THE FINDING OF THE PATH

xx

xx

Famous parents are like high mountains. They cast a long shadow.

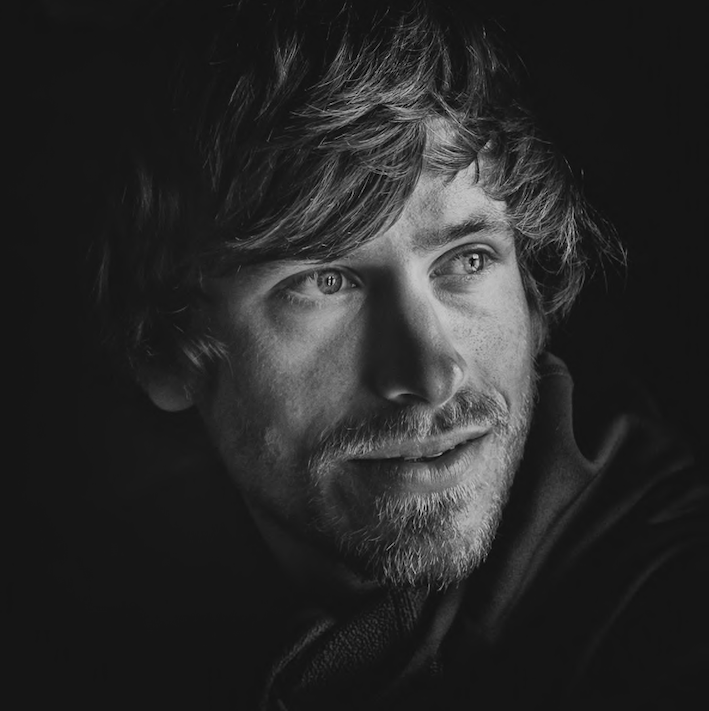

Simon Messner, offspring of a not entirely unknown father (who apparently has done a little bit of mountaineering on the side himself, as we heard), has calmly made his own way into the light.

The thirty-year-old South Tyrolean never really felt like tackling the extreme terrain with which his family name is connected. Too present was the topic of mountains in his childhood.

Nevertheless, in recent years he has investigated the high art of alpinism in his native Dolomites with cleverly selected projects. He has also been increasingly scaling the mountains of Patagonia and Pakistan, as well as sandstone walls in Jordan and Oman.

One thing is certain: Simon, a promoted molecular biologist, does not seek attention, but primarily experiences. At the moment, he just happens to find them in steep ice and desert sand rather than in a sterile laboratory.

Simon has currently leased the “Unterortl” winery entrusted to him below Juval Castle in the valley of Vinschgau, as well as the “Oberortl” mountain farm, to be freer for his travels, adventures, and mountain film projects. And instead of the fatherly castle rock, he moved into a small apartment in Merano where I phoned him just a few days after the beginning of the COVID-19 lockdown, in March 2020.

We talked about his recent projects, his approach to mountain documentation, the calling of vast landscapes, his perspectives on the relationship between man and nature, between civilization and wilderness, and the value of modesty.

*

xx

Simon, you have already repeated many classics in the Alps and especially in the Dolomites and set new accents on well-known mountains and routes with some of your first ascents. What value do you give to the technical difficulties involved when choosing your projects?

I started climbing in the Dolomites, that’s right. How could it be otherwise; these elegant mountains are almost on my doorstep. And I have probably not set any new accents! Rather, I am firmly convinced that the “value” of an ascent cannot be measured solely based on technical difficulty. “How” I do something is at least as valuable – at least for me.

Your two most recent projects took you to Pakistan for the first time. Where were you exactly?

I was in Pakistan for two months last summer. In June, I was traveling as part of a small team: my father Reinhold, my girlfriend Anna, and the two camera operators Günther Göberl and Robert Neumeyer. We circled the Nanga Parbat massif and shot material for a documentary by our production company Messner Mountain Movie. At the end of this trip, I got the chance to first-ascend a six-thousand-meter peak, Toshe III, also known as Geshot Peak.

And in a solo effort too!

It wasn’t planned at all as a solo, it just happened that way. I wanted to do this with Reinhold because he had seen this mountain standing prominently in the southwest, 50 years earlier when he first climbed Nanga Parbat’s Rupal Face in 1970.

Even then, Reinhold and my uncle Günther noticed that the bad weather mostly came from the west – exactly from the Toshe Group. What we didn’t know for a long time and what made the project even more interesting was that the summit was still unclimbed! It was tried three times, but never with success. After climbing it, I also knew why: I have never seen a six-thousand-meter peak as glaciated as the Toshe III. It must be a kind of weather trap.

In any case, there was so much fresh snow on its flanks that we had to refrain from climbing in a party of four – Reinhold, Robert, Günther, and me. But a fast and light solo was possible, and so I was able to climb Toshe III on June 29th.

xx

At the same time, it was an excellent acclimatization tour for your subsequent project, wasn’t it?

Yes, that’s right. I then traveled on by myself from the Nanga Parbat region to the nearby Karakoram range and met my Tyrolean colleagues Martin Sieberer and Philipp Brugger in Skardu. From there the three of us trekked to the Younghusband glacier, a side valley of the upper Baltoro Glacier. Our objective was the 6718 m (22, 040 ft) high Black Tooth, basically a pre-summit of Muztagh Tower.

How did you come across this project in the first place?

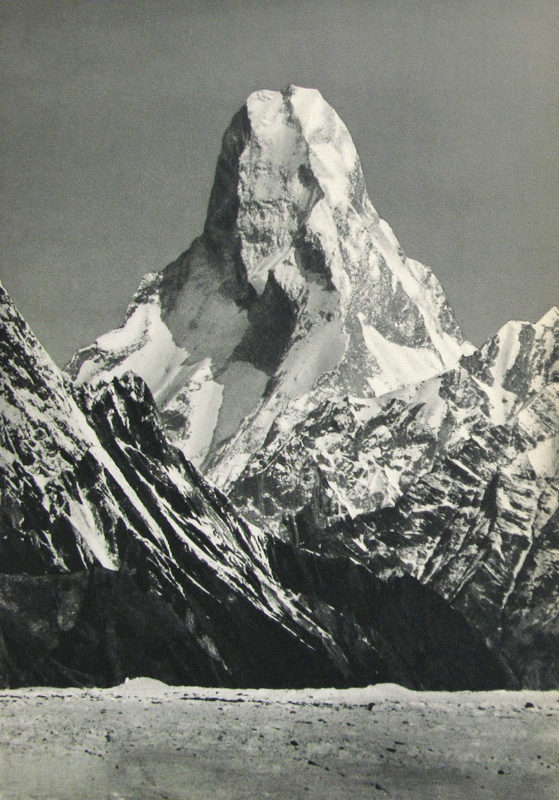

Muztagh Tower, a striking seven-thousand-meter peak, has captivated me since I first saw a photo of it: it is simply an incredibly beautiful mountain! And although it is so distinctive and so easily accessible from the Baltoro, it has only been climbed very rarely (for the first time by a British team in 1956 and a few days later by a French team; note). You could say it remained pretty unnoticed and that alone was reason enough for me to get interested in this mountain.

Eventually, in an issue of the American Alpine Journal, we stumbled upon an article about a failed attempt by two Germans. After a little research, we thought: “We’ll try it!”

xx

As I read on Planet Mountain, you successfully first ascended the Black Tooth. How did your climb go?

In June, when we were still circumnavigating Nanga Parbat, the weather in Pakistan was exceptionally bad and unstable. It snowed or rained almost every day.

Interestingly, in July when we were in the Karakoram, the opposite was the case: it was really beautiful every single day. What we didn’t think about at first was that all the sunshine could bring us potential doom. It was actually too warm to climb a south face. With the heat and the sun rays, ice- and rock-releases thunder down from this large, steep wall. So, now, afterward, I can say that we were lucky! We took a certain risk – I have to admit that.

xx

Were all three of you on the climb?

No, I went up with Martin only. Philipp has never been to higher altitudes and did not feel sufficiently acclimatized, so he stayed at base camp to recover.

The pictures of your climb also show fog. Did it roll in unexpectedly?

On the day of the summit push (July 26th; note), on which (meteorologist) Karl Gabl predicted that the conditions would still be acceptable, the weather tipped earlier than expected. Already in the morning after our second bivy, it started to snow lightly. And then it got exciting because we found ourselves at a kind of dead end. We knew that we could no longer descend or abseil down our ascent route. We had already ruled that out for ourselves.

Why?

Because the ice on the face had become too loose and too fragile to be secured. The screws and anchors simply would not have held. The day before we shouldn’t have climbed this flank – we were both climbing solo because protection just wasn’t possible. Now we certainly didn’t want to go back down this face!

So we were forced to go over the summit and descend into the col between the Black Tooth and Muztagh Tower, which was unknown to us. But with snowfall and thick fog, it became an odyssey, because we didn’t know if we could find a way back down to the glacier from there.

You got into a tricky situation while rappelling, didn’t you?

In several even (laughs). We were already pretty exhausted and we were running out of material. Once we experienced a startling moment when a piton broke out and we almost fell while abseiling. By this time it was already getting dark. Martin had previously almost made an unwanted exit from the wall by a hair’s breadth because he broke both feet through a horizontal ice crack.

We mostly descended in parallel and unroped, so you really shouldn’t allow yourself to make such mistakes! In any case, we arrived at the base of the wall sometime in the night and had no material left except one single Friend. After a short rest, we had to find a way to base camp, because avalanches had destroyed everything around us beyond recognition.

It all sounds extremely, uhm… exciting!

It was, and all the more enriching as an experience – in retrospect. We learned a lot from it. The memory of this tour is still very intense for me.

xx

Your ascent of the Black Tooth seems a bit like a glimpse behind the photographic history of alpinism: Muztagh Tower only appears as a slender spike when seen from the upper Baltoro. But if you look at it from the South, its profile unfolds and presents the mountain as a very steep ridge with several peaks, of which the Black Tooth is the most prominent, right?

Right. Depending on the perspective, Muztagh Tower has very different appearances. The best known, as you say, is that from the so-called Concordia confluence of the upper Baltoro Glacier. This sight fascinated me – as it probably has many mountaineers before me. But when you look at a mountain from multiple angles, its dimensions ideally start to break down. The frontal view of a face is deceptive, often you can’t really assess its steepness.

In general, the Karakoram is an incredibly beautiful range because of the fierce appearance of its mountains! It was my first trip there, but I know I want to come back. The peaks there are – at least for me – the most impressive high mountains I’ve seen so far. They have something very special, something unapproachable.

The Italian photographer, alpinist, and scholar Fosco Maraini once described the Karakoram as “a museum of all possible and impossible mountain shapes”.

That is definitely the case. Whether you climb yourself or not, I can only recommend anyone who has a love for mountains to travel there. The name Karakoram, meaning “black rubble”, says it all. It’s just so wild there: the landscape, the culture, the way people live. I take my hat off to the people who can survive in this harsh area.

xx

Panorama: Guilhem Vellut

Photos have always played a central role in the history of alpinism: Are there historical images that you have memorized as a mountaineer and alpine documentarist?

For sure, and I have a few pictures popping up on my mind right now: First, the photo that shows Hermann Buhl after soloing to the summit of Nanga Parbat in 1953 (taken by Fritz Aumann between camps 3 and 2; note). Buhl looks like he has aged by decades.

Or the pictures of the survivors of the Nanga Parbat expeditions in the 1930s. They fill me both with admiration and terror.

Then the picture Steve House took of his partner Vince Anderson after climbing the Rupal Face in 2005. (The photo shows Anderson kneeling at the summit, his head thrown backward, his arms limp. The photo is an infrared picture, reflecting all the exertion and emotions of the tour; note) These are really good pictures, authentic pictures.

What appeals to me in general in photos or films of alpinism’s history are scenes and moments that are authentic and strong, and that haven’t been manipulated in any way. The viewer immediately recognizes: This is an honest, unposed photo with a strong story behind it – told without words.

How important is this authenticity for you as a maker of historical mountain documentaries?

Concerning our mountain documentaries, Reinhold and I agree that we want to tell the story as close to historical facts as possible. That’s why we shoot as much as possible in the mountains. If it is feasible, also in the original routes, the first ascents of which we want to narrate after all.

We are convinced that the mountain tells the best stories. Half of what you are looking for in the mountains can’t be planned: the weather, the light, the moods.

xx

Photo: Wolfgang Moroder

With your documentaries, you retell strong stories from mountaineering history, but with great persuasiveness, I think. I remember the movie about the first ascent of Sassolungo by Paul Grohmann, which I watched only recently …

… that was one of our first productions ever, yes. A small film shot on a very small budget. For filming, we put three mountain guides in the clothes of the period, giving them the equipment of the 1869 ascent, and letting them repeat the route of the first ascent. We then built the framework of the story around it, so to speak, through reenactments.

What we wanted to say was that the very first phase of change took place already at the very beginning of alpinism – that between conquest alpinism and difficulty alpinism. At that time, mountaineering was assumed by society and wealthy farmers to be futile. A farmer would never have thought of going into the mountains, except maybe to get wood or to find a lost cow.

In addition, it was very firmly anchored in the minds of people that mythical creatures must live up there. Back then, part of the art for alpinists was to sneak around these social taboos.

xx

“We are a wild mess of modern and archaic.”

xx

Are there books from alpine literature that you find particularly exciting and that you may have read more often?

Reinhard Karl (1946 – 1982, German alpinist, photographer, and author; note) I like very, very much. Because he writes so personally, honestly, and directly. Then, of course, Paul Preuss (1886 – 1913, Austrian pioneer of free climbing), which everyone has to read: philosophically brilliant, even then.

Preuss immediately makes me think of Dülfer (Hans Dülfer, 1892 – 1915, German mountaineer and pianist, inventor of the Dülfer seat and first ascendant of many difficult routes in the Kaiser and Rosengarten; note). He was certainly very talented, but unfortunately, he hardly left any tour reports. As a result, he is not remembered as a writer – like many other great alpinists who either did not write or could not write at all.

Not so with Walter Bonatti (1930 – 2011, Italian mountaineer and explorer; note), who was an outstanding personality and left a beautiful book titled The Mountains of My Life. Who else can I think of …

What about Greg Child (* 1957, Australian alpinist, author, and filmmaker)? His books Postcards from the Ledge and Thin Air: Encounters in the Himalaya should be on your wavelength, I assume?

Greg Child, in any case, yes, and Mark Twight of course, (* 1961, American extreme mountaineer) with Kiss or Kill – Confessions of a Serial Climber. Oh yes, Mick Fowler has just published a new book, full of understatement, grit, and black English humor: No Easy Way: The challenging life of the climbing taxman.

There are many climbers who stand out as writers. But I read primarily to develop an overall picture and I read across all times, phases, and stages of development in alpinism. It is essential to understand alpinism as a work in progress and to place its protagonists and their accomplishments within their respective times. It is also essential to be interested in what society was like at that time.

Let’s stay with mountain books, Simon. I just finished reading a book that interested me on several levels. It’s by Robert Macfarlane (* 1976) and it’s called Mountains of the Mind (Granta Publishing, 2003). In it, Macfarlane traces the fascination of mountaineering to its beginnings.

The concept of “deep time”, the geological dimension with which mountains confront us, is also brought up: when people climb mountains, they move, so to speak, in a vertically unfolded view of the Earth’s history. This deep time puts us in a relation that makes us appear tiny, not only in terms of space but also in terms of time. Is that a perspective you can do something with?

Absolutely. It’s an inspiring thought. Time is also a dimension that we humans can hardly understand. A mountain is so much older than we are, so much bigger in that regard. And of course, that also makes us humans questionable, because in a big wall we are, if at all, only ants. We do not belong there. At the same time, I think that is what constitutes a major part of the fascination with mountains: their size, which our minds can’t grasp.

We can try to climb a face to get an idea of its dimensions, but we will never fully understand it. So it is with its dimension in time.

Ultimately, human civilization seems to be just a guest performance in the theatre of the wilderness. Likewise, we were once part of the wilderness that still lives on in us. On the other hand, we go to the wilderness to climb, survive, and persevere in it. What do you think about this conundrum?

The topic of wilderness in man is one of the reasons why I studied biology at all; I specialized in molecular biology, but I also learned a lot about general biology. I’m always looking for answers to these questions.

And it is true: We modern people feel civilized, which we mostly are, but only partially so. Genotypically, a large part of our genes is still primeval and, so to speak, stuck in the Stone Age.

Anyone who believes that we could have adapted genetically to our modern life in only a few hundred thousand years is wrong. Genes mutate at different speeds, but generally rather slowly. This means that a good part of ourselves has remained wild: we are a wild mess of “modern” and “archaic”, and most of our good behavior we probably picked up in childhood.

I am convinced that the life we live in modern societies does not suit us at all. The requirements of civilization do not correspond to the nature of our species.

Even if it may sound strange, feeling certain primal fears is good for us. If you are on the sharp end of the rope in a difficult alpine tour, it is not necessarily “fun”. Fun is something else. You face a primal fear that we can no longer experience in everyday life. Wilderness, and the mountain wilderness, in particular, gives us the opportunity to take ourselves back to another, archaic time.

xx

Photo: Alexander Brus / ServusTV, 2018

In a book by your father Reinhold, I read that there is a conflict between natural law and human law. Do the rules of the civil code disappear after several days of being trapped in a snowstorm in a high camp?

Since I have never had to stick it out in a snowstorm for days, I can only answer this question to a limited extent.

But I think that in a hairy situation, a lot of things will happen naturally. Most of the time the task at hand is not even verbally addressed. When it gets serious, everything is reduced to the basics. Then everyone takes on the role that they can perform best, and the one with the most experience and enough power will always take the lead …

… without actually having to vote on it.

Exactly. It just happens. This gives rise to greater responsibility – also for the partners. You try, perhaps unconsciously, to bundle the energies and then gladly leave the leadership to the other when you feel that he or she can cope with the situation best for everyone. A well-rehearsed climbing party is successful when everyone involved does what they can without having to talk much about it.

xx

“I saw early on that I don’t feel comfortable in public.”

xx

Is it true that you used to suffer from vertigo?

This is actually still the case. Sometimes more, sometimes less. I have only learned to deal with exposure over time. As a teenager, I was horrified of heights. Two meters above the ground – that was the absolute limit for me.

Today I see it this way: It was precisely this fear that triggered my current fascination with mountaineering.

It is a kind of conflict that I still experience: sometimes I am at home, or in any case on firm ground and I really want to go climbing. But as soon as I’m half a pitch up the wall, I just want to get back on safe ground! Most of the time you want what you don’t have. But it’s a little strange in terms of climbing (laughs).

Is it that feeling as if the abyss beneath you is breathing in, beckoning you?

Yes, it’s almost like a vortex. I don’t know if many climbers know this: this oppressive, constricting, throat-tightening fear.

At the beginning of my interest in climbing, I first had to find a way to deal with this discomfort at altitude. Hanspeter Eisendle (South Tyrolean climber and guide; note), who is a good friend, helped me the most, maybe because he understood me best – in his own, subtle way of looking through things. I am very grateful to him for that.

xx

Photo: Simon Messner

Despite this mental challenge, you already have a lot of difficult routes around the world in your tour book and, I think, have made a name for yourself without having to refer to your origins. Is that a difficult balance for you sometimes?

More difficult than I imagined it would be. I’m trying to do a balancing act. I don’t want to be present in the media or any other focus of attention. I saw early on that I don’t feel comfortable in public. On the other hand, I occasionally need a little presence – for example, if I want to do a project in the Himalayas. Otherwise, I could not finance everything myself. But not everyone has to be a professional alpinist, you know.

My godfather, Oswald Ölz (known as “Bulle”, * 1943, Austrian-Swiss physician, mountaineer, and altitude physiologist; note) once said: “The real art is to go mountaineering for yourself.” He meant that it is more liberating to find a way to fund your passion; to have a job for a living, and then to be able to escape into the mountains now and again. That, in my eyes, is the optimum and it would be nice to be able to live according to it. I’m working on it now and in the future.

That makes sense. Because then you don’t have to satisfy sponsors, the media, and the public, just your urge. I don’t assume that there is an 8000er (ultra peak over 26, 246 ft, of which there are 14 in the world) that interests you?

Not really, since there are still so many unclimbed 6000ers and 7000ers, both in Pakistan and in Tibet. But because you ask: I have been doing literary and photographic research on the 8000ers in the past two years, especially for our film productions. As an alpinist, however, I can almost exclude mountains like Everest, Manaslu, or K2 because they are simply too crowded. I don’t want to sit in a base camp with a hundred others.

But if there is an 8000er that would come into question for me, it would be Kangchenjunga (at 8586 m, or 28, 169 ft, the third highest peak on earth, it is located between Nepal and the Indian Sikkim; note).

Why Kangchenjunga?

Because it is less known than others, with a very long approach, and because it is partly still unexplored – especially from Tibet, which is a particularly beautiful and interesting country for me personally.

“To be on the go feels just so incredibly good!”

How important is the development of climbing in Yosemite Valley for you as a mountain documentarist?

Yosemite is of course particularly important for the development of climbing. But less so for the films by Messner Mountain Movies, which are currently more concerned with the beginnings of alpinism.

Then there is the fact that we also lack a bit of a personal connection to the California scene, but of course, there has always been groundbreaking footage coming from Yosemite. Jimmy Chin, as a most recent example, makes great films. The last 20 minutes of Free Solo (An oscar-winning documentary by Jimmy Chin and Chai Vasarhelyi about Alex Honnold’s free solo ascent of El Capitan; note) are awesome. It takes your breath away.

Although I have to say: The Dawn Wall (documentary by Josh Lowell and Peter Mortimer about the first free ascent of the Wall of Early Morning Light by Tommy Caldwell and Kevin Jorgeson, in 2015; note) has almost won me over as a story, in comparison. The documentary really makes Tommy Caldwell tangible as a person.

Photo: Banff Centre/Austin Siadak

What is your highlight of the mountain film genre?

For me, it is still Touching the Void, an older documentary drama about Joe Simpson’s and Simon Yates’s ascent of Siula Grande in Peru. The film (directed by Kevin Macdonald in 2003; note), while simple, is still gripping and very, very authentic. So far I don’t know of any film that tops it.

Let’s take a leap: how important are modesty and contentment for you as an alpinist and in life?

They complement each other. I think I can say that my alpine activities have taught me a lot about humility and modesty.

But what is real humility? Compared to people who live in India or Africa, for example, I’m not humble at all! All of this has to be put in relation. I know exactly what a privileged life we can live here in Europe.

What I learned from mountaineering is that I don’t need much to be content. Anyone who was really thirsty once, or who had to shiver through an ice-cold bivy in which you couldn’t sleep for a second and where the tips of your toes return to life after three weeks can appreciate a warm bed and a glass of water. As simple as that.

At the same time, modesty is also a simple recipe for more contentment. I know it’s easy to say. But it would actually do us all good! Consumption as the meaning of life? Without me. This is neither future-proof nor fulfilling.

Perhaps this is something that we can learn from the current crisis caused by the coronavirus: What our real needs actually are?

I hope so, I sincerely do … Perhaps there is something positive about this crisis if we start rethinking our intentions as a species. I don’t know if we can do that. But if so, this would be THE moment now. I would not only find it beautiful, but it is also high time!

It’s a phenomenon, and maybe you feel the same. We all know, that global warming is a major problem. Still, we just don’t manage to change as a society. We keep pushing this ahead of us. According to the motto: As long as my neighbor is still driving his car, I’ll drive mine too…

Are we a problematic species?

Yes, we are. Highly intelligent in details, but unfortunately extremely ruthless and somehow stupid when it comes to the big picture. Humans, potentially, have the capacity to be very perceptive, but they lack something crucial to understand the climate crisis: its very specific impact on each of us. Man, who lives mainly in artificial cities, can’t yet understand this. It is too abstract.

Maybe humanity only reacts when, like Corona, the problem is right in front of our noses. But when I think about climate issues and pollution, coupled with our lifestyle, it is probably too late anyway.

On principle, I am absolutely against too many rules and laws – there are already far too many of them in Italy! But in order not to pollute our environment, even more, one has to resort to rules and prohibitions. Otherwise, it just won’t work out. That is a sad realization.

xx

“Touareg can travel thousands of miles through the desert, navigating by the stars and the wind drifts. They master skills that we have forgotten in our world. “

Let’s keep our hopes up – before everything changes slowly to a desert. Although deserts also have their charm, don’t they?

Deserts have their own fascination, that’s right. They were always a great passion of mine, even as a child.

The first time I saw the desert was when we accompanied a camel caravan from Agadez to Bilma, crossing the Ténéré, the heart of the Sahara. I did that together with Reinhold. I was only 13 at the time. For a long time, we couldn’t find a tour operator who wouldn’t have claimed that it was irresponsible to do something like this with such a young boy. Finally, we found a couple of Touaregs who agreed to take us on one of their salt caravans. However, they made it clear that they could not take care of us under any circumstances, but they would provide camels for us. In this way, we were self-sufficient and witnessed their lives directly.

In retrospect, it was the trip that left the deepest mark by far.

What is it that fascinates you about the desert?

It’s this vastness. This infinity. Like mountainscapes or high planes, deserts are also difficult to grasp with our senses, they represent another dimension if you will.

Again, I am also fascinated by the life of the people who manage to survive in this harsh environment – from the Mongols of the Gobi to the Touareg in the Sahara. Desert people basically have nothing. The Touareg people (endonym Kel Tamasheq; note) in particular have almost no possessions apart from the clothes they wear on their body and an absolute minimum of equipment. But they can travel thousands of miles through the desert, navigating by the stars and the wind drifts. They master skills that we have almost forgotten in our world. That is very impressive.

xx

But fundamentally, it’s about vastness. Those who travel across a desert have enough time to deal with themselves. You are literally being forced to do so! And of course, I am fascinated by the extreme nature of the desert, which – whether you like it or not – leaves something behind in us.

Is it important to you to cultivate a broad inner horizon?

Certainly. Is there someone who doesn’t want to expand their horizon?

I know, of course, that travel has to be questioned these days. Nevertheless, being on the go feels just so incredibly good, and: you never stop learning! And last but not least because it gives you a different view of your home country. You can see it from the outside. But if we never leave home, we are missing exactly this other perspective.

xx

***

Dieses Interview auf Deutsch lesen

More:

Photo: Simon Messner / Instagram