HIGH AND FREE

xx

xx

xx

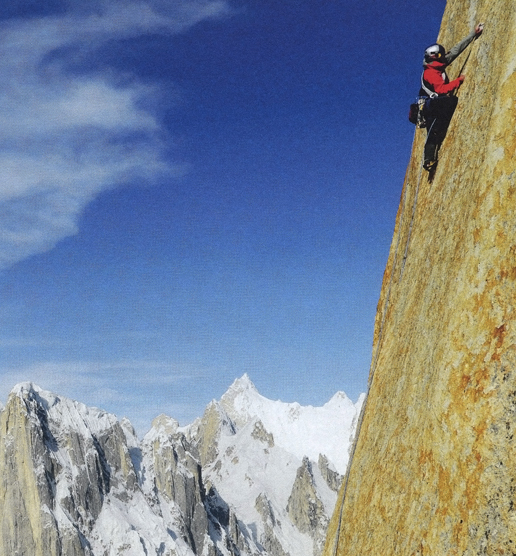

David Lama (1990 – 2019) was one of the world’s cutting-edge alpinists. He also was one of the most gifted climbers of all time, discovered already as a child.

After quitting the international competition circuit, having won everything there is to win, this Austrian with Nepalese roots caused a sensation in January of 2012: He free-climbed Patagonia’s fabled granite needle Cerro Torre, via the infamous Compressor Route.

As the stars aligned for David, he and his partner Peter Ortner scaled Trango Tower (6251 meters) via the route Eternal Flame and the entrancing Chogolisa (7665 meters) in Pakistan’s Karakoram Range.

In the autumn of 2012, I caught up with him to interview him about this latest expedition beyond the clouds.

In the spring of 2019, David Lama lost his life, aged 28, in an alpine accident in Canada. In subsequence to the interview, you can read an account of the circumstances of his death, as well as a few thoughts and personal memories.

(Simon Schreyer, 2012 / updated 2020)

✺

© Corey Rich / Red Bull Content Pool

xx

David, last year you were on a climbing trip in the Indian Himalayas with fellow climbers Stef Siegrist, Rob Frost, and Denis Burdet. You spent months in windswept Patagonia, and now you just came back from the Karakoram. You seem to be looking for your projects in the wildest and most remote corners of the planet, right?

The mountains I am interested in for my projects just happen to stand in the wildest places of the planet, that’s all. But naturally, this adds to their fascination for me.

When we climbed Cerro Kishtwar (6155 m) in India last year, we had to trek for three days through a deserted valley. Because of the border disputes between Pakistan and India, the area was closed for 20 years and has only recently been reopened. This trip to the Baltoro Glacier also took us into uninhabited territory. The last village we entered on the expedition through Pakistan was Askole. That’s about 3000 meters high and from there it was a three-day trek to the glacier.

Your first goal in the Karakoram Mountains was the Trango Group. Were you by yourselves on the steep walls of these famous monoliths?

The Trango Group is not very accessible, so there were no trekking groups around when we got there. However, there were a lot of other mountaineering teams from all over the world. A little too many for my taste (chuckles).

Who were your climbing partners on this expedition?

I traveled with Peter Ortner for the entire duration of the trip – we had scaled Cerro Torre free in Patagonia together earlier this year.

I also have to acknowledge the contribution of the three-man film crew who followed us up to the Trango Group: photographer Corey Rich, cameramen Andrew Peacock and Remo Masina. Corey accompanied us to the summit of Trango Tower.

xx

xx

Clip: David Lama and Peter Ortner on Trango Tower

xx

xx

How did you deal with the challenges of the extreme altitude?

Generally speaking: really well. On our ascent of the Trango Monk (5850 m), we were a few hundred meters below the summit but had to turn back because we were not yet fully acclimatized. It was especially tough for Peter because this was his first expedition to a really high mountain.

A few days after that, we started to scale Great Trango (6286 m), and again we had to turn around near the summit. This time it was because of avalanches rather than altitude sickness. Lots of snow and ice from the last harsh winter in the wall’s cracks and a sudden spell of warm weather could have turned into a substantial source of danger for us.

xx

xx

xx

xx

xx

xx

And then your attention turned to the Eternal Flame route (IX+ / 5.13a / 7c+) to scale Trango Tower, also known as Nameless Tower (6251 m)?

Exactly. The route was established in 1989 by Kurt Albert, Wolfgang Güllich, and friends (Milan Sykora, Christoph Stiegler; ed.). It leads up pretty straight on this enormous, smooth south face. The Huber brothers freed it only three years ago.

Did you manage to free-climb the route?

It would have been awesome if we could have had an attempt at free climbing the route — for sure. Unfortunately, there was just too much rime and ice in most of the cracks for that, and more bad weather was predicted by Charly Gabl. So we decided already at Base Camp to put all our efforts into a light and quick technical ascent.

It took us one day to reach the ‘sun terrace’ after 400 meters in grade 8. There we set up camp and continued the next day, June 30th. We needed 10 more hours to complete the final 600 meters to the summit. Despite all those other teams in the wall, climbing Eternal Flame is one of the best things I’ve ever done.

After the Trango Group, your next mission was the trapezoidal snow peak Chogolisa (7665 m), a mountain that is as beautiful as it is steeped in history. Did you spend time thinking about the legendary Hermann Buhl who lost his life on the East Ridge in 1957?

Hermann Buhl is a name I know and respect but I’m always trying to do things in my way rather than follow in anybody else’s footsteps.

We didn’t hike up Chogolisa to brag that we went beyond the 7000-meter mark, we wanted to experience how our bodies would feel and function at that altitude. Peter and I are not at all about records or about making it to the top of Everest by any given means.

Still, we need altitude experience for our future climbing projects.

xx

xx

Clip: David and Peter on Chogolisa

xx

xx

xx

xx

xx

What can you tell us about your expedition to the summit of Chogolisa?

Well, first of all, Chogolisa was a damn tough hike! Additionally, you have to deal with horrible weather conditions in this corner of the Baltoro: Out of 18 days in our base camp on the Vigne Glacier it snowed or rained for 14 days.

A first attempt brought Peter and me to 6800 m. However, unexpected clouds rolled in from the South and we had to retreat to base camp in a heavy fog, which was quite precarious in itself. A few days later, we tried to make use of the last predicted weather window and ascended to our last high point. There we slept underneath a small sérac and started our summit push at midnight, under a starlit sky.

It took us another nine hours to break trail through this enormous flank.

This means, on average you only made something like 100 vertical meters in an hour.

That sounds about right, probably even less. In some sections, we were moving through waist-deep snow, so this slowed things down a lot. Then, when you pass 7000 meters, every step becomes a massive effort. You take 20 steps and just lean into your ski poles, gasping for air. After two minutes, you take another 20 steps.

Some locals had given us a tip that we should hunt an ibex because eating their flesh helps with altitude sickness. I’m not sure about this theory and we didn’t get the chance to test it because we were unable to catch one with our bare hands!

Chogolisa may not be the toughest climb technically but we were very proud when we finally stood on top. We were only the seventh party to reach the summit and the first one since 1986 (editor’s note, 2022: According to the chronicle in Andy Fenshawe’s book Coming Through – Expeditions to Chogolisa and Menlungtse, since 1987. David and Peter were the 24th and 25th climbers, and indeed the seventh party, to reach Chogolisa’s true summit. It has not had any more visitors since their ascent in 2012).

xx

xx

©Peter Ortner

xx

xx

Will you be returning to the Karakoram?

Peter and I already have one other peak targeted that we would like to go back to and scale.

The Himalayas are just one huge playground for climbers. I love the freedom of choosing routes up the walls because there are so many options you can take. I don’t pay too much attention to the historical significance of a summit.

A mountain is just a pile of rocks and stones and pebbles; it isn’t gorgeous or wild or dangerous or ‘mystical’ by itself. It is so because we humans regard it with such significance. It is all connected with us.

xx

xx

xx

xx

xx

xx

xx

xx

xx

This interview appeared in a different form at redbull.com in 2012.

xx

xx

Video (Update 2016): David Lama – Life is a Playground

xx

xx

xx

Dieses Interview auf Deutsch lesen

x

xx

✺

xx

xx

Update, 2020. In the early afternoon of Tuesday, April 16th, 2019, David Lama, Hansjörg Auer, and Jess Roskelley perished in an avalanche on the east face of Howse Peak, one of the gnarliest rock-and-ice walls in the Canadian Rockies.

Their positions on the mountain were recorded by the team’s various phones and camera devices and later Google-Earth-tracked and analyzed by John Roskelley.

John, Jess’ father, is one of the most accomplished mountaineers of his generation and an expert analyst of alpine accidents. His public presentation of the facts, photos, and data took place at the Piolets d’Or 2019 ceremonies in Poland. The following short account is based on his extensive research and report:

Hansjörg, David, and Jess started their ascent shortly before 6 A.M., on a cold and cloudless morning. Occasional veils of spindrift enshrouded Howse Peak’s walls and chimneys.

Leaving the notorious M-16 route (first ascended by Steve House, Scott Backes, and Barry Blanchard in 1999) about halfway up, the three climbers traversed left, up a frozen waterfall that is the topmost part of a still unclimbed route named King Line. Then they broke trail up a steep gully and over a rib of deep snow.

Crossing the rib, they pioneered towards a distinct triangular rock feature that hovers darkly over a vast, funnel-shaped basin, or ‘cirque’. Soloing a 35° to 45° couloir of about 160 m (525 ft) in length, and 30 m (98 ft) in width, they reached the crest of the spire that would lead them to the summit plateau.

Within seven hours, they had put up a new line on the very left side of Howse Peak’s east face.

Following their extremely fast ascent, Jess, Hansjörg, and David topped out in high spirits around noon, as a selfie with the timestamp 12:44 P.M. from Jess’ phone proves, and then started descending the same way down the southeast pillar.

By 1:27 P.M., the climbers were rappelling back into the couloir between the main southeast ridge and the arête leading to the dark triangle. They unroped and began plunge-stepping down the boot-deep slope to reach the large snow rib – their exit from this obviously unsafe zone.

Shreds of clouds scudded swiftly between the mountain and the midday sun.

At the same time, Quentin L. Roberts, a climber from Canmore, was observing Howse Peak from Icefields Parkway, allegedly unaware of someone being on its face. At 1:58 P.M., he and his partner witnessed and later reported a cornice toppling over from a ledge below the summit and tumbling down into that same couloir.

He even took a snapshot of the resulting avalanche sweeping the mountain’s lower shelves and raising powder plumes from its shady base high into the light. Like many peaks in the Rockies, Howse is a stack of horizontal, slanted bands with negative curbs. Once a small slide releases, it shakes the snow-laden ledge below and so on and so on, in a domino of doom.

“It looked like the whole mountain was falling apart,” Roberts commented.

xx

xx

xx

As stated by avalanche.org, cornices are elegant, cantilevered snow structures formed by the wind on ridge lines. They are fatal attractions in the mountains, their beauty matched only by their danger.

Think of a rolling ocean wave sculpted of dense, solidified snow and ice. Slowly, the wave grows and grows over many weeks, months, or even several winters. Until, at some unpredictable point, it gets too heavy and falls off the ridge.

Canadian alpinist Barry Blanchard once remarked that the sound of a large cornice break is not unlike the cracking of a felled fir. The muffled thump of its landing on the slope can make the entire mountain flank tremble, and usually triggers an avalanche, or the cornice breaks into hundreds of pieces and forms its own avalanche—or both.

Channeled through a steep flute or a narrow couloir, a cornice avalanche remains slender but accelerates to 45 km/h (30 mph) within the first 3 seconds and up to around 145 km/h (90 mph) after 7 seconds. Extreme skiers call such an avalanche a snow fist.

Most probably killed instantly by the impact, David, Hansjörg, and Jess were swept down the slope towards a ramp-like ledge and projected over a tall icefall route called Life By the Drop which drains the cirque as a pipe drains a sink. Carried by the avalanche for 800 vertical meters (2625 ft), they came to rest on top of an old avalanche cone.

Many more slides came down the face during the stormy night which soon descended upon the scene of desolation. It took the SAR team five days to recover the bodies, due to fog, snowfall, and further avalanche danger.

The state of the equipment and ropes found with the climbers suggests that they heard the release of snow and ice behind them, stopped in their tracks, and turned around. Jess tried to self-arrest with his ice tools, just as his partners instinctively must have done too.

However, only Jess’ right-hand ice tool was connected to the two coiled (and loop-locked) ropes he had been carrying over his shoulders when the avalanche hit them. Within a second, the blast wave ripped Jess from his stance, the carabiner right out of the ice-axe handle, and the ice-axe out of its hold. The Camp Nano carabiner itself, resisting 21 kN (more than two tons of inertia force), was mangled badly out of shape.

The bodies were found close together and covered by a shallow layer of snow (max. 90 cm / 3 ft) from a subsequent slide. During a first recognition flight on the day after the accident one body had been spotted only partially covered – a further indication of a cornice break, or a comparably small slab or snow-pillow fail, having caused the avalanche.

In his captivating long-read ‘The Dying of the Light’ for Outside Magazine, writer Nick Heil recounts that Parks Canada received more than 800 inquiries about the tragedy. All three men were on the global The North Face Athlete Team, and among the world’s premier alpinists.

They were, as Conrad Anker has called them on Instagram, a ‘solid team’.

xx

© H. Auer

xx

I didn’t know legendary John Roskelley’s son Jess, but I had heard of his achievements in Alaska and the Andes. The more I read up on him, the more impressed I am. I also like that he had a superb sense of situational comedy and that he was a proud husband and a welder. According to his family, Jess was absolutely psyched to climb with the two Austrian ‘flying Gods’.

Hansjörg was an exceptional person, who had to endure much hardship in his childhood, being ridiculed by classmates for his big teeth and long bones. He sought solace in the wilderness of his home mountains and learned to harness self-sufficiency and solitude to become one of the most astonishing free soloists of our days.

His free solo of ‘Weg durch den Fisch’ (IX-/7b+/5.12c) through Marmolada’s South Face, in 2007, is one of the all-time highlights of climbing history. ‘Hänsen’ realized inspired projects in Patagonia and Pakistan – especially his solo ascent of Lupghar Sar West (7200 m) was a showpiece in pure Alpine style, honored with a Piolet d’Or, posthumously.

He was an honorary member of the Paul Preuss Society and Reinhold Messner’s “darling” among the up-and-coming mountaineers. I heard about plans to repeat the Kurtyka/Schauer line on Gasherbrum IV’s shining western wall, or even a new route to its formidable summit.

I had arranged an interview with Hansjörg for a few outdoor magazines six weeks prior. At the end of March, he postponed our meeting to the week after Easter because of ‘a climbing trip to Canada’, and wrote that he was looking forward to the conversation after he would be back.

xx

xx

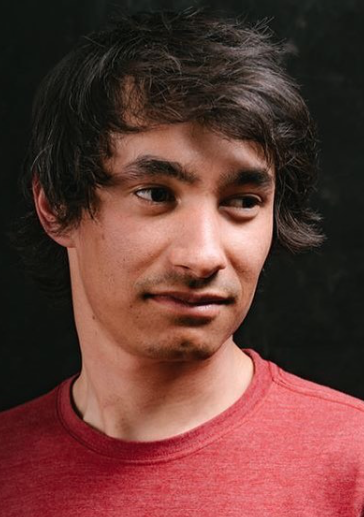

David Tsering Lama was one of the most together people I have encountered. He was just all-around likable as a human being: shy, yet shining with self-confidence and a knife-sharp presence. At close range, his charisma was almost unbearable. He could also swear in Tyrolean and be a cheeky rascal like nobody’s business.

David’s grandfather had been a Buddhist monk (hence the surname) from the dusty plains of Tingri, in the Tibetan prefecture of Shigatse, 50 miles to the northeast of Cho Oyu, as the crow flies. This lama resigned from his religious duties and settled down in the Solu Khumbu to marry a Sherpani and have a family after the Chinese occupation of his Tibetan homeland.

David’s father Rinzi, a jolly trekking guide from Phaplu, and his level-headed and kind mother Claudia, a children’s nurse from Innsbruck, both did a perfect job of raising and encouraging him to follow the call of the mountains.

As a climber, he was a wunderkind, discovered at the age of five by Everest-legend Peter Habeler. He mastered his first 5.13b (8a) at age ten. Competing as a young teenager in several classes (lead climbing, bouldering) of the Climbing World Cup series, he became multiple Junior World Champion and, as an adult, won everything there is to win until he got bored with championships.

David, in 2008: “You fly into some faceless Chinese metropolis for a competition in a huge gym, then you fly back home. This way you don’t experience anything. But I want to make experiences.”

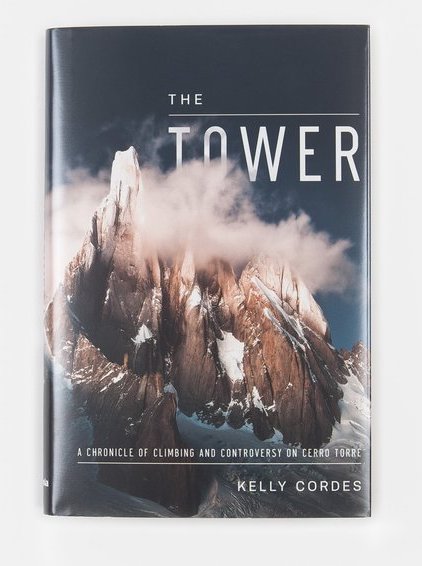

His experiences as a mountaineer opened up new horizons in alpine-style climbing. He established a half dozen difficult routes around the world – from the walls and crags of the Alps to the Baatara Gorge in Lebanon – but he will forever be connected to the history of Cerro Torre in Patagonia, where he freed the infamous Compressor Route, in January 2012, together with fellow Tyrolean Peter Ortner.

Cerro Torre was an immense stepping stone in his life and made his name: the archetype David, taking on a giant Goliath of granite.

In late 2018, he entered the highest echelon of his sport — if you want to call extreme mountaineering a sport: His solo first ascent of Lunag Ri (6907 m) in Nepal, his father’s home country, was a Himalayan masterpiece and won him a 2019 Piolet d’Or. The drone images of his small silhouette balancing along the narrow snout of Lunag Ri’s summit spur went around the world. It seemed like he was stepping out on a bridge to another dimension.

In the Khumbu, he also summited Cholatse and Ama Dablam. In the Karakoram, he repeated the Albert/Güllich route Eternal Flame on Trango Tower and reached the highest point of Chogolisa’s heavenly roof.

Yet, it’s not only the finished projects and summits that are his heritage. It’s his visions and aspirations that showcased a new perspective: Masherbrum’s towering NE Face and the mighty SE Pillar of Annapurna III will be associated with him, although he will not return to these mountains to execute his lines on them. German climbing icon Stefan Glowacz once remarked: “Either David will become the next Reinhold Messner, or he will die.”

xx

“In the right moment, you can’t do anything wrong, and at the wrong moment you can’t do anything right.”

xx

David Lama

xx

Alpinism demands that you put your life on the line. So he became an expert at walking that line and staying alive. For his solo rap-offs on ice walls, he experimented with Abalakov-anchors, V-threads, and self-releasing quick screws.

Like a scientist, he worked on reducing the weight of his equipment and backpack to the barest minimum. He designed ski bindings in which he could click his mountaineering boots, and he had himself smithed extra-light bird beaks, but never considered serializing and commercializing these prototypes.

Still, it wasn’t just on vertical terrain that David Lama was clever and inventive in an idiosyncratic way: he knew how to construct reliable bobbers for fishing, using an empty Red Bull can and some duct tape. His favorite hot beverage on the mountain was melted snow in which he would dissolve a Ricola herbal bonbon.

Photographer Corey Rich recounts how David occasionally was more up-to-date than himself, regarding new camera lenses and photo equipment. Like most of his colleagues and friends, he also remembers how David could flip the switch back and forth between being a juvenile prankster beaming with the simple joy of practical jokes and being a discerning, hyper-responsible athlete.

Three things meant the world to him: adventure, style, and friendship.

I was not friends with David, but I worked with him as an editor on his blog for Red Bull’s Austrian website. Every couple of months between the summer of 2007 and the autumn of 2012, I would call or meet him after competitions in France, Japan, Russia, or China, or later on, on expeditions to Kyrgyzstan, Chile, Argentina, India, and Pakistan. I must have interviewed him at least 30 times.

One of the first occasions I met David in person was at a big party at Hangar-7, in late 2007.

Back then, he was still known as Fuzzy, pronounced ‘footsy’, meaning a scrap of paper, because David had always been the smallest and youngest among his climbing peers. Also being the most ambitious, he outclimbed friends many years older than him. He was a starry-eyed teenager with a wave of black hair falling over the left side of his face, who wanted nothing but the next climb to appear in front of him. The harder, the better.

I wasn’t very keen on indoor sports climbing, and his name only rang a faint Buddhist bell with me. But I remember feeling an immediate affinity with David. Like me, he was from the Tyrol, and he was taciturn; a child of nature who felt most at ease in the wild, away from the madding crowd. The posh party folk didn’t faze him. Still, he was extra kind to everyone he met and shook hands with. Hardly speaking a word, he let his rogue grin do the socializing.

Flash forward ten years, and David Lama was an established mountaineer and a National Geographic Adventurer of the Year. His English had become highly proficient (with a hefty Californian inflection). He was a lot more talkative and media-savvy and had hung out with the preeminent chronicler of Himalayan ascents, Liz Hawley, in Kathmandu.

Little Fuzzy had grown into a well-traveled cosmopolitan and a heartthrob who had starred in an award-winning, feature-length documentary. His million-dollar smile melted hearts like ice.

To top off his credentials, he had gotten blessings from the vertical veterans of Europe and America, Reinhold Messner and Conrad Anker (his climbing partner on a first ascent in Zion National Park and two attempts on Lunag Ri). Both Messner and Anker regarded him as a crown prince of the high-alpine realm.

It felt like he was going to stick around until old age. His rascal energy would simply prevail.

✺

I also remember the phone call to the Cochamó Valley, Chile, in 2008.

David told me that during the past rainy week he had spent time in the refugio (shelter), reading old, weathered climbing magazines. In one of the issues, he said, he had seen a photo of Cerro Torre’s headwall, on which he could make out a free climbable line through a system of flakes and dihedrals.

I searched for an image of the Torre myself and swallowed. My immediate thoughts were: 1) okay, this kid is out of his mind in a megalomaniac way, and 2) he is totally going to pull it off. I only told him my second thought over the phone. It would become the first of many expeditions for David to make the impossible possible.

To keep up with David’s accounts, I spent hours on Google Earth, AAJ, Alpinist, Himalayan Journal, himalaya-info.org, and Wikipedia; on the floor of my study, books on mountains and mountaineering began to pile up like Matterhorns of the mind. I read up on landscapes, peaks, and ranges, as well as on the technical terminology and the history of alpinism.

Mainly through David’s projects, I discovered a fascinating field of knowledge and started tracing a global subculture with its own rules and ethics.

Among my many other obligations at Red Bull Media House, this was one of my dream gigs for me. I looked forward to these calls and getting the lowdown from David, which I would then fashion into a written account in the first person singular and send back to him for authorization.

At the beginning of our working relationship, when he was still competing, it was challenging to get him to speak at all. This arrangement occasionally became a source of amusement for both of us. I found this more endearing than enervating because I know it from myself: When all the words have gone away, there is nothing left to say. But we had to get something of substance out to his fans on the internet. I had to come up with strategies to coax details out of him so that I would eventually end up with more than five sentences on the pages of his blog.

This changed drastically once he shifted his focus to expeditions and wrote his autobiography (at the ripe age of 19). I was surprised by how quickly David matured into a self-reflective raconteur with a keen eye for detail. He always approved my transcripts and was a pleasure to speak with – polite, precise, and generous.

Until one day, when I spoke with him on a crackling phone line after his first expedition to the Karakoram in the late summer of 2012 (see edited interview above). I wasn’t quite present, as I was going through a personal rough time. As a consequence, I presumed that David and his partner Peter Ortner had managed to climb the entirety of Trango Tower’s difficult Eternal Flame route in free climbing style – just like he had done on Cerro Torre a few months earlier – and put it in David’s blog: In the usual first person singular.

I thought I had found additional verification for this on two American climbing websites and assumed that David simply was too understated to emphasize this achievement at great length. Instead of calling the man himself back one more time to clarify, I relied on these ‘insider’ threads, which turned out to be ‘fake news’ avant la lettre. It was that kind of mistake that makes you sit at your desk for two days with your face in your hands.

David was rightfully upset and let me know through his manager Florian Klingler at Red Bull Athletes Special Projects, that he couldn’t recognize his own words. I felt needles of embarrassment pricking my scalp, denied all, and pleaded not guilty, but of course, I was. The blog never went public in its original form, but I had breached David’s trust.

xx

“Success, to me, doesn’t primarily mean reaching the summit, but rather living up to my own expectations.”

David Lama

xx

xx

Falling out of favor with guys as astute as David and Flo felt like an unexpected blow to the solar plexus and left a lasting dent in my professional pride.

Today I think it was my denial, more than the deed, that displeased them. However minimally, or monumentally, one has messed up, taking responsibility for it is the only way forward. David had learned this himself the rocky way on Cerro Torre. He had been through a huge internet shitstorm after his first Patagonia expedition, and now someone in his circle of publicists was claiming feats he never even set out for on Trango Tower as there had been just too much ice and rime in its cracks to consider a free climb (In July 2022, Edu Marín, and later Babsi Zangerl and Jacopo Larcher were the first climbers to repeat the Huber brothers’ 2009-free-ascent of Eternal Flame; ed.).

Realizing my sloppiness, I sincerely apologized. He accepted by email, writing that we shouldn’t make a drama out of it. There would be other mountains to speak about in the future. As I soon found out, not with me. David began ghosting me. I got replaced like a bent biner from his harness.

Knowing that it had been my error, I never held a grudge against David. On the contrary: I admired him even a little more for his pragmatism. Somewhat ruefully, I continued to follow his adventures in alpinism from the sidelines. They were great adventures, filmed, photographed, and documented in guerrilla style, with helmet cameras, small media teams, and drones.

Only 15 months before the fatal Canada trip, David had joined the North Face team. Many people in the small mountain sports tribe around the globe were expecting exciting expeditions and collaborations between David and Jimmy Chin, Renan Ozturk, Brette Harrington, Alex Honnold, Yuji Hirayama, Hilaree Nelson, or Cedar Wright.

Racking up with Hansjörg and Jess to tick off classic routes up frozen faces in the Rockies, like Andromeda Strain on Mt. Andromeda, Nemesis on the Stanley Headwall, and the daunting Howse Peak, was an opportunity to test the North Face’s new Futurelight™ fabric, as well as their latest alpine climbing mitts. I guess that it was also meant as an overture for the trio’s future missions — among them another attempt at Annapurna III’s unclimbed SE Pillar, in the autumn of 2019.

Interview by Desnivel (in English) with David, in July 2018, about Annapurna III, Lunag Ri, instinct, soloing, exploration, and first ascents.

“Mountains are a sacred space that can kill you in a blink,” clarifies athlete and guide Melissa Arnot Reid. American alpinist Mark Twight came up with this apposition: “To regularly deal with risk in the mountains you need to have a substantial amount of luck, but you never know when you’re going to run out of it. It’s like having a bank account for which you never receive any balance sheets.”

Now, David Lama frequently stated that he never included being lucky in his calculations; he only believed in bad luck: “I don’t like to depend on luck. Because that would mean that under normal circumstances you would not manage a tour. But I assume that a tour will be successful under normal conditions. I just must not be unlucky.” Considering the obvious objective hazards of David’s projects, I secretly tried to prepare for bad luck.

One day, the message would come in. Now it has.

I just wish David would have had at least 28 more years to realize his big Himalayan dreams, to start a family with his sweetheart Hadley Hammer, and to grow into an elder statesman of climbing: a mentor, a teacher – a lama. He could have become a worldwide legend of sports like Muhammad Ali. He had it in him. Instead, he became something like the Bruce Lee of climbing: a wandering star that momentarily lights the way, then vanishes.

But mysteriously, his short life seems fulfilled and perfectly rounded. He showed the world who he was and how it’s done. The ‘how’ always being of the highest priority; the climbing ethos ‘by fair means’ always applied to life itself. Despite his youthful demeanor, he had an old soul. Just in case this sounds too hippy-trippy (I’m sure, it would to David’s ears), let’s put it this way: He had wisdom far beyond his years (not that this would make him cringe any less…).

In hindsight, his life and even his exit seem like he had dreamed it up: quick, spectacular, and surrounded by the monumental beauty of mountain wilderness. His last impressions: sky, cloud, rock, snow.

David Lama’s inner calm, his mischievous smile, and his clarity of assessment are sorely missed. His light shines on.

xx

xx

xx

xx

xx

xx

Listen to a conversation with David Lama in a 2018 episode of

xx

The Firn Line xx

xx

✺ ✺ ✺