I owe my life to a mistake.

xx

© K. Diemberger

xx

Do you see yourself as a pioneer of what’s considered to be ‘extreme sports’?

I don’t think so. I’m not a pioneer of extreme sports and I don’t have anything to do with high speed and other records; it’s actually the opposite: I’m a known proponent of slowness, as long as we’re not talking about moving across couloirs or avoiding an approaching storm. If you walk slowly, you walk well. If you walk well, you walk far. I’m living proof of that. My understanding of extreme sports is that it’s not about finding the path, the solution to a mountaineering problem; it’s about adding a new, more risky line to one that already exists. I often feel like it’s all about immortalizing your name. I’m not a friend of extreme sports, especially not when it’s all about speed records.

xx

xx

xx

xx

“If you walk slowly, you walk well. If you walk well, you walk far.”

xx

xx

xx

xx

Are there exceptions in your mind?

Of course, some excellent mountaineers can climb safely at high speed. There’s Ueli Steck (1976 – 2017), for example. He climbed the Eiger’s North Face in 2 hours and 47 minutes. It’s certainly remarkable but I always ask myself, first of all, why, and secondly, what can you even see along the way? He probably only sees what he needs to be fast. So, it’s simply an athletic performance.

xx

xx

xx

It seems that your motivation as an alpinist is more comprehensive.

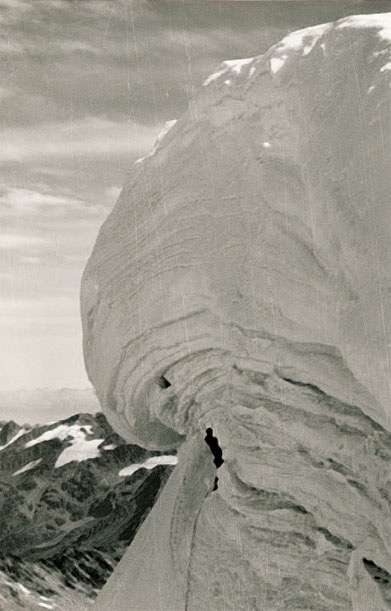

To me—remember, I was initially looking for crystals —mountaineering is mainly about discovery. It always has been. I would ask myself: „What’s behind that next ridge or ledge? What is the view up there like?“ When I think back to the Schaumrolle at the Königspitze (also known by its Italian name Gran Zebrù), there are several reasons why I wanted to climb it back in 1956. The main motivation was: What does it look like inside this formation that I had pictured as a blue ice dome from down below?

Only the second reason was athletic by nature: Could there be a way for me to get across or through this massive dome? But the Schaumrolle didn’t only give me those two aspects—the explorative and the athletic one—it was also my first contact with competitive mountaineering. (Note: Diemberger met the rope party of Knapp/Unterweger in the Schaumrolle and later on, they had a falling out regarding who came first. The object of contention—the Schaumrolle—which was the most massive summit cornice of the Alps at the time, broke off in the summer of 2001.)

You are known for your opposition towards commercialized and medal-rewarded alpinism. Would you like to comment on that?

I’m against the excessive sponsoring we have today, and I’d like to see more moderation instead of the unregulated invasion of advertisement into alpinism. Mountaineers today are plastered in all sorts of branding from head to toe. If it’s for an expedition—all right, it’s OK to have a sponsor to support them. We’ve had sponsored expeditions since the beginning. In the 1950s, for example, Sport Scheck in Munich (Note: a sporting goods store) sponsored our equipment for the Broad Peak expedition. When Julie Tullis and I went up Mount Everest in 1985, the glass company Pilkington paid for practically everything, and in return, they took the liberty to make adverts with it. I think you could still call this “sponsoring by-fair-means”.

In addition to the mountains of the Karakorum, you’re also fascinated by the remote desert of Shaksgam Valley to their north. What does it look like?

Shaksgam Valley is the big unknown on the other side of K2 and the Gasherbrums – the Chinese side. It is a 200-kilometer-long river valley. Most of the time, it’s dried up and only a little bit of water trickles through in between the stones. But when the glaciers melt in July and August, the whole valley is flooded. There are still so many unknown mountains and nameless crests there. Over there, the golden age of discovery is not over yet; there are mysteries to discover and plenty of paths that nobody has walked before, even to the eight-thousanders. For example, no one has ever tried to climb Hidden Peak (Gasherbrum I) from that side. A Japanese party tried to get through, but they had to turn around when they hit a sawtooth ridge at 6400 meters. If someone wants to climb up there, they should probably do it soon because these phenomena may soon disappear due to climate change. The whole ridge is changing, as we speak.

xx

xx

xx

What is it that fascinates you about this valley?

The fact that it is one of the least accessible areas in the world. Nobody lives in this mountain desert and it has a wonderful ambiance. To reach Shaksgam, you have to cross the Aghil Pass, which is almost as high as Mont Blanc. Before reaching the pass, one passes through one last Kirghiz village. I definitely want to go there again. The Americans have been calling me the “Shaksgam janitor” because I know the valley like I know the back of my hand. There’s still a barrel of materials hidden under a moraine from my seventh expedition to Shaksgam back in 1999, and there’s a piece of paper attached that says “Still needed!”

xx

✺